CARACAS — Some weeks ago, hundreds gathered in the streets of Valera, a small city in the western Venezuelan state of Trujillo, to welcome María Corina Machado, the country’s leading political figure. For days, she had been rallying crowds in the state’s rural towns to support a once little-known former diplomat, Edmundo González Urrutia, who is now the opposition’s candidate for the July 28 presidential election. It was part of an unprecedented campaign in Venezuelan history, after the government banned Machado from running for office.

Like much of Trujillo, the city of Valera has been a Chavista stronghold since the late Hugo Chávez Frías began his Bolivarian Revolution in 1999. But nonetheless, in this rally, even people brought along to government-sponsored countermarches seemed allured by Machado. People in a bus bearing the slogan “Nicolás is hope”—in reference to President Nicolás Maduro, who is running for a third term—started to wave and cheer when they saw her strolling downtown.

Neither was the pro-Machado gesture in Trujillo an isolated event. Days earlier, Machado had led massive rallies in Portuguesa, an agricultural powerhouse and, at one point, the state with the highest per capita share of the Chavista vote. These gatherings illustrate how the political landscape has shifted ahead of Venezuela’s most consequential presidential election in a generation, pitting a dictatorial regime built on Chavismo’s socialist ideas, against a rising and unified opposition seeking a return to democracy.

But there’s reason for caution. “A small part of soft Chavismo feels curiosity, more than sympathy, with what the opposition could offer,” Felix Seijas, director of Caracas-based pollster Delphos, told AQ. “Until now, it doesn’t massively feel attracted [to the opposition], but there’s a part that even voted in the primaries.” Some Chavista areas registered high participation in the primaries held in October 2023, which Machado overwhelmingly won, catapulting her political trajectory to new heights. The recent results build on the 2021 regional elections, which saw Chavismo losing the state of Barinas—Chávez’s birthplace—and dozens of rural municipalities it once controlled.

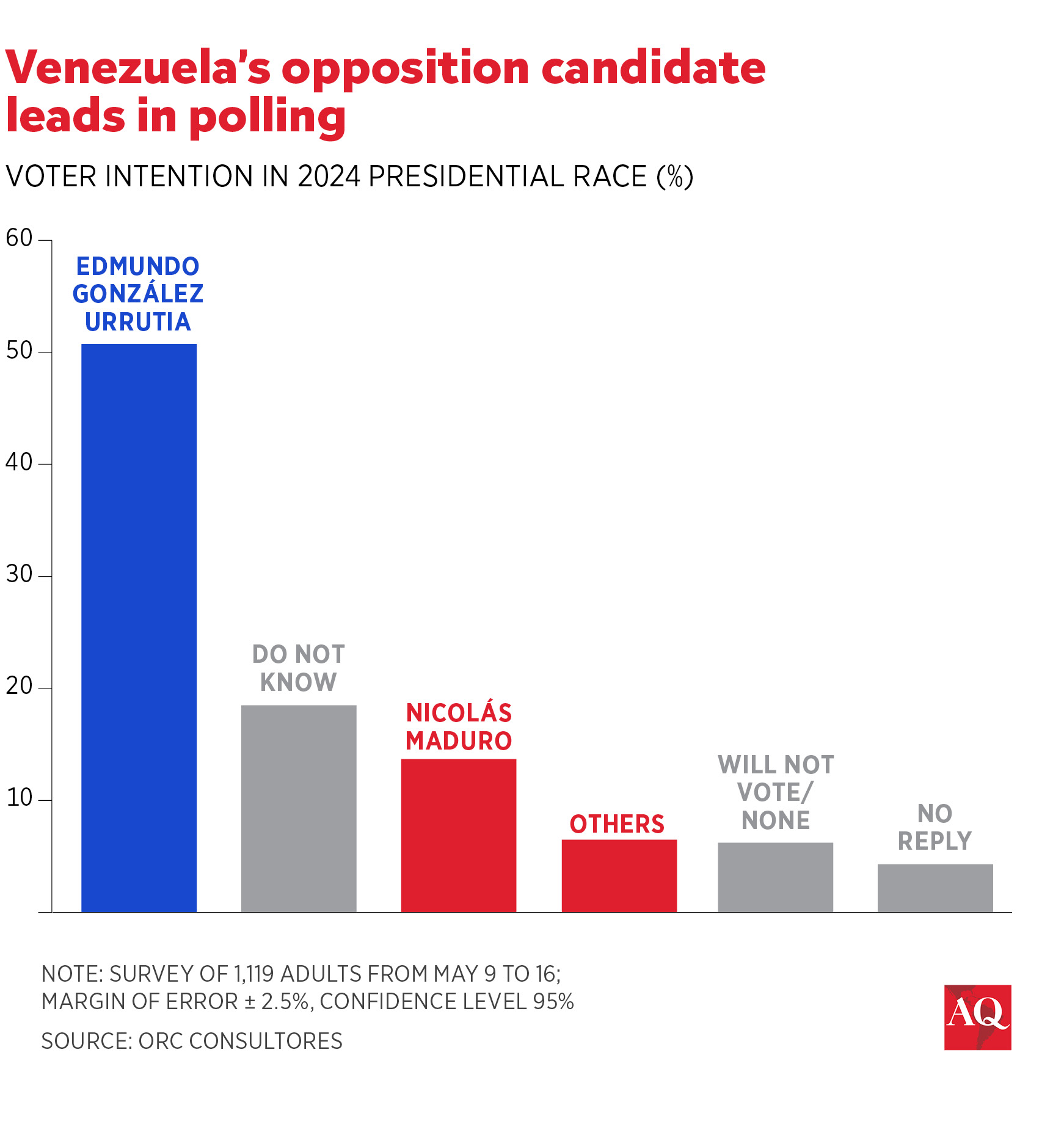

While it’s hard to predict the implications of this change of heart of part of the once hard-core Chavista constituency, its shift may play a significant role in the upcoming presidential contest on July 28, with more than 21 million citizens registered to vote. In recent days, Machado—derided by the Chavista leadership for her pro-market views and her upper-class background—has made a series of public appearances alongside González Urrutia, the candidate who will appear on the ballot, lending flair to a campaign led by a de facto duo. A recent survey by Caracas-based pollster ORC Consultores shows that González Urrutia leads Maduro in voter intention, but with more than 18% of voters undecided.

Along with Machado, prominent political figures from the once-fragmented opposition have been endorsing or appearing in rallies and events with González Urrutia, gaining ground in states that until recently were the strongholds of Venezuela’s dominant United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), primarily rural areas battered by the collapse of the country’s welfare state and public services following an economic contraction of a scale rarely seen in peacetime.

Both in exile and within Venezuela, opposition leaders Henrique Capriles, Leopoldo López, Juan Guaidó, Henry Ramos Allup and Delsa Solórzano have also endorsed González Urrutia. But the coalition has extended beyond the main opposition parties assembled in the Unitary Platform, and his candidacy has also received the support of minor political parties, ranging from democratic socialists and conservatives to Marxist-Leninists and dissident Chavistas. In all, including organizations not recognized by the government and the electoral authority, more than 30 parties have publicly backed his campaign. Yet despite the support González Urrutia’s campaign is garnering, analysts like Mark Feierstein warn that the election’s outcome isn’t a done deal just yet.

Broken promises

For Margarita López Maya, a historian who has studied the country’s left wing, the decline of Chavismo’s popularity in its heartlands has to do with the sources of its base’s loyalty, which she claims are less ideological and more related to the leader’s charisma and the benefits the party’s clientelist circuits could provide.

“What fundamentally moves Chavismo is clientelism,” López Maya told AQ. The well-known political strategy of providing one-off bonuses, food assistance and public employment has been particularly effective for Maduro’s regime. Throughout rural Venezuela, millions of people work in mayorships and regional governments.

Yet, according to Caracas-based consultancy and research firm Ecoanalítica, around 65% of Venezuelans earn less than $100 a month. Inflation—at an annualized rate of nearly 90%—is still among the world’s highest, credit is extremely scarce, the minimum wage remains around $4, and oil production languishes. Venezuela’s stagnant economy, a rump of what it used to be, has fueled González Urrutia’s rise in the polls.

In these systems, people “have no possibility of working and of sustaining themselves through their own means,” explains Mirla Pérez, a researcher at the Alejandro Moreno Center for Popular Research (CEESP), which studies Venezuelan slums and rural areas. For many Venezuelans, Maduro hasn’t delivered the welfare the Bolivarian revolution promised. Facing disenchantment and frustration, core Chavistas are now getting little in the way of social assistance.

Rural and low-income sectors, once bastions of Chavismo, are no longer generating mobilization and enthusiasm. “Machado is collecting the aspirational demands of a better life, related to the material conditions of the middle class,” said Rafael Uzcátegui, a human rights activist who leads the organization Laboratorio de Paz.

Implosion and diaspora

With the old Chavista system imploding, Machado’s message of political change is gaining steam. “It’s an attractive message, of hope, change, alternation,” said López Maya. Seemingly in response to Machado’s rise, Maduro has unveiled blue banners—replacing Chavismo’s characteristic red in exchange for the blue associated with Machado—bearing the slogan “Hope is in the streets.”

Another factor working against Chavismo’s support base and tilting rural and low-income sectors toward González Urrutia and Machado might be the country’s massive migratory crisis, which has resulted in close to eight million Venezuelan living abroad. “Venezuelan culture is very matricentric,” Pérez said, “and migration has broken families,” forcing many to migrate to countries in Latin America and Caribbean, the U.S. and Europe. Meanwhile, she said, for many, Machado evokes the figure of the Venezuelan mother.

Still, the opposition faces steep challenges, ranging from a judicial move that could eliminate its parties from the ballot to the possibility of armed conflict with Guyana over the disputed Essequibo territory that could provide an excuse for the suspension of the elections.

“There’s no tarot cards or magic ball that will tell you what’s going to happen,” said Paola Bautista de Alemán, a political scientist and vice-president of an opposition party. “But you can feel change is in the air.”

Subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify and other platforms