MEXICO CITY— On May 10th, Mexico’s Mother’s Day, hundreds of madres buscadoras marched in cities across the country to demand justice and effective responses from the government on behalf of their disappeared family members. In recent years, what was once one of Mexico’s most popular and festive celebrations has become a painful reminder of the thousands of mothers that have lost their children, either at the hands of organized crime, state security forces, or both.

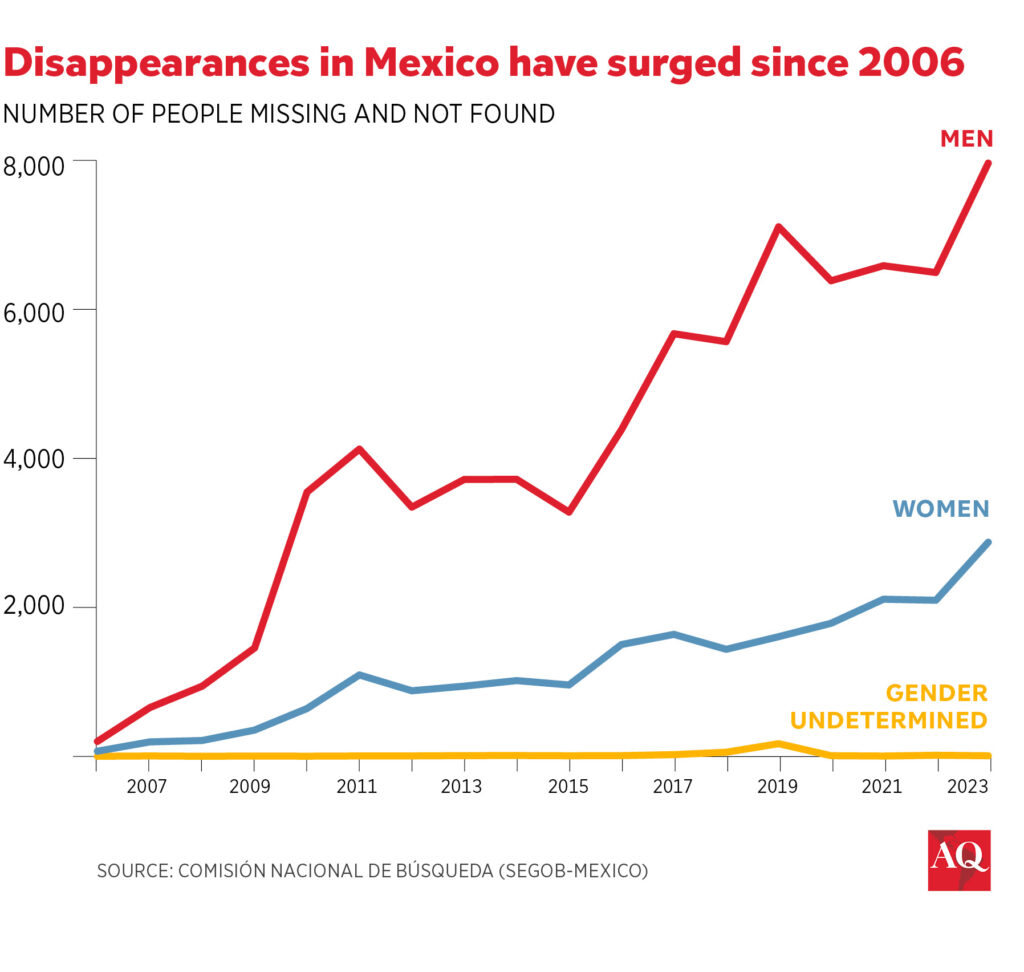

According to official statistics, a total of 114,723 people are disappeared in Mexico. While the data covers cases from 1952 to 2024, the majority have occurred in the last 15 years. And evidence suggests that impunity is the status quo when it comes to missing citizens in this country.

Despite the severity of this tragedy, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) has ignored, discredited, or accused madres buscadoras of overstating the dimensions of this crisis. His government has frequently downplayed the problem by suggesting the numbers are inflated or manipulated by opponents. The disappeared and the mothers who search for them face distrust, polarization, and political conflict, all of which impede citizens’ search for truth and justice.

As candidates prepare to discuss their security proposals in Mexico’s third presidential debate on May 19, the search for the disappeared should be front and center. Rather than presenting it as a partisan issue, the three candidates need to acknowledge the moral urgency this crisis presents and propose specific steps to address the challenges of impunity and criminal violence behind this tragedy.

Searching for the disappeared

According to some scholars, the number of mass graves and forced disappearances in Mexico “has no global parallel.” This crisis did not start with the current government; the number of disappearances skyrocketed during the administration of President Felipe Calderón, who declared an all-out war on the country’s drug trafficking organizations.

Although AMLO’s government initially supported efforts to search for the disappeared—including the creation of the National Search Commission in 2018, which was legislated shortly before his term—over the last three years, the president’s attitudes towards disappearances and the dozens of organizations that search for the disappeared has oscillated between disinterest and open hostility. Since the President assumed office in 2018, the official number of disappearances increased from 53,000 to more than 100,000.

In July 2023, the President announced a revision to the government’s database of the disappeared, and implied that the real numbers are much lower. Last December, the government stated that only 12,377 of the more than 100,000 cases of disappearance were confirmed. In response, activist Cecilia Patricia Flores took to social media, saying: “I wish that the other data was real, and that our pain was a huge lie.”

Being a madre buscadora in Mexico is a dangerous job. Beyond the immediate pain of having lost a child, women face threats and attacks from violent actors who do not want them to investigate these crimes. Mothers have been murdered while searching for their children and loved ones, despite having registered their fears with state authorities.

Despite openly questioning the veracity of data on the disappeared and postponing meetings with victims’ families, AMLO has declared that “no other government has concerned itself with the disappeared like we do now.”

Disappearances as a political hot potato

The issue of disappearances has been a marginal topic in Mexico’s presidential race, perhaps because discussing the crisis is not electorally advantageous for the candidates. When disappearances are mentioned, they are often used to exacerbate political polarization.

Claudia Sheinbaum, the candidate from AMLO’s Morena party, has argued that she will replicate efforts she undertook while serving as the mayor of Mexico City, such as developing databases and consolidating registries based on data from state-level prosecutor’s offices. Referring to madres buscadoras in March, Sheinbaum stated that “it is better to make proposals than to criticize,” a remark that seems out of touch given the collectives’ work locating hundreds of remains, at times using nothing but shovels and picks.

Echoing AMLO’s position, Sheinbaum has also argued that today disappearances are carried out by criminals, and no longer by the state. However, as document by Human Rights Watch, there is ample evidence that the military and police have been responsible for disappearances.

Leading opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez has repeatedly denounced the crisis of the disappeared and has expressed solidarity with madres buscadoras. She announced that she will bring the issue of disappearances back onto the national agenda, and that if elected, she would immediately begin a campaign to identify bodies currently in the Forensic Medicine Services. She also plans to create a fund for the children of both femicide victims and the disappeared.

And yet, she has not publicly acknowledged the direct connection between disappearances and the war on drugs launched under former President Felipe Calderón, who is from the same political party she has represented, PAN. This raises questions about the candidate’s views on the role of the state’s security policies in the ongoing crisis.

Neither of the two main presidential candidates has seriously proposed to move away from the country’s punitive and militarized security strategies, which are at the heart of the issue.

Mexico’s third presidential candidate, Jorge Álvarez Máynez, has stated that he does not want to politicize the cause of the madres buscadoras and that he believes it is more prudent to meet with them after the election. In what could be interpreted as a critique of the current government, he has also said that the issue of forced disappearances “is not resolved by embellishing statistics.”

In his “National Pacification Plan”, Álvarez Máynez promises to create a database of victims and disappeared people with real-time access to detailed information. If elected, he also proposes to reform the National Commission for Human Rights, the Executive Commission for Attention to Victims, and the National Search Commission.

Amidst these muted, vague, or even contradictory proposals, it is madres and victims’ collectives who lose out.

The path to follow

As the candidates prepare for the June 2 election, they should take the crisis of the disappeared seriously and propose concrete steps to tackle the crisis head-on. Mexico’s next president will need to strengthen the country’s forensic capacities, police investigation, and prosecution of these crimes. From Los Pinos, the new leader will also need to rethink Mexico’s overall security strategies to prevent citizens’ further victimization and suffering at the hands of criminal actors, state forces, or both.

Attempts to discredit victims’ appeals for justice represent morally unacceptable obstacles that get in the way of truth and justice. Indeed, as activist Flores said in response to the ‘new’ numbers of disappeared in AMLO’s database: “Perhaps we couldn’t avoid that [our children] were disappeared once, but we will not allow them to be disappeared twice.”