LIMA — Rarely in Peru’s dissonant politics has a measure attracted such bipartisan support as the recent push to scrap parliamentary immunity.

Ahead of January’s special legislative election, almost all political groups, with the notable exception of the severely depleted Fujimoristas, promised to either eliminate or curb the privilege. Polls showed nearly 80% support for abolishing it.

Originally intended to shield lawmakers from politically motivated criminal prosecutions, parliamentary immunity has instead become synonymous with congressional corruption. Time and again, legislators have triggered public fury by using it to avoid or delay justice for apparently well-founded accusations of everything from taking kickbacks to drunkenly groping an airline stewardess.

But six months after that election, the proposed reform’s tortured progress through Congress has sparked yet more political instability, while also shining a light on why so many here view electoral politics with deep cynicism – including Peruvian politicians’ penchant for flagrantly reversing campaign promises once in office.

The latest flashpoint was a series of reforms, passed in Congress by 110 votes to 13, without debate and in a matter of minutes late on July 5. While scrapping immunity, changes to the fine print would in practice have strengthened lawmakers’ protections in various circumstances. The move was a response to President Martín Vizcarra’s proposal to put the matter to a referendum.

Currently, only Congress can lift one of its members’ immunity, something it has frequently refused to do. The new proposal, which as a constitutional reform would need to be approved again by another two-thirds supermajority before the end of the year, would do away with that immunity altogether – with one important exception: Any misdeed carried out in the course of congressional duties would remain safe from prosecution.

That definition would include, for example, influence peddling and demanding or receiving bribes. It could also rule out prosecution for another crime that has been repeatedly unearthed in Peru’s congress, namely lawmakers forcing their official staff to give them a percentage of their wages.

For good measure, and completely out of the blue, Congress also stripped all immunity from the president, judges on the constitutional court and the defensor del pueblo, the official human rights ombudsman.

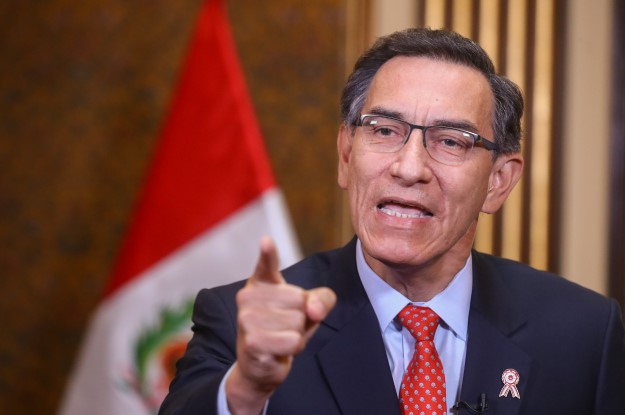

This last detail was apparently a response – a juvenile one, according to its many critics – to Vizcarra’s very public browbeating of a recalcitrant Congress into advancing his reform agenda, which includes barring those with corruption convictions from public office, holding open party primary elections, and having equal numbers of male and female candidates.

The reaction has been uproar. More than a dozen political scientists and lawyers advising the constitutional committee, which had come up with the draft text, quit in protest. The media and public expressed outrage, and constitutional experts warned that the measures violate Peru’s magna carta and will likely be overturned in court.

Vizcarra suggested that lawmakers may have intended to disrupt the process altogether. “They want to mess around with us and for the elimination of immunity to collapse,” he said.

According to Javier de Belaunde, a constitutional lawyer and newspaper columnist, if Congress does not reverse itself the reforms could lead to a crisis of governability.

“If you get rid of these protections for the constitutional court, then you could have those judges dragged into criminal proceedings for their rulings,” De Belaunde told AQ. “It’s very dangerous.”

What remains less clear is why a Congress often accused of populism and electoral calculation would pass such an obviously unpopular measure. Although the new Congress lacks what critics describe as the authoritarian majority of its predecessor, its very fragmentation makes it hard to predict.

Many of its members may be acting on undisclosed economic interests or simply looking to grab headlines, said political scientist Eduardo Dargent. “The mix of diverse interests in play drives a Congress that could be very dangerous,” he warned in a newspaper interview.

De Belaunde adds: “There are also many neophyte members, who are inexpert in constitutional issues, who may have voted without realizing how negative the implications for the country are.”

But the current Congress also has its share of old school politicians, including Omar Chehade, the president of the constitutional committee that drafted the reforms in record time before presenting them to weary lawmakers late at night.

Chehade is best known for his brief stint as one of Ollanta Humala’s vice presidents – and above all for his role in a corruption scandal that forced him to step down from that post and saw his brother serve three years behind bars. At the time, Chehade was also a member of Congress, which narrowly voted to block his prosecution by maintaining his parliamentary immunity.

He is now facing calls to resign while claiming that the legislature as a whole should share the blame for the “misunderstanding.” Congress, meanwhile, is looking increasingly likely to amend its proposal to bring it back into line with what Peruvians actually voted for in January.

Peru’s next general election is scheduled for April, just nine months away. But based on lawmakers’ erratic handling of this emblematic issue, that may feel like a lifetime for those pinning their hopes on Vizcarra turning his reform agenda into real political change.

—

Tegel is an independent journalist and analyst based in Lima. You can follow him on Twitter at @SimeonTegel.