In Mexico, the debate on opening the state oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), to private investment is well under way.

On September 8, as President Enrique Peña Nieto unveiled the government’s budget for 2014, several thousand protesters gathered in the center of Mexico City in front of a massive banner that read “Por Nuestro Presente y Futuro, #YodefiendoElPetról” (“For Our Present and Future, #IDefendTheOil.”) Despite strong advocacy from Peña Nieto and his allies, many Mexicans remain fiercely opposed to allowing foreign oil companies to operate alongside Pemex.

As the debate intensifies, it is important to note one thing: President Peña Nieto does not want to privatize Pemex. Unlike Colombia, which semi-privatized and publicly listed its oil company Ecopetrol, Mexico is merely proposing changes that would make it easier for the state-owned oil company to broker deals with private companies.

In his September 2 State of the Union address, Peña Nieto said, “The opportunity to accelerate our economy is inside of our country—it’s in the decisions that we will make as a nation.” The need for energy reform in Mexico is obvious. And, if Peña Nieto plays his cards right, he should be able to pass the reform.

Problems With Pemex

Peña Nieto is trying to push forward a controversial reform that will fundamentally change the way Pemex operates and allow private-public partnerships for the first time in decades.

Reforms are long overdue: oil production in Mexico has fallen by 25 percent over the last nine years, according to a recent report from the Instituto Mexicano de Competitividad, a Mexico City-based think tank. According to documents that Pemex filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the state-controlled company’s crude oil production in the first six months of 2013 declined by nearly 5 percent. Despite the fact that Mexico has the world’s sixth largest shale gas reserves, according to estimates by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the country has only invested in a handful of shale wells so far. Overall, Mexico has 13.87 billion barrels of proven reserves, the third highest total in Latin America after Venezuela and Brazil.

With access to funding to increase exploration, Pemex itself estimates that it could triple its proven reserves. Left alone, however, it’s likely that Pemex’s fortunes will continue to decline and Mexico could even become a net oil importer by 2020.

After all, Pemex, in its current form, suffers from endemic corruption, hundreds of millions of dollars of losses due to outright theft, a backlog of labor disputes, and concerns about billions of dollars worth of unfunded pension liabilities, as well as serious safety issues.

In a recent interview, Pemex’s 39-year-old CEO, Emilio Lozoya, voiced his frustrations with the current restrictions that ban public-private exploration and production joint ventures, saying, “I believe there are better ways of doing business on behalf of the state.”

Outside observers are skeptical about Pemex’s ability to boost production without better access to foreign technology and capital. Rodrigo Aguilera, a Mexico analyst from the Economist Intelligence Unit, explained that even if Mexico’s government left Pemex with a bigger budget for new investments, “the problem is that it will take years before Pemex becomes technologically capable of exploiting its difficult-to-extract resources.”

“The logic of the reform is that partnerships with foreign oil companies will allow technology sharing so that Pemex can narrow the tech gap,” Aguilera added.

Overcoming Opposition

Although Peña Nieto’s reform package falls far short of the privatization that many foreign investors hoped for, it is still being vehemently opposed by Mexico’s political left.

One of Mexico’s most prominent left-of-center voices, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas—the son of former President Lázaro Cardenas, who nationalized the oil industry 75 years ago—has argued that Mexico should “modernize, not privatize” PEMEX.

The Mexico City office of the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (Democratic Revolutionary Party—PRD), Mexico’s main leftwing coalition, is adorned with a massive banner that says “Who’s leading the defense of our oil? #JoinThePRD.” Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the leftist politician who staged protests after he lost presidential elections in both 2006 and 2012, recently tweeted, “EPN [Enrique Peña Nieto] lied to the people who voted for him. He never said he’d privatize oil.”

In a televised address on August 12, however, Peña Nieto clearly stated the stance advocated by his Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party—PRI): “Pemex will not be sold nor privatized. Pemex will be modernized and strengthened,” he said.

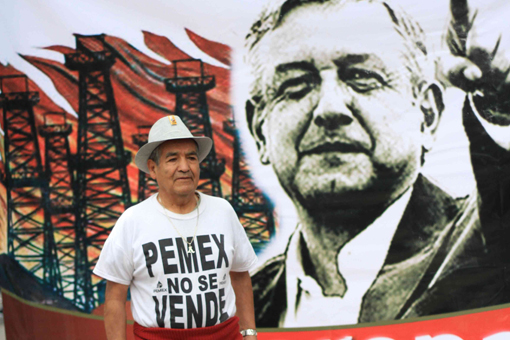

Despite Peña Nieto’s efforts to explain his policy proposal, leftist advocacy groups continue to fight against the “privatization” of Pemex. At the September 8 protest in Mexico City, López Obrador spoke in front of a giant banner that read, “No to the same robbery as always,” and supporters in the crowd wore t-shirts that said, “Pemex is not for sale.”

Strategies for Success

Meanwhile, as activists from the Left look back at Pemex’s long history as a state-owned enterprise, policymakers from the more market-oriented PRI and Partido Acción Nacional (National Action Party—PAN), a right-of-center party, are focusing on maximizing the efficiency and social returns of Mexico’s utilities.

For example, one of Peña Nieto’s first actions as president was to propose a telecom reform that will open up telecommunications to more competition—potentially cutting into Carlos Slim’s and other billionaires’ profits, but also intended to provide Mexicans with better, cheaper and more widespread access to television broadcasts and telephone lines.

They expect that the Pemex reforms will produce similar results by opening the oil sector to more private investment and competition. Perhaps applying his experience reforming the telecom sector, Peña Nieto has chosen not to advocate for the conversion of Pemex from a public monopoly into a private one. The PRI’s focus is on private-public partnerships, and not on privatization.

Still, given the emotional importance many Mexican nationalists place on Pemex, Peña Nieto can still expect vociferous opposition from certain groups. Polling data indicates that although a substantial group of Mexican voters may oppose opening their country’s oil sector to more private investment, information about the energy reform bill has not yet been widely dispersed and absorbed by the general public.

According to a September poll by consulting group Vianovo, only 51 percent of respondents recalled seeing, hearing or reading information about the president’s reform proposal, but 53 percent had a positive view of the PRI’s energy reform ideas. Another poll by the Boston Consulting Group, published August 18 by Mexican newspaper Excelsior, found that 63 percent of respondents were in favor of allowing the entrance of private capital into the oil sector. Meanwhile, an August El Universal/Buendía & Laredo poll indicated that although 62 percent of respondents think Pemex needs reforms to function better, 60 percent of respondents continue to oppose opening Pemex to private investment.

Pemex’s problems are obvious. Peña Nieto and his team just need to work to convince the public that their proposals are the best way to improve the parastatal company. Although some segments of Mexican society will continue to oppose the reform, together, the PRI and the PAN hold 70 percent of the seats in the legislature, and a majority of the state senates as well—enough to pass a constitutional reform.

Senator Jorge Luis Lavalle, a PAN Senator from the state of Campeche, told me, “We’re ready to debate and discuss. A lot of people are against reform because they don’t understand it. But, I’m really optimistic that opposition will fade as we communicate our ideas.”