It’s sad but true: Venezuela has become easy for the world to ignore. The South American country’s slow-motion collapse into dictatorship, hunger, and the exodus of almost a fifth of its population has become something of a new normal. Efforts by both the Trump and Biden administrations to threaten or coax the Nicolás Maduro regime to give up power have repeatedly failed. Elections over the past twenty years have been not only unfair but arguably fraudulent.

But there are signs that this time is different. For better or worse, the election scheduled for July 28 will change Venezuela, with outsized implications for the United States and the entire Western Hemisphere. Whether Maduro steals the election outright or allows for a democratic transition, the status quo of recent years will not endure, bringing unpredictable consequences for immigration and regional stability – just as the U.S. election enters its final stretch.

What makes things different now? For the first time since 1998, when Maduro’s predecessor Hugo Chavez came to power, there is a unified Venezuelan opposition based on broad grassroots support, with a single opposition leader: Maria Corina Machado. This is especially surprising since the Maduro government is more repressive than ever and has done everything in its power to suppress dissent: denying the opposition all access to mass media including television, radio, or printed publicity, imprisoning campaign workers, and even denying candidates the ability to stay in hotels when visiting cities around the country. And yet, independent polls show more than 80% support for Marina Corina Machado and mid-teens for Maduro. The difference is big enough that virtually no Venezuelans will believe Maduro if he eventually declares himself the winner. In the past, the margins were always much closer, say 55% to 45%, which made it much easier to get away with rigging an election. That is not the case today.

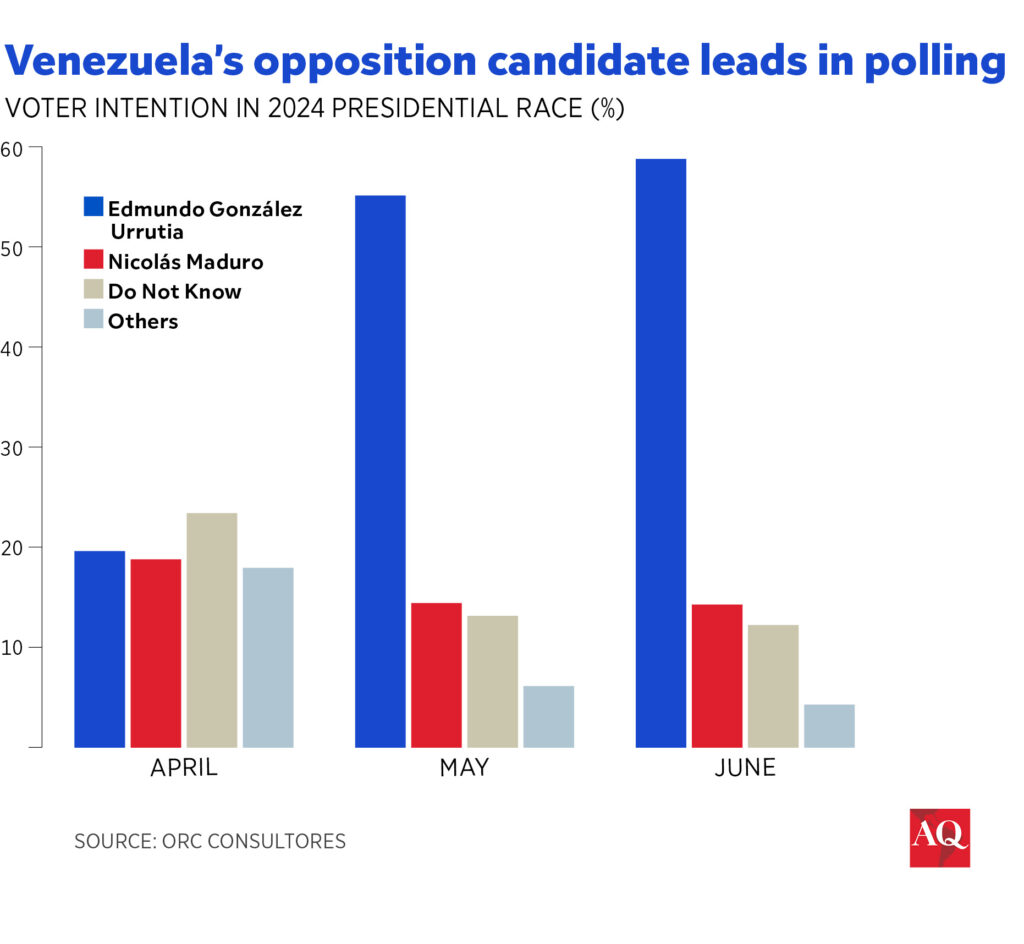

Of course, the Maduro government has not been sitting on its hands. It disqualified Machado on trumped-up charges last year and, in late March, blocked her named successor, Corina Yoris, a respected academic, from running in the contest. Finally, Edmundo González Urrutia, a longtime and retired diplomat, was chosen to run on her behalf. Despite the ban on opposition advertising and media, polls indicate the general public has understood his role, and he is already polling at over 55% and rising.

Meanwhile, Machado has been crisscrossing the country despite the obstacles to getting her message out. Her slogan reaches past partisan politics and goes directly to the hearts of Venezuelan families: “Let’s bring back our sons and daughters.” This reflects the nation’s desire to reverse the exodus of 8 million people, disproportionately young and talented citizens who have sought opportunity elsewhere. Venezuelans are now the second-largest source of undocumented immigrants crossing the U.S. border, after Mexicans.

This has put Maduro and his associates in a difficult situation. The origin of their dilemma lies in the “Barbados Accord” signed in October, in which they agreed to “free and fair” elections in return for a partial lifting of sanctions by the U.S. on the oil industry, mining, and other vital areas. Venezuela was once among the world’s largest oil exporters, but after 25 years of corruption and cronyism, production has fallen from over 3 million barrels per day to less than a million. This decline largely occurred before any U.S. sanctions were applied to its oil sector. The Biden administration restored some of these measures in April but left the door open to some oil production to try to give Maduro incentives to proceed with the election.

Many in Washington and elsewhere in the Americas believed that Maduro, aided by his allies in Cuba and Russia, would outflank the opposition by resorting to manipulation and heavy-handed repression, as they have before. However, the polls and other evidence from the ground suggest the electoral process has already had unexpected consequences and may have at least temporarily escaped their complete control.

A long-awaited transition

Today, it seems unlikely that the Maduro regime will accept the result of the elections and peacefully become an opposition party. Too many tens of billions of dollars have been squirreled away in offshore accounts; too many have been unfairly jailed; too many have been extrajudicially murdered. The worst offenders will fear paying for their crimes or losing their ill-gotten wealth. However, there are reports that others within Chavismo may be interested in negotiating some off-ramp, perhaps exchanging impunity and exile for a democratic transition. They may realize that Venezuela is not North Korea: How far will an army made up of conscripts from popular classes continue to stay loyal to them? They, too, are suffering from the dramatic drop in living standards and a lack of opportunities for a better life.

This all points to why July 28 now looks like an inevitable transition to something else. One option would be a democratic transition. Another possibility, perhaps more likely, is a fraudulent or canceled election that will result in great frustration and anger. That may lead to mass unrest or another massive wave of desperate refugees who have lost all hope. The effects of 2 million to 3 million Venezuelans fleeing their homes would destabilize the entire hemisphere. It would come during the homestretch of the U.S. presidential campaign, in a year when voters say immigration is already the top issue. It would negatively affect neighboring countries and transit points: Colombia, Panama, Mexico and Brazil. For this reason, among others, the leftist presidents of Brazil and Colombia have given at least some support for a real electoral resolution.

That, too, is a sign that governments all over the hemisphere understand the stakes and the fact that some kind of change seems imminent. The White House and members of Congress should continue to push past their fatigue with Venezuela, carefully monitor developments and do everything they can to nudge the country toward a democratic transition. What happens on and after July 28 will likely do more to determine the flow of northward migrants than any border wall.