It’s difficult to talk about public safety in Latin America today without talking about El Salvador and its president, Nayib Bukele. In a region where concerns about crime are running high, and organized crime groups are expanding their reach in many places, El Salvador stands out. Under Bukele’s watch, the country’s homicide and extortion rates have tumbled, and whole neighborhoods, once dominated by armed gangs, are now safe for residents to walk around.

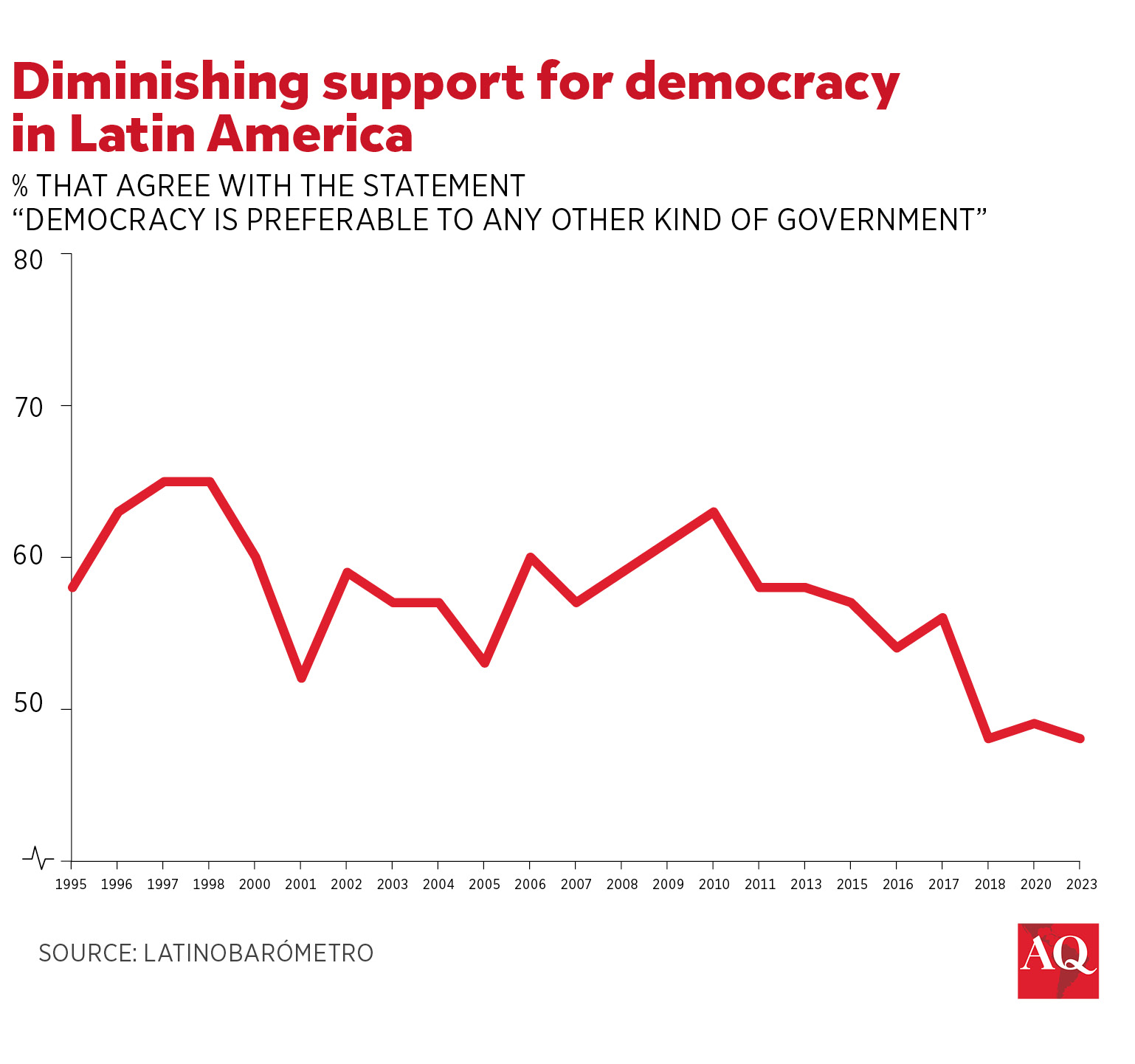

But those results have come at a terrifying cost: tens of thousands imprisoned without due process, a constantly extended state of emergency, and acute concentration of power due to nonexistent checks and balances. Few pause to wonder if the gains against crime are sustainable, or to count up the costs to democracy and civil liberties. And El Salvador isn’t the only case that suggests that when living in fear, Latin American citizens are increasingly willing to sacrifice rights in exchange for safety. The percentage of people in our region willing to accept a non-democratic government if it resolved their problems increased from 46% in 2016 to 51% in 2023, according to Latinobarometro.

As politicians around the region make dubious promises to bring Bukele-style mano dura policies to their home countries, it’s worth asking—is there a workable alternative for Latin America today? Can public security be improved without a massive cost to individual rights?

The answer is a tentative yes. No model is flawless or automatically replicable, but in Guatemala, São Paulo, Brazil, and Bogotá, Colombia, a combination of effective investigation and punishment with social policies aimed at social inclusion has brought tangible results without compromising the rule of law. It’s worth looking at these examples to see how results were achieved.

Guatemala’s progress

Guatemala was among the region’s most violent countries in the early 2010s, but has since seen a progressive reduction in lethal violence. While in 2009 the homicide rate was 45.6 per 100,000, it reached a historic low of 16.7 in 2023—although many issues, such as violence against women and drug trafficking, remain.

The country achieved this through institutional strengthening, increasing training and equipment, and replacing prosecutors’ case-by-case approach with investigations targeting criminal structures. In parallel, the government implemented a social program called “open schools,” extending after-school hours and allowing young people to spend time in a safe environment, limiting their exposure to criminal organizations.

Guatemalan prosecutors and police continued to investigate homicides strategically despite the country’s political divide, the dismantling of the Special Prosecutor’s Office against Impunity (FECI), and the persecution of justice officials who investigated politically sensitive crimes, many of whom were prosecuted or forced into exile.

The case of São Paulo

São Paulo, the largest city in South America, reached a peak of 52.2 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 2000. That rate dropped to 6.1 in 2018 and has remained stable over time, with the 2023 rate being 7.8. Most public policy changes to improve security and reduce homicides started in 1995 and continued through two successive governments by Brazil’s Social Democracy Party (PSD).

One key factor was that the civil police department responsible for investigating homicides where the perpetrator was unknown. In 2001, a plan to investigate homicides by repeat offenders saw the number of incarcerated murderers increase by a factor of seven, and case resolution rates reached 65% in 2005, while the unit responsible for mass murders and multiple homicides achieved a 95% resolution rate in 2003. Authorities invested in information systems to track homicides. That let them better allocate resources and personnel. With around 67% of homicides committed with firearms, other measures focused on confiscating and destroying these weapons. It’s worth noting that while homicides dropped, police lethality remains a concern.

Authorities also implemented social and community programs, like the “Young Apprentice,” which, starting in 2000, provided training for 14- to 17-year-olds from vulnerable backgrounds to prepare them for the labor market and then assigned them a paid job to apply their skills. A community policing model, where officers were tasked with partnering with community groups and non-governmental organizations to diagnose and address security-related problems, began in 1997.

Bogotá’s trajectory

In 2022, the city of Bogotá achieved a homicide rate of 12.8 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, its lowest since 1984. (Though that progress may be slipping: in 2023, the murder rate ticked up by 5.3%.)

The “Mockus and Peñalosa” model, named after former mayors, implemented between 1995 and 2003, focused on alcohol consumption awareness programs and firearm control measures. It also included social assistance for displaced populations and young drug users, as well as rehabilitating degraded areas, following the “broken windows theory” that indicates spaces with visible signs of neglect can incite criminal behavior. Authorities enacted institutional reforms, monitoring and evaluating police conduct and investing significant resources to renew police transportation and communication equipment.

A better alternative for the region

The policies implemented in these areas aren’t perfect. For example, a significant shortcoming in the strategies in both São Paulo and Bogotá is that they do not necessarily target crimes perpetrated by organized crime, an increasing concern in the region, or with firearms obtained illegally.

But they show a path in the right direction—toward an effective security policy grounded in the rule of law. The two crucial ingredients in this regard are an effective criminal enforcement policy with due process to investigate and prosecute those who commit crimes, alongside a social prevention policy to address conditions that drive individuals, especially youth, into delinquency. This combined approach must transcend ideology-based polarization by articulating punitive policies typically promoted by the right and social policies usually proposed by the left.

Given the complexity of addressing structural causes of crime, it is necessary to craft long-lasting security policies, which essentially require some level of consensus among various political players. Due to organized crime’s transnational reach, regional coordination and cooperation are also essential.

A strategic communication policy and sensitivity to the population’s main concerns are also vital. The narrative is shaped by whoever acts first—and currently, that is proponents of mano dura. An alternative strategy must reach broader and more diverse audiences, especially young people. This requires employing new formats, content, platforms, and a different language, appealing to emotions rather than to hard data.

The region needs a democratic leader willing to take on this challenge. Whoever succeeds will be able to address a primary concern—people’s right to security and the state’s obligation to guarantee it—and contribute to curbing democratic backsliding by showing that, for a change, democracy can deliver.