The regional and parliamentary elections on May 25 confirmed Venezuela’s longstanding descent into dictatorship, and they most likely set the stage for a contentious relationship with the Trump administration in the years to come. The electoral council announced a landslide victory for President Nicolás Maduro’s ruling socialist party, securing 82.7% of votes for the National Assembly and winning all but one of the nation’s 24 governorships. The opposition, still reeling from a fraudulent presidential election last year and ongoing repression, chose to boycott the vote.

U.S. officials condemned the so-called election, labeling Maduro’s regime “illegitimate” once more. They also pushed back against the election of a governor for the Essequibo, an oil-rich region that neighboring Guyana has controlled since 1899, but that Venezuela has long claimed as part of its territory.

Over the last eight years, the U.S. has tried two basic approaches to restoring democracy in Venezuela. The first Trump administration pursued a punishment and pressure campaign, ratcheting up sanctions against the country and recognizing Juan Guaidó as the legitimate president over Nicolás Maduro. Joe Biden’s administration advocated for a more measured and pragmatic approach of engagement and gradual reform, including offering sanctions relief in exchange for concrete democratic concessions. Most notably, in October 2023, ahead of last year’s presidential election, oil sanctions were briefly lifted under the Barbados Agreement in an effort to produce a free and open vote.

Both approaches have failed to bring about fundamental change. Meanwhile, over the past decade, 7.7 million Venezuelans have left the country amid an economic debacle and rising repression, exerting pressure on countries and governments throughout the Americas. Of these, the U.S. has taken in more than half a million migrants, and Venezuelans constituted the second most common nationality of migrants—after Mexicans—encountered at the U.S. southern border under Biden.

The new Trump administration has come out swinging again. Trump recently revoked a Biden-era license that had allowed U.S. oil firm Chevron to operate in Venezuela, despite the company’s intense lobbying efforts to continue its operations. Chevron is now being forced into a holding pattern that allows it only to maintain its infrastructure in the country, depriving Venezuela of valuable tax-and-royalty payments that come from pumping oil. Operating through four joint ventures with the state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), Chevron accounts for approximately 220,000 barrels of crude oil per day in the country, which is about 25% of the nation’s total production. Now, Maduro will need to supplement these missing revenues with other sources and international partners.

At the same time, Venezuela is also caught up in the dragnet of Trump’s tariff policy. The U.S. has slapped 25% levies on buyers of Venezuelan oil, scaring some countries off purchases and pushing Venezuela deeper into the arms of China, its biggest market for oil.

Additionally, in the U.S., Trump is going after Venezuelans. He invoked the Alien Enemies Act for the first time since WWII to target the Venezuela-based Tren de Aragua gang. That comes as the administration has revoked temporary visas for Venezuelans at a massive scale and apparently seeks large-scale deportation.

The sequence of events raises an urgent question: How will the U.S.-Venezuela relationship unfold in the months and years to come?

Photo by Jimmy Villalta/VWPics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Where to go from here

The space for building a relationship based on mutual interests has shrunk, as the U.S. also encourages Venezuela to pursue democratic reforms and economic stabilization. This space is further limited by the hardline position of Secretary of State Marco Rubio and several Cuban-American lawmakers from Miami, who have consistently opposed any cooperation with Venezuela and whose votes are crucial for any legislative success by Republicans, considering their razor-thin majority in Congress. Venezuela’s regional and parliamentary elections have only reinforced their resolve against the Maduro regime.

Even so, the Trump administration and its allies are not united in their approach to Venezuela. Some U.S. oil executives have urged Trump to make a deal with Maduro that would loosen oil sanctions on Venezuela in exchange for an effort to crack down on migration. They argue that such a policy would ease energy prices in the U.S. as inflation continues, and that profits could also be channeled for public benefits.

More broadly, there is ongoing discussion over whether the U.S. should restart formal diplomatic communication with Venezuela to facilitate dialogue on key issues. Many longtime observers argue that the U.S.-Venezuela relationship should shift away from ideological standoffs toward promoting gradual reforms and regional stability.

But the voices for results-driven diplomacy and pragmatic engagement have been repeatedly undermined by new political developments. Maduro’s regime has openly cracked down on the opposition, and human rights abuses are widespread. Dozens of officials and people connected to Venezuela have been accused of drug trafficking, money laundering, and other transnational crimes. Many are subject to sanctions and criminal charges.

The Russia-China factor

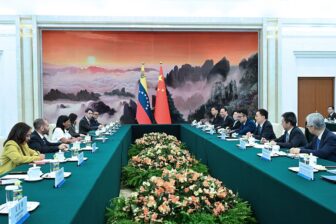

Against the ongoing backdrop of poor relations with the U.S., Venezuela has forged ever deeper ties with Russia and China. Both major powers are buying Venezuelan oil and investing in the country’s economy and infrastructure. That further widens the divide between the U.S. and Venezuela, particularly in terms of the competition between global rivals in a geographical area that the U.S. has long considered its sphere of influence.

The penchant of both Trump and Maduro to personalize their power could lead to surprises. Rather than his typically blistering anti-U.S. rhetoric, Maduro congratulated Trump on his November win and called for a “new start” in bilateral relations between the countries.

But Trump and Maduro each depend on crucial backing from hardliners, and neither leader wants to appear weak. This limits their ability to find common ground, and makes it likely that the U.S.-Venezuela relationship will be a rocky one in the years to come as Trump attempts to compel Venezuela to take back tens of thousands of migrants, while Maduro seeks leverage—such as further ties with Russia and China—to achieving sanctions relief and oil deals. The tense nature of the relationship could very well result in deeper isolation for Venezuela, pushing it closer to the status of Cuba within the hemisphere.