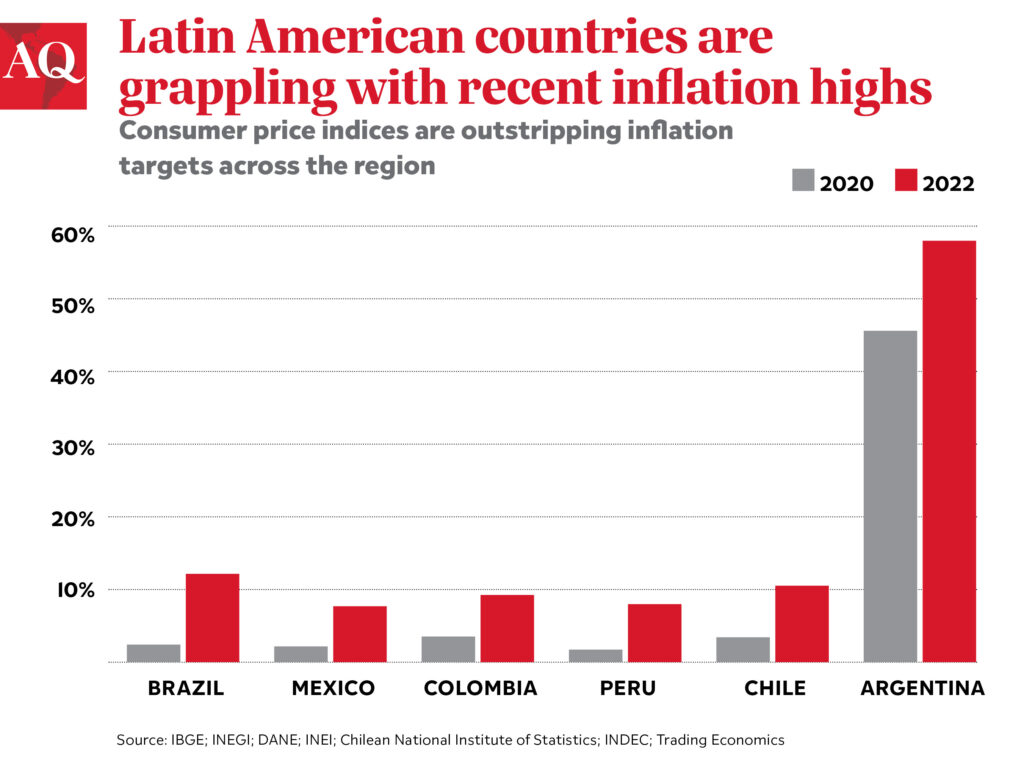

Locals struggling with a spiraling cost of living clashed with tourists in Cusco, Peru last month. Tens of thousands of Argentines took to the Plaza de Mayo on May 12 to demand higher wages as chronically high inflation rose even higher. Even workers at Brazil’s central bank went on strike in early May as inflation has eroded the value of their salaries.

The region—like the rest of the world—is dealing with the effects of twin shocks from the pandemic and the war in Ukraine on energy and commodity markets.

The fact that many countries in the region are energy producers and commodity exporters hasn’t been enough to stop price hikes from hitting the poorest hardest. In Brazil, one of the world’s largest food producers, a basic basket of food goods measured in March was up over 21% year-on-year.

But inflation isn’t just on the supply side anymore: it looks increasingly incorporated into the wider economy across the region, spurring central banks to hike rates at the risk of taking a toll on growth. Meanwhile, lockdowns in China and tightening policy at the Fed are causing some observers to worry about a global recession.

Could hiking rates hurt investment in the months ahead? “The cost of funding is an important variable, but it is not the only one,” Otaviano Canuto, senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, told AQ. “Having inflation out of control would also negatively affect the perception of risk by investors. Just ask Argentina.”

The price spiral is also happening amid a polarized political scenario that is playing a major role in policy decisions.

In countries with chronic inflation, taming it can win elections, said Andrés Malamud, a research fellow at the University of Lisbon. “But inflation will not make you lose.”

More than overall inflation, Malamud said, price increases in sensitive areas such as public transportation could set off the type of widespread protests seen in Chile in 2019 or Brazil in 2013.

So how are the region’s major economies handling the crisis?

Mexico counts on fuel subsidies and the bully pulpit

In Mexico, overall annual inflation reached 7.7% by April, the country’s highest level in over two decades. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s anti-inflation package included voluntary commitments by major companies to raise food production and keep prices steady through the end of the year.

“It may actually help,” Moody’s analyst Renzo Merino told AQ. “But there’s probably not as large of an impact as on the fuel front.”

The country is also subsidizing fuel costs for Mexicans, taking a fiscal hit in doing so—though one largely compensated by elevated fuel prices. Overall inflation could be as much as two percentage points higher without fuel subsidies, according to Merino. Meanwhile, the central bank has already raised its baseline interest rate eight times in a row, reaching 7% on May 12.

High inflation in Colombia could be even higher

Inflation in Colombia shot up to 9.2% in April, the highest level since 2001—surprising many observers who expected slower increases. The country’s central bank has raised interest rates at a steady clip, reaching 6% as of April 29. Food prices have seen especially steep increases, at 20% year-on-year, but are expected to stabilize beginning this month due to base effect changes, said Merino.

But like in Mexico, overall inflation has been reduced by the government’s efforts to control fuel price increases. That policy deepened the national gas subsidy fund deficit to nearly $9 billion as of April, a steep and potentially unsustainable cost. Going forward, the country’s response to inflation will likely depend on the outcome of presidential elections, with the first round approaching on May 29.

Bigger problems in Argentina

Argentina is in a category of its own. Inflation was already running at 50% annually in 2021 before the fresh external shocks this year. In April it hit 58%, and looks set to reach at least 70% in 2022, Marina dal Poggetto, executive director of Eco Go Consultants, told AQ. Transportation is heavily subsidized already in Argentina, and the central bank increased interest rates by two percentage points to 49% in May, still below inflation.

There’s no sign that inflation will calm down even after external pressures abate. Much of the population is inured to chronic inflation, while the policy choice of controlling prices and the exchange rate doesn’t seem to be helping curb the inflationary trend.

“We need a shock program, but the government decided not to do that,” said dal Poggetto.

Tough choices for Chile

Inflation running over 10% is contributing to President Gabriel Boric’s sinking approval ratings, which fell to 35% in early May. In the same poll, 86% said the economy was stagnant or worsening.

The government has increased the minimum wage—just approved by Congress—and injected $40 million into a gas subsidy fund to ease the pain for citizens. The country’s central bank unleashed a 1.25 percentage-point rate hike in early May—up to 8.25%.

Risk of inflationary inertia in Brazil

Amid a fiery electoral campaign, Brazil’s central bank has raised rates by nearly 11 percentage points since March 2021, up to 12.75% as of May 4, while inflation notched 12.13% in April led by food and transportation costs.

President Jair Bolsonaro has complained about the national oil company Petrobras, and has changed leadership at the company twice. But despite being the company’s largest shareholder, the Brazilian government has less control over fuel prices than those of Mexico or Colombia.

Meanwhile, one legacy of the country’s past hyperinflation is that many contracts across the economy, from rent to health insurance, have inflation adjustments built in, meaning inflation can be much harder to lower. “The higher the inflation this year, the more inertial inflation you can expect for 2023,” said Adriana Dupita, an economist for Bloomberg Economics.

Anti-inflation tools in Peru have little effectiveness

Peru’s central bank is duly raising interest rates—up to 5% in May, well behind inflation, which was running at 8% as of April. To ease the burden on citizens, Pedro Castillo’s government has cut taxes on food and fuel, and raised the minimum wage by 10% in early April.

But according to Hugo Ñopo, lead researcher at Group for the Analysis of Development, in an informal economy these tactics have limited effectiveness for many Peruvians.

“That tax reduction has not been translated into final prices, which are still moving up,” Ñopo told AQ. Meanwhile, a lack of financial inclusion limits the social impact of rate hikes. With few tools available to policymakers, a weak Castillo government and popular discontent that preexists the latest crisis, the situation in Peru looks set to remain volatile for months to come.