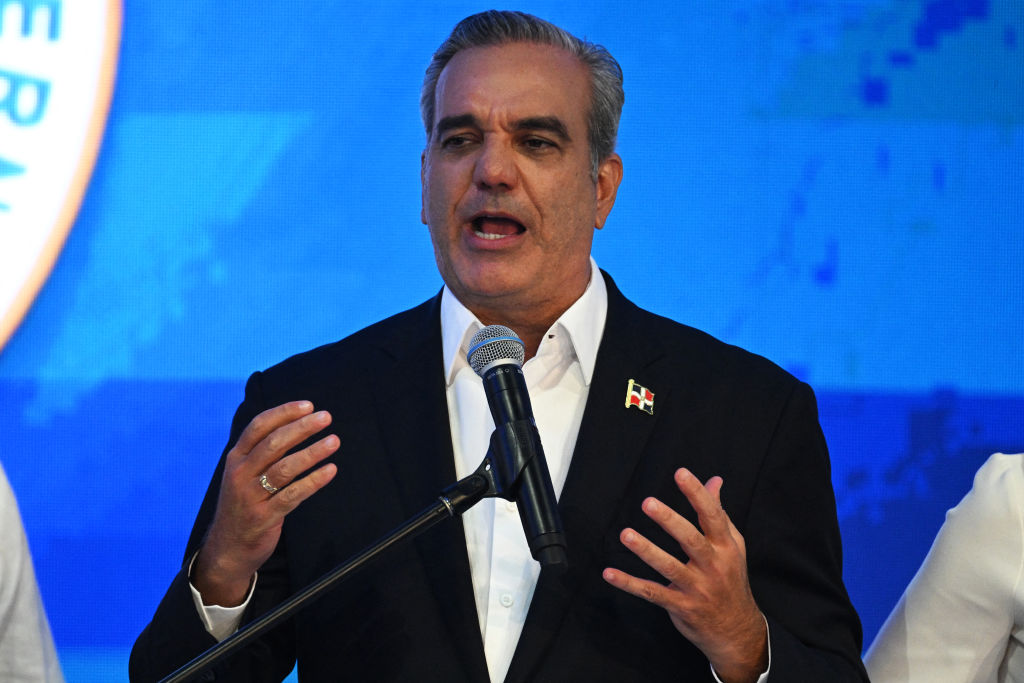

This Sunday, Dominican President Luis Abinader cruised to reelection after winning a preliminary 58.85% of the votes.

Given the recent political history of the country, where the last three presidents have each been reelected across two decades of broad political stability, the result is not so surprising. The question now is how Abinader will choose to spend his renewed political capital: Will he tackle constitutional or fiscal reform or seek to shore up the nation’s struggling public services?

In the past, Abinader has advocated for a constitutional reform entrenching the independence of the attorney general’s office. However, opening the process of constitutional reform might bring the temptation to push for further-reaching changes, including rules around presidential reelection. Abinader has maintained publicly that he will not seek changes to the current two-term limit, but there’s a precedent in the Dominican Republic for pressing for this type of change: the three past presidents—Hipólito Mejía, Leonel Fernández and Danilo Medina—modified the constitution to accommodate their desire to run again.

Fiscal reform to shore up the government’s revenue-generating capacity has been discussed for years, as the government runs a deficit every year between 3% to 5% of the National Budget. Abinader himself said during the campaign that whoever won the election would have to do a fiscal reform. But raising taxes will not be popular.

Another major issue concerns abortion, which is currently banned in the Dominican Republic in all circumstances. For the past two decades there have been attempts, none so far successful, to allow exceptions to save the mother’s life, in cases of rape or incest, or in case of malformation incompatible with life. Abinader supported these changes during his 2020 campaign but made no effort to pursue a change to the existing law, as he courted conservatives, such as Catholic and evangelical groups.

Meanwhile, the country’s public services, from education and health to housing and transportation, need improvements. And, given that Abinader rose to power by harnessing a groundswell of anti-corruption sentiment, keeping at bay allegations of corruption for his own government will be an important task for the Modern Revolutionary Party (PRM). Corruption scandals are more likely to appear during a second term when government officials are tempted to take a laxer attitude toward codes of conduct.

Finally, during this second term, the PRM will have to choose a successor to compete for the next presidential elections in 2028, and the party may have to face the challenge of internal infighting that has affected other Dominican parties in recent years. Abinader is likely to play a key role in the selection process.

How Abinader got here

Abinader’s rise has taken place in line with a few broad trends in Dominican politics in recent years. Ever since the 1970s, when elections in the Dominican Republic weren’t fair, the country has tended to reelect its presidents. But for the last two decades, the breakdown of the two-party system has tended to facilitate the cycling through of dominant parties that, once in power, tend to stay there for a while. The Dominican Liberation Party (PLD) ruled for 16 years until 2020, when amid a split in its ranks and corruption allegations, Abinader and his party took power.

Success in the vaccination process and in keeping inflation to a moderate level helped to consolidate the government, which also drew popularity from the persecution of corruption cases against relatives of former President Danilo Medina and prominent officials in his administration, such as the attorney general and the finance minister. (All have denied the allegations.)

Turning its sights to reelection after the pandemic, the Abinader government added public jobs and expanded social programs like the Supérate conditional cash transfer initiative. And, on foreign policy, Abinader rallied the nation around the idea that instability in Haiti posed a “threat” to the Dominican Republic, seeking to project the sense he was determined to defend Dominican sovereignty from foreign pressure—bringing to the fore an issue that hadn’t been a top concern in elections since the mid-1990s.

This recipe evidently proved an electoral success: preliminary results indicate that the PRM and allies will win 29 senators and Fuerza del Pueblo three (for a total of 32). They had won around 60% of the votes in the February municipal elections, including the largest municipalities.

This second term will be key to define Abinader’s legacy. Will he focus on his own political ambitions, or in helping to institutionalize Dominican politics and improve the standard of living of most Dominicans?

—

Espinal is professor emeritus of sociology at Temple University