Colombia has come a long way since the late nineties. When President Andrés Pastrana traveled to Washington in 1999 to strike a partnership with the U.S., the country was close to becoming a failed state, racked by civil war and drug cartels. Funding for the resulting agreement, Plan Colombia, began in 2000, and brought change in the form of improved security and new economic opportunity.

What a difference it has made. This year marks the eighth anniversary of 2016 Colombia’s peace accords with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the country’s largest insurgent group. In December 2021, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that Washington was delisting the FARC as a terrorist organization, as a result of Colombia’s positive peace process. In March 2022, President Biden designated Colombia a major non-NATO ally.

Unlike 1999, today’s Colombia has both institutional will and capacity. Based on this track record, policymakers in Bogotá and Washington might be tempted to continue on the same path as they consider the future of the U.S.-Colombia relationship. But they would be wrong.

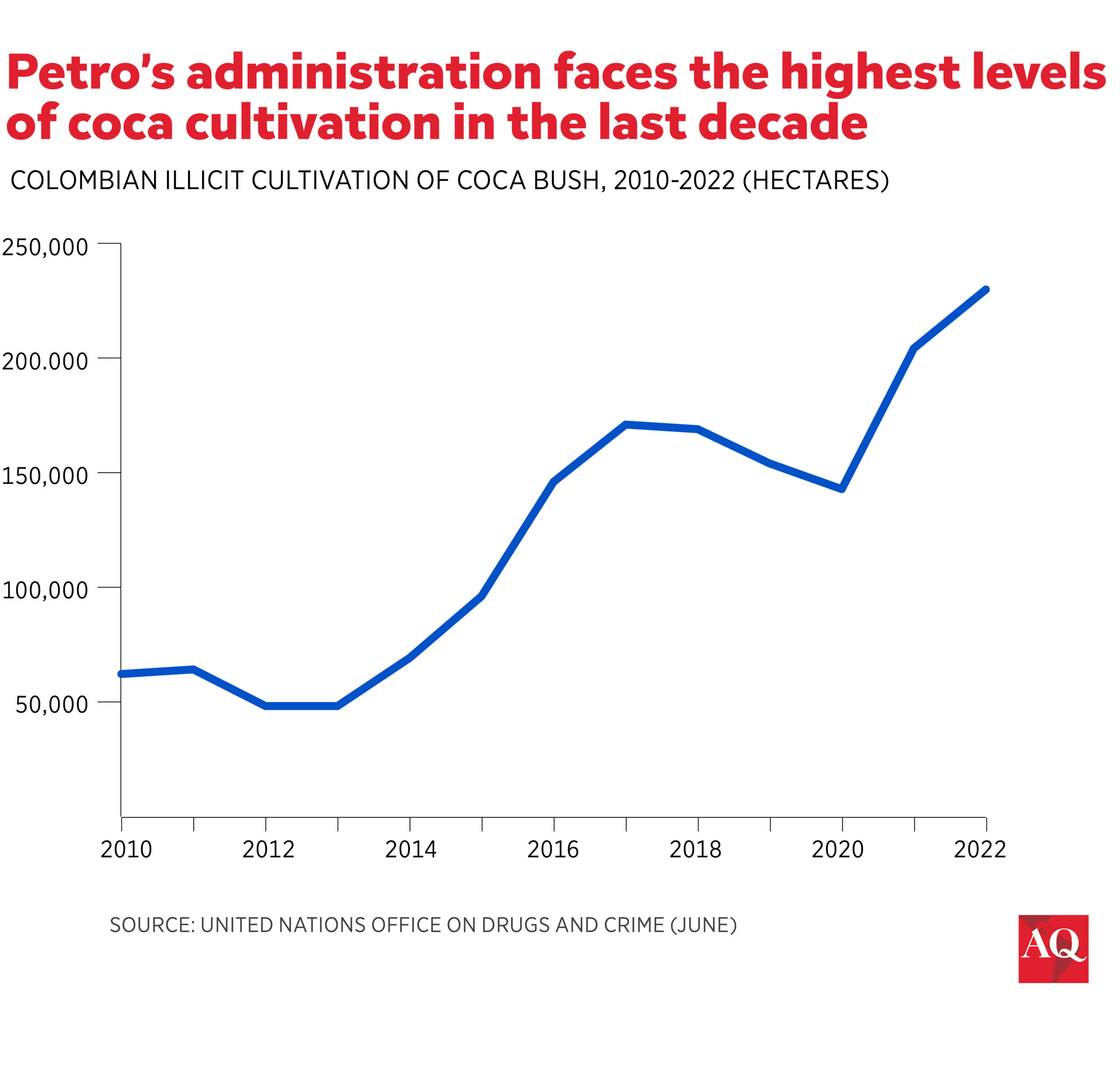

Not all is well in Colombia today. Coca production rose by almost a quarter from 2021 to 2023, violence has worsened in some rural parts of the country where breakaway armed groups are active, and a recent report named the country as the world’s most dangerous for environmental activists.

The old Plan Colombia formula no longer works. To build on what’s been accomplished and prevent retrenchment, a new, holistic approach is needed. Policymakers should focus on extending the reach of the Colombian state, reducing poverty, and providing alternative livelihoods to farmers, ultimately reducing coca production.

Mission drift

Back in 1999, Pastrana’s idea was not to focus on drug trafficking, military aid, or fumigation. Instead, manual eradication of drug crops and economic alternatives for the farmers were supposed to be the emphasis. Pastrana sought to end economic exclusion, inequality and poverty—he wanted peace, and an end to violence.

The original Plan Colombia (written in Washington in English) focused on drug trafficking and strengthening the military. American support in 2000 allocated 78% of funding to the Colombian military and police for counternarcotics and military operations. As a result, Colombia won on the battlefield. But it has yet to address properly the drivers of conflict: income inequality, environmental degradation, organized crime and assaults on Indigenous and Afro-Colombian populations. It risks losing the peace and a descent into criminality and environmental disaster.

The FARC itself may now be delisted, but new organizations have filled the void. Those criminal groups are diverse. Some are very much related to the drug industry, designated by the U.S. as major transnational criminal organizations, and some are on designated terrorist lists. Worse, there are multiple FARC dissident groups still active. There are also the so-called “criminal bands,” like the Clan del Golfo. In certain parts of the country, such as Antioquia, Chocó, Córdoba, and Norte de Santander, young gang members fight for control, oftentimes in urban areas. Organized crime is a mixed bag, but at its core, to a large extent, is competition for control over coca and illegal gold mining networks.

Today, almost all coca production in Colombia comes from the focus areas of the peace accord, the so-called Peace Geography—predominantly rural regions, especially in departments like Cauca, Nariño, and Putumayo.

That, in turn, is fueling violence and criminality across rural Colombia, including threats and homicides against human rights defenders, environmental activists, and social leaders and an increase in massacres, confinement, forced displacement, and youth recruitment into organized crime. Most impacted are the Indigenous communities and Afro-Colombian populations that live in those zones.

Colombia has seen increases in mass displacements and homicides. According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) at least 70 human rights defenders were killed in the country last year. Violence against human rights defenders, environmentalists, and community activists, known collectively in Colombia as social leaders, was a big challenge for President Iván Duque’s government (2018-2022) amid international criticism and demands that it do more to stop the killings, and has remained an issue under Gustavo Petro.

The pandemic exacerbated the situation. Colombia had one of the most restrictive quarantine regimes, but illegal armed groups exploited the lockdowns to exert greater territorial control and access over coca networks and illegal mining, and ultimately, in the process, terrorize communities. Coca cultivation has risen steadily for two decades and is now at record levels, with around 234,000 hectares cultivated in 2022.

The crisis in nearby Venezuela has also added to the problems. Colombia is currently home to over 3 million Venezuelan migrants, plus another 500,000 Colombian returnees from Venezuela. An already strained public healthcare system struggles to absorb these new arrivals, while the government had to reorient much of its security focus to the Venezuelan border, away from coca-growing areas.

Youth are particularly vulnerable now. Extended COVID lockdowns meant schools closed and increased socio-economic pressure on families. There’s fear there has been increased forced recruitment of children.

A better approach

So how can Colombia turn this around? Addressing narcotics concerns is no longer a simple matter of “hectares eradicated,” if it ever was. The metrics used must move toward to something more in line with inclusion and prosperity. A holistic approach is needed on both the Colombian and U.S. sides to extend state presence and security, reduce poverty, preserve the environment—and ultimately reduce coca production.

Rigorous analysis underscores the need for a new strategy. A U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) report on Colombia endorsed a shift toward a holistic approach. A subsequent RAND Corp report also called for much more focus on integrated rural development to integrate public security, counternarcotics efforts, and economic development. These track with the Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission (WHDPC) bipartisan report from December 2020.

Restoring state presence and governance in previously ungoverned areas won’t be easy. But efforts are moving forward, like the territorial development plans for the focus areas of the peace accord, which are advancing at a good pace. These plans were adopted after consultation with local residents who defined their needs for economic reactivation, infrastructure, connectivity, and land formalization. Already, 170 municipalities across sixteen regions have these plans in place.

Twenty-two years into Plan Colombia, with increased levels of coca production, some critics think alternative development has not worked. In fact, the alternative development components of Plan Colombia have been incredibly successful at getting farmers out of coca production despite not receiving the funding the military did. Moreover, alternative development has yet to be tried in the ungoverned spaces where criminal gangs are dominant and where coca is now booming.

U.S.-donated military helicopters in September, 2023.

(Chepa Beltran/Long Visual Press/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Colombia will have to enter the peace geography to really eliminate coca cultivation—a significant commitment under the peace accords—and undercut the financing source of organized crime. Once a state presence is established, a future alternative development strategy for economic inclusion should prioritize agricultural value chains like cacao, coffee, tropical fruits, rubber, and dairy—products proven to create jobs and improve livelihoods.

COVID-19 significantly reduced the Colombian government’s ability to eradicate crops. Three departments, Antioquia, Norte de Santander, and Nariño, collectively showed a 41% increase in coca in 2020 over 2019 figures. Within these areas, three target municipalities—Cáceres, Sardinata, and Tumaco — should be the core of Colombian interventions. Getting the incentives right, extending effective state presence with a holistic response in these three places can create ecosystems for peaceful, sustainable inclusion. That in turn can be expanded as success leads to success.

The land equation

Land conflict was at the core of the civil war. It should now be at the core of a strategy forward. Land market access for the rural poor can promote economic inclusion. Unsurprisingly, titling is also inversely correlated to coca production. Post eradication, if a farmer does not have title to his property, the replanting rate (recidivism) for coca is over 75%. However, where they do have a title, recidivism is under 25%. Bringing citizens into the formal economy translates into more lawful outcomes.

Land titles also open the door to intensification of incentives to get out of coca production. The new “voluntary eradication” system offers farmers titles for their land if they agree to give up coca growing, on the understanding that if they go back to planting coca later, forced eradication will follow.

Making rural land commercially viable means connecting these isolated, rural parts of the country to commercial markets. Illicit markets already have robust linkages for coca and illegal gold mining. Colombia can produce legal, high-quality products at high volume if Colombians have the know-how and connections to the buyers. To this end, tertiary roads are critical to sparking growth in rural Colombia. In parts of rural Colombia with good tertiary roads, there are strong state and private sectors. More often than not, there is coca and violence where there are no good tertiary roads.

The environmental question

Extending state presence can also address climate change and the environment. The same illegal actors that engage in illegal mining and coca production also carry out illegal logging. This is critical not just for Colombia but for the planet. During the war, the FARC controlled many environmentally sensitive parts of the country. As Colombia expands state presence into these areas, its natural resource management will improve. Legal gold sales, sustainable and sanctioned forest management, and alternative forest-friendly crops point the way forward for the Indigenous groups and Afro-Colombian populations who have previously been victims of organized crime.

The peace accords represent Colombia’s best shot at improving citizen security, equity, and stability, advancing the licit economy and inclusion, and reducing coca production. They open the door to democratic participation, investment, and prosperity. And they have worked. Colombia’s security is much better today, and it is no longer the near failed state of thirty years ago. It is not perfect, but it is successful. In that sense, Colombia and the U.S. need to stay that course.

But Plan Colombia is no longer fit for purpose. A new, re-balanced, holistic approach to extend state presence is needed, in line with the “Vida Colombia Strategy” emerging from the last U.S.-Colombia High-Level Dialogue in May, which emphasizes a shared “fight against the global drug problem” as well as an emphasis on rural development. Alternative development that creates jobs and improves incomes for the Indigenous and Afro-Colombian populations, particularly in the ex-conflictive areas, fragile ecosystems, and native lands, will be needed. That approach will advance the peace accords. It will protect forest reserves and the Amazon, placing a high value on human rights and bringing the Colombian people a more sustainable, inclusive economic prosperity and security.