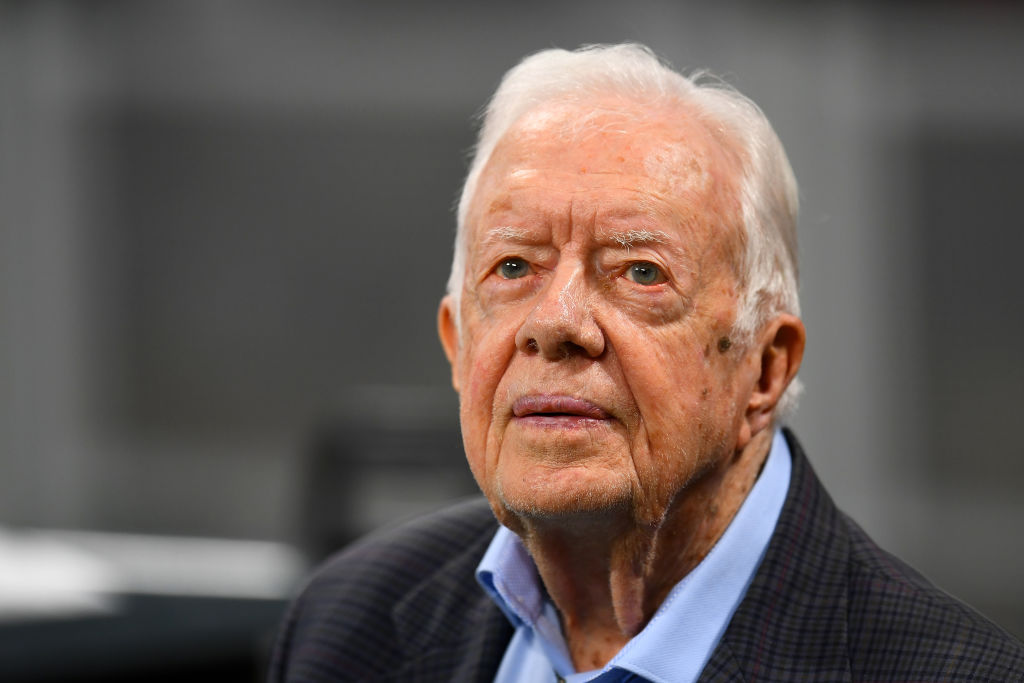

Authoritarian regimes in Central and South America. An unprecedented wave of Cuban and Central American migration. Inflation and resurgent geopolitical tensions. The U.S. president had his work cut out for him from the start—no, not Joe Biden, but Jimmy Carter, president from 1977 to 1981.

Carter’s tenure is synonymous in many minds with an oil price shock, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the 1979 Iran hostage crisis. For critics, he weakened the United States’ position in the world. For sympathizers, he was dealt a bad hand.

But Carter, who entered hospice care in February, transformed U.S. relations with Latin America at the height of the Cold War. He put human rights and democracy at the top of his regional agenda—but shrewdly balanced these concerns with U.S. national security interests. His approach never pleased everyone. Critics from the right accused him of abandoning U.S. allies. Human rights activists within his own administration sometimes lamented he did not press the region’s military regimes hard enough.

But it was exactly Carter’s ability to thread the needle and his skill as a negotiator that accounted for his successes in the Western Hemisphere. You could call his Latin America doctrine “tough engagement.” Today more than ever, it merits a comeback.

In From the Cold

When Carter took office in January 1977, U.S. policy towards Latin America was stuck in a myopic rut—and it was costing Latin Americans their lives. Since the 1950s, presidents had prioritized containing Soviet influence, whatever the cost. Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and Ford kept arms and aid flowing to anti-communist military regimes battling homegrown insurgencies, even as these regimes tore to shreds the political parties, labor unions and student movements that made up the region’s democratic fabric.

Carter’s win signaled a sea change. In his campaign platform and TV debates, he had hammered Ford, his Republican competitor, for failing to condemn the 1973 coup that overthrew Chile’s democratically elected president Salvador Allende. Carter had declared the United States’ “days of unilateral interventionism” to be over and called human rights “a fundamental tenet of our foreign policy.” But he was not oblivious to threats to U.S. national security. Although he had criticized “inordinate fear of communism,” Soviet and Cuban support did prop up insurgencies which, in several cases, had no more interest in seeing the region return to democracy than did the military regimes they combated. Unlike his predecessors and his immediate successor, Carter did not see the region in black and white, but rather shades of grey—a perspective that yielded concrete results in his policies.

Tough Engagement

True to his belief that foreign policy could not be shaped by “rigid moral maxims,” Carter charted a course between lofty idealism and Cold War realism. It rarely made him popular, but it was often wise—and quite often effective. At the height of the Cold War, it would have been easy for Carter to overestimate U.S. influence, act on his deeply held convictions about human rights, and press against abusive regimes using executive power alone. Yet Carter spent his first year in office tirelessly lobbying Congress to pass the 1977 Panama Canal Treaty, which resolved a longstanding grievance shared by many in Latin America and generated an important measure of goodwill for his administration.

And Carter was not afraid to get tough. Tools which have since become standard for pushing back against human rights abuses—like conditions on security and economic aid—were first pioneered by Carter in Latin America. Although Congress set up the framework for conditioning aid, Carter leveraged it to get results. From 1977 to 1979, his administration cut military aid to Latin America from $210 million to $54 million, strategically voted “no” on international financial institutions’ loans, and selectively blocked export-import bank financing.

In the Southern Cone, the strategy bore fruit: according to research by political scientist Kathryn Sikkink, the threat to suspend financing got the Argentine junta to agree to a 1978 visit by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which produced incontrovertible evidence of state-sponsored atrocities. Afterwards, disappearances decreased, and the regime opened some space for political participation. “No” votes on loans to Uruguay fomented “an atmosphere of pressure … to move toward normalization and democracy,” in the words of the economy minister at the time, Alejandro Vegh Villegas, and precipitated the release of thousands of political prisoners. At Carter’s prodding, U.N. human rights machinery and economic sanctions dialed up the pressure on Pinochet. The Rettig commission, formed years later under Patricio Aylwin to investigate human rights crimes, found that state-sponsored killings dropped during Carter’s years, before rebounding under his anti-communist successor, Ronald Reagan. Messaging from the White House was unlikely the only driver behind decreased brutality, but possibly a significant one.

Carter’s approach did not always succeed. In Central America, he ran up against military elites who preferred to forego U.S. support entirely. He took flak from domestic critics for hastening the downfall of Nicaraguan anti-communist dictator Anastasio Somoza before engaging with the revolutionary Sandinista government— the latter’s pivot towards the Soviet and Cuban camp, which Carter tried covertly to stop, largely occurred under Reagan’s watch. Guatemala’s military rulers practically welcomed Carter’s efforts to isolate them, and mounted by far the region’s bloodiest counterinsurgency—no U.S. military support necessary.

Carter’s Legacy

By the 1980 election, the limitations of Carter’s Latin America policy had come into sharp focus, while its successes remained blurry. Carter not only had to contend with the 1980 Mariel Boatlift—a mass migration of 125,000 Cubans and 25,000 Haitians to U.S. shores—and Reagan’s charge that he was soft on communism. He was also heckled by Pinochet in press conferences and branded “Jimmy Castro” by Guatemalan elites. Somoza, before his downfall, had claimed he had more friends on Capitol Hill than did Carter.

Even as his successor, Ronald Reagan, reversed many of Carter’s initiatives—beefing up economic and military support for governments in Central America and the Caribbean with fewer qualms about human rights, and backing the counterrevolutionary Contras in Nicaragua—others long outlasted his presidency. Soft-liners in Uruguay brought back elections. A top Carter administration official, Patt Derian, testified at Argentina’s 1985 trials of ex-junta leaders. Guatemala’s pariah status eventually put pressure on the military to democratize. Reagan administration officials kept pressuring Pinochet to leave power. A U.N. working group on disappearances, founded at Carter’s urging, continued exposing the region’s human rights crimes.

Today, U.S. relations with Latin America are challenging for a different set of reasons than during the Cold War. If, in the past, U.S. presidents sought to stop Soviet and Cuban influence above all else, now the overarching concern is with stopping migration, leading successive presidents to deal once again with anti-democratic regional “partners.” Yet, authoritarian regimes—in Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua—and backsliding democracies, like those of Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala, continue to trample on human rights. Victims and reformers often look to help from the United States, but only sometimes find it.

As Joe Biden and future U.S. presidents look for a path forward in the region, they face a future not unlike Carter once did: the rise of geopolitical competitors, the spread of autocratic regimes and new threats to human rights. Multilateralism, consistent engagement—even with foes—and an ability to thread the needle between competing interests while maintaining a baseline commitment to democracy and human rights might sound like empty platitudes. Carter proved they could be much more than that.