AQ invited former foreign policy officials from the Trump and Biden administrations to offer their analysis of what another term for their former boss might look like. The articles were finalized in June. To see the Trump essay, click here. | Leer en español | Ler em português

Few elections will impact Latin America and the Caribbean as much as the upcoming contest between Joe Biden and Donald Trump.

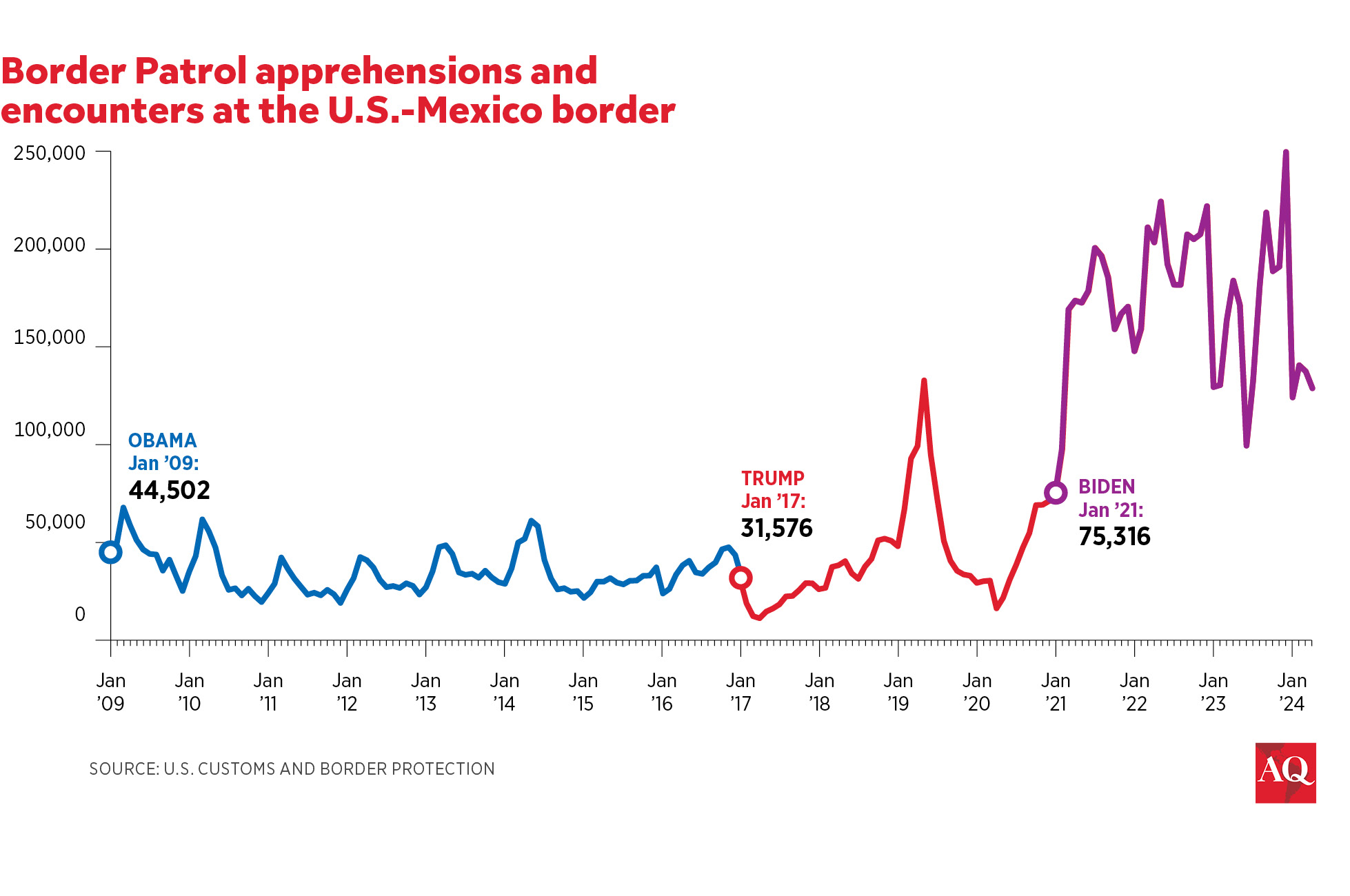

Current trends in the region make the stakes especially high. The region has struggled in recent years with economic stagnation, widespread corruption, misinformation and COVID-19. Those challenges have, in turn, shaken faith in democracy, increased political polarization, and created a historic wave of migration—with 22 million people displaced across the hemisphere (7.7 million from Venezuela alone since 2015).

Amid these challenges, the contrast between Biden and Trump’s policy toward the Americas has been stark. Whereas Trump’s presidency damaged Washington’s standing in the region, Biden has worked to restore U.S. leadership and trust to partner on shared challenges. While Trump empowered populists who preferred a Washington that ignored concerns related to corruption or democracy as long as they claimed to curb migration, or made symbolic (but rarely substantive) gestures to side with him against China, Biden actually defended democracy in Brazil and Guatemala against efforts to overturn the will of voters.

The region has clearly taken note of the difference. According to Gallup polling, a record 58% of people in the Americas disapproved of U.S. leadership after Trump’s first year in office in 2017, a number that remained above 50% throughout Trump’s term. In comparison, regional disapproval dropped to 32% after Biden’s first year in office in 2021 and it has remained below 40% since then. Put simply, soft power matters—and Trump’s transactional foreign policy style undermined Washington’s strategic operating space in the Americas because it weakened regional confidence in the United States as a reliable partner. Worse yet, Trump’s ineffectiveness came at a time when Washington’s global leadership has become increasingly challenged by China. The United States’ foreign policy institutions and frameworks are still adapting to an evolving multipolar order that affords regions like Latin America more opportunities to pick and choose between big powers.

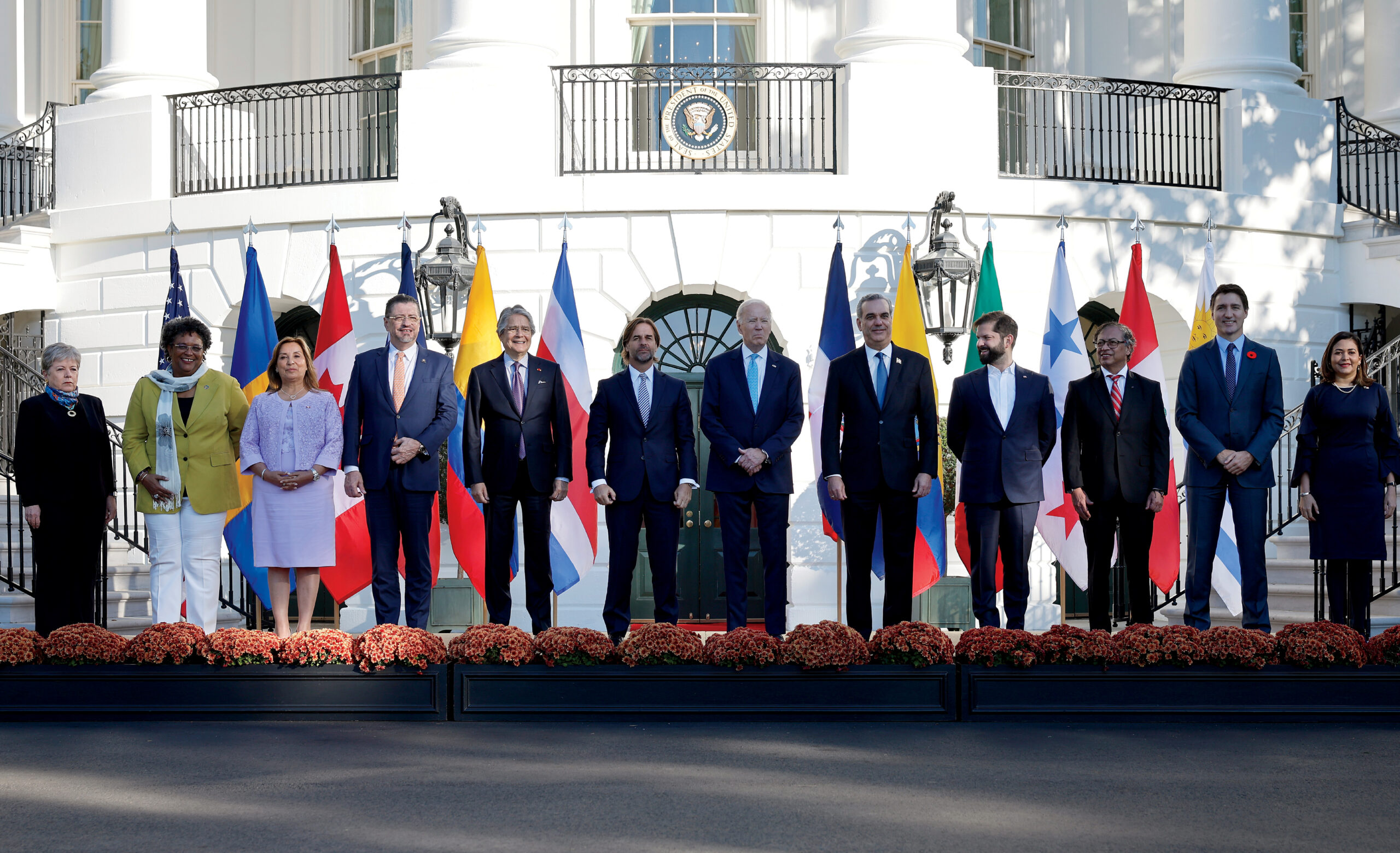

With that context upon taking office, Biden had to first focus on the global pandemic response and historic levels of irregular migration. He did so while also crafting a coherent policy agenda to buttress regional democracy. He also sought to restore trust in U.S. leadership by working in partnership with the region rather than by fiat, including on persistent problems such as promoting a democratic opening in Venezuela and addressing increasingly sophisticated organized crime networks. Biden subsequently launched strategic initiatives that reflect that the Americas feed the world, increasingly fuel the world, and are essential to the clean energy transition that combating climate change requires.

Looking ahead, we should expect Biden to drive an agenda aimed at further capturing strategic opportunities while also investing in efforts to make democracies more resilient and responsive to the aspirations of their citizens. The challenges will not fade, but Biden has laid the groundwork to pursue durable solutions to these challenges with another four years.

The Front-Burner Issues

1. GETTING NORTH AMERICA RIGHT

In a rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape, North American competitiveness is essential to U.S. national security and prosperity. As such, the relationship with the next Mexican government will be central to Biden 2.0’s success. Under President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum’s leadership, Mexico’s governing style will change; the substance of Morena governance probably less so. Migration grabs the headlines, but the most important phenomenon in U.S. relations with Mexico is the deepening integration between our economies. As Washington seeks to de-risk from China and boost domestic investment through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and CHIPS and Science Act, Mexico has become an essential component of the new U.S. industrial policy, as nearshoring has gone from talking point to growing reality.

Biden defended democracy in Brazil and Guatemala against efforts to overturn the will of voters.

This raises the stakes of the 2026 U.S.-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) review, which Biden would approach with care to avoid the uncertainty that surrounded the Trump administration’s grandstanding during initial negotiations. Biden will need to be sensitive to Mexican and Canadian concerns regarding his emphasis on boosting U.S.-origin products, while also seeking compromises with Sheinbaum over Mexican agricultural and energy policies that seemingly violate USMCA regulations and that have understandably concerned the U.S. Congress. Another likely priority for Biden would be closing the transshipment loophole that Trump’s negotiators failed to account for in the original deal, thereby enabling Chinese companies to bypass tariffs by establishing assembly operations in Mexico. China’s role in Mexico’s economy could easily become a lasting source of bilateral friction.

Looking forward, the two countries share increasingly convergent interests on migration, organized crime, and fentanyl—none of which can be addressed by GOP calls for unilateral military actions in Mexico against cartels. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has been a partner on migration, but hypersensitive on organized crime and fentanyl production. Biden will need to evaluate closely how much of that sensitivity transfers to the Sheinbaum team and will need to assess how the recent attacks on Mexico’s democratic institutions could shape the future of this critical partner.

2. REGIONALIZING THE MIGRATION RESPONSE

Mass migration is now an entrenched phenomenon affecting most of the Americas. Though not the primary destination for the 22 million displaced or migrating people of the region, the United States is the country most politically affected by such movements. There are Republican and Democratic federal, state and local leaders around the country who could swiftly agree to support a modernized immigration system that would bring greater order, fairness and security to the process. Unfortunately, there is little hope for even modest immigration reform as long as “replacement theory” and racially infused Trump campaign promises to deport millions outweigh economic needs, rule of law and basic human rights in the minds of GOP legislators.

Without modernized laws, Biden will have to focus on making the broken U.S. immigration system work as well as possible—and look for progress beyond U.S. borders. One potentially far-reaching accomplishment in Biden’s first term was the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection, which enshrined the notion of regional migration as a shared responsibility rather than a contest between source and destination countries. Regional action to update temporary labor programs and promote circular migration would represent valuable progress, especially if accompanied by improved protections against labor abuses. Even more important would be advances in reducing political drivers of migration, such as the crisis in Venezuela.

3. PUTTING OUT FIRES: VENEZUELA AND HAITI

Venezuela remains a powerful drag on regional stability, security and development. It has become a bulwark for organized crime and the largest source of irregular migration in the history of South America, which, in turn, has strained communities and contributed to popular dissatisfaction throughout the region.

Biden inherited a Trump-era “Maximum Pressure” strategy that had failed. While U.S. sanctions were crippling, they were not fatal to Nicolás Maduro and were not used strategically by Trump to begin a viable process to break the political impasse and empower the Venezuelan opposition. Nor was the Trump team’s initial success in winning international support for Juan Guaidó sustainable after the latter lost public support when he proved unable to chip away at Maduro’s power.

Biden recognized the need to use sanctions as negotiating leverage in support of Venezuela’s democratic actors to force Maduro into competitive elections. Biden’s approach supported the emergence of a cohesive Venezuelan opposition determined to box the deeply unpopular Maduro into elections. The Barbados Agreement represented a major turning point, even with Maduro’s efforts to not comply with free elections. Maduro must now either abide by a competitive election or undertake repressive measures no democracy in the region is likely to accept as legitimate.

If the opposition wins, Biden’s focus on regional diplomacy may prove decisive in pushing Maduro to recognize the results. Along with Brazil and Colombia, Biden will play a central role in promoting a forward-looking transition in Venezuela—or in holding Maduro accountable if he seeks to evade the popular will.

The grave situation in Haiti will also continue to demand attention. After months of behind-the-scenes diplomatic efforts to assemble and deploy a UN stabilization force, there is hope that the Kenya-led security mission will reduce gang violence and provide some breathing space amidst a still-fragile political process and skeleton government. As painstaking as Biden’s approach may appear, it reflects a recognition that no solution can be imposed from the outside, while also acknowledging that foreign actors must help enable conditions for a Haitian-led recovery. Trump, in contrast, would almost certainly turn his back on any U.S. effort to address the emergency in Haiti and suspend aid, as he did previously in Central America.

4. RETHINKING ORGANIZED CRIME

The breakdown of order in Ecuador and the expanding reach of criminal organizations underscore the need for an updated strategy for countering organized crime in the Americas. The cartels of the past have morphed into organized multinational businesses with global reach and resilient supply chains. Mexican organizations in particular have taken advantage not only of their penetration of the massive U.S. consumer market, but also of their ties to counterpart organizations throughout the region. South American prison-based gangs are now essential components of these global networks, especially as rival groups vie for control of ports on both coasts to service burgeoning cocaine markets in Europe and Asia. Mass irregular migration provided another important revenue source for criminal groups, both for migrant smugglers and those extorting vulnerable populations.

Increased criminal capacity, revenue and violence heighten citizen frustrations and pose as great a threat to democracy in the region as any authoritarian leader. Biden 2.0 will need to consider a regional response that improves information-sharing and judicial cooperation, while avoiding failed approaches focused on drug interdiction and pursuing high-level targets. More than ever, modern criminal enterprises are businesses and must be confronted accordingly.

Turning Challenges into Strategic Opportunities

1. THE ROLE OF CHINA IN THE AMERICAS

With President Xi Jinping’s aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy and uncompromising economic nationalism ushering in a hardening bipartisan consensus against China in Washington, Beijing’s role in the Americas represents a significant and emblematic challenge for U.S. policymakers. Most of the region neither understands nor sympathizes with Washington’s perspective regarding China. Countries want good relations with both Beijing and Washington and do not want to return to a Cold War dynamic in which the region was valued only insofar as it was relevant to the broader struggle between Washington and Moscow. China is increasingly perceived as delivering the technology and investment needed, as well as already serving as the largest export market for South American commodities. Put simply, countries seek more understanding from Washington regarding how they define their own strategic national interests.

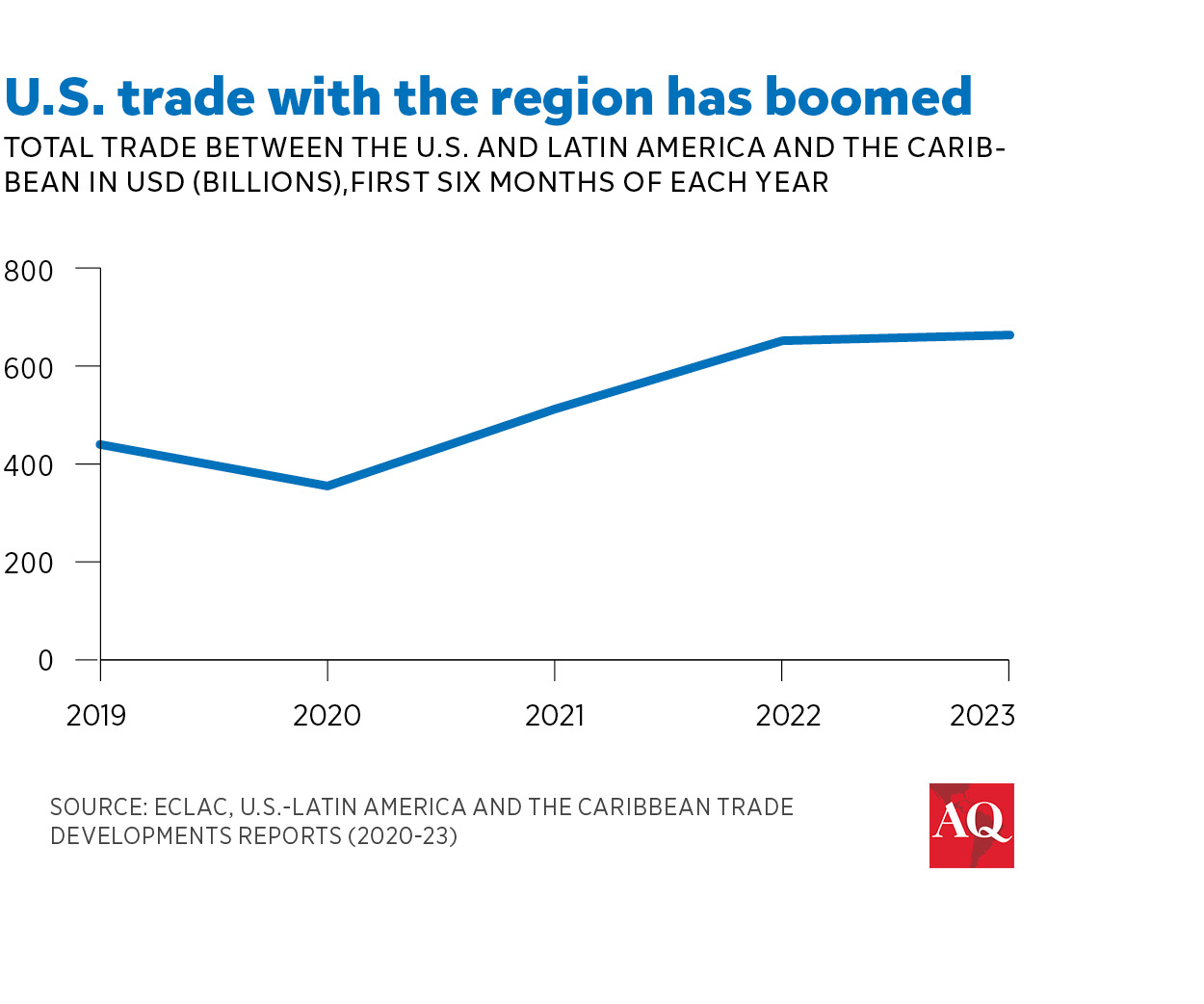

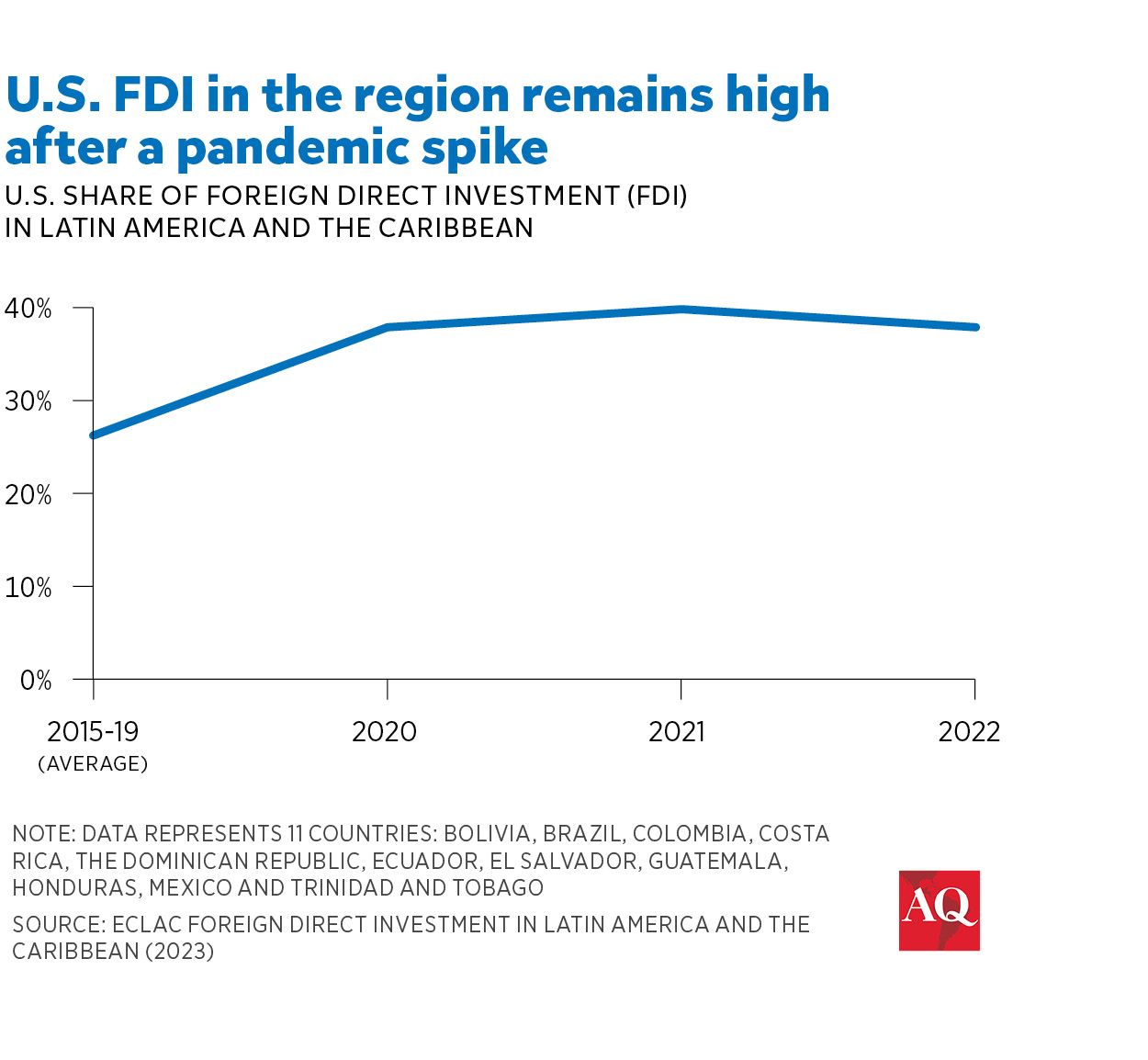

This is why the Trump administration’s “with us or against us” approach to China’s presence in the Americas flopped. Pushing countries to exclude Chinese firms like Huawei without offering other cost-effective options is not a viable approach. Even Trump allies like former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro ultimately refused to preclude Huawei as a government provider out of necessity. These dynamics obscure the fact that the United States remains the largest trading partner and foreign investor for much of the region. But Washington still needs to make a more compelling case that it is the better partner and concretely define its concerns regarding China’s role in the region, including how predatory Chinese policies and state subsidization threaten regional efforts to move up the value chain and away from dependence on commodities exports.

Biden 2.0 must expand efforts to seize economic and commercial opportunity in the Americas.

Biden’s emphasis on unlocking the potential of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and stimulating greater coordination between the DFC and multilateral banks like the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) is a direct response to the need to compete with Chinese investment—especially in infrastructure. Highlights of this emerging policy framework include a DFC-IDB joint investment platform that has identified $3 billion for possible infrastructure projects, a $470 million DFC loan to support small business growth in Brazil, a $30 million DFC investment in a Brazilian nickel and cobalt mine, and a $1.2 billion investment from Intel to expand its semiconductor footprint in Costa Rica that was supported by the CHIPS Act.

2. EXPANDED CRITICAL MINERALS COOPERATION

The Americas is one of the world’s most critical minerals-rich regions. Chile, Peru and Mexico have the second, third and fifth-largest copper reserves, respectively; Argentina, Bolivia and Chile are estimated to have roughly 60% of the global lithium supply; and Canada and Brazil are the fifth and eighth-largest nickel producers in the world, respectively. This makes the region essential to shoring up strategic U.S. supply chains, as well as a vital player in the clean energy transition.

Given the provisions of the IRA and CHIPS Act, Biden has positioned the United States to expand strategic investments and tighten critical minerals supply chains with free trade agreement (FTA) partners like Canada, Central America, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru. The Biden administration should consider going further by using a Minerals Security Partnership-like platform for the Americas to move forward with Argentina and Brazil, which enjoy vast critical minerals reserves and do not have FTAs with Washington. A recent interview by the U.S. ambassador to Brazil foreshadowing the announcement of a purchase of Brazilian critical minerals to support U.S. electrical vehicle and semiconductor production could point the way forward in a second term.

3. PROMOTING COMPETITIVENESS IN CENTRAL AMERICA

Biden’s commitment to provide $4 billion in aid over four years and Vice President Kamala Harris’ efforts to promote private sector investment in Central America reflected the administration’s initial belief that addressing migration push factors in the sub-region would significantly reduce the flow of irregular migration to the U.S. southwest border. Though Central American migration was surpassed in 2021 and 2022 by arrivals from Mexico, Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba, Colombia and Ecuador, a prioritized U.S. commitment to Central America still makes sense given the region’s vulnerability, its proximity to the United States and Mexico, and its potential contributions to regional peace and prosperity.

Biden rightly focused on reducing the constraints to broad-based growth in Central America—such as weak governance, corruption and poor infrastructure—but also emphasized its advantages while pressing for increased investment. These strengths include existing trade agreements with the United States, proximity to North American markets, ample human resources and substantial domestic capital. Biden could help enable growth through a combination of technical assistance and special incentives connecting the region more directly to U.S. supply chains.

Increased trade and investment alone won’t fix long-standing structural problems—Nicaragua’s descent into authoritarianism is proof of that—but the success of Central American diaspora communities is evidence of what they can accomplish in enabling environments. Biden should also be wary of empowering authoritarians in Central America—such as President Nayib Bukele in El Salvador—for perceived short-term gains, and ignoring the lessons learned from such trade-offs in the past.

4. EXPANDING COMMERCIAL & SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION OUTSIDE THE “FTA BOX”

Biden 2.0 must expand efforts to seize economic and commercial opportunity in the Americas. Biden’s centerpiece economic initiative in the Hemisphere—the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity (APEP)—is evolving and could become a foundation for ambitious regional initiatives informed by input from partners, multilateral banks and the private sector. Importantly, it has an open architecture to facilitate growth beyond its initial 12 members, not all of which have FTAs with the United States. The effort is becoming more concrete—focused on fostering resilient supply chains, improving infrastructure and growing regional participation in the semiconductor industry.

To that end, the Biden administration is consulting on a bipartisan basis with Congress to enhance regional competitiveness in cooperation with the IDB and other multilateral banks. For similar reasons, Biden supports the $3.5 billion capital increase for IDB Invest, which will hopefully overcome perplexing opposition by some members of Congress to funding a measure that would enhance private sector participation in regional development. Biden has also worked productively with Congress on the Americas Act by sharing ideas aimed at expanding regional trade. An expanded USMCA might not be the best vehicle for economic integration for the larger region, given the idiosyncrasies of North American trade—and Washington also needs to be careful that the bill’s China messaging does not alienate its partners—but this is a promising effort that shows growing awareness of a clear strategic need.

In a second term, Biden could press for further innovations, such as allowing the DFC to finance projects with any APEP partner regardless of income level, and overcoming the barrier to lending to middle and high-level income countries that limits Washington’s ability to support high-income and well-performing countries like Uruguay. Biden could also work with Congress on sustainable development by moving forward on legislation to contribute to the Amazon Fund.

You Can’t Ignone the “What If”

We cannot write about potential second-term Biden policy in the Americas without touching on the implications of a second Trump term should he win in November; the consequences of such an outcome are simply too profound to ignore. After all, there is little doubt where most of the Americas fits on Trump’s personal spectrum of “nice” versus “shithole” countries.

While many in the region may assume Trump 2.0 would mirror his first term, this fails to account for the (Trump team’s higher level of preparation) and the growing radicalization of his followers and potential cabinet members. The direct effects for the region would be substantial, especially for Central America, which would have to suddenly absorb hundreds of thousands of deportees and the subsequent loss of billions of dollars in remittances. Mexico and Canada would face a far more volatile renegotiation of the USMCA in 2026. And ideological divisions with left-leaning governments in Brazil and Colombia could lead to tariffs and other trade tensions.

Whereas Biden would continue working pragmatically across the political spectrum to support more effective democracies, Trump 2.0 would embolden authoritarian undercurrents already percolating through the hemisphere. Less predictable would be the regional impact of geopolitical instability should Trump proceed with the de facto U.S. withdrawal from NATO and/or back away from security commitments to Taiwan. There could be some regional victors in such scenarios, but a more turbulent global environment, combined with an unstable and inward-looking United States, will not be a winning formula for most.

—

Zúniga is a retired U.S. Foreign Service Officer. In his 30-year State Department career, he served in Mexico, Portugal, Cuba, Spain and Brazil and was National Security Council Senior Director for the Western Hemisphere in the Obama administration.

Zimmerman is a global fellow at the Brazil Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and a senior advisor at WestExec Advisors. He was Senior Policy Advisor to the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and National Security Council Director for Brazil and Southern Cone Affairs in the Obama administration.

Both are founding partners of Dinámica Americas, a consulting firm focused on the Western Hemisphere.