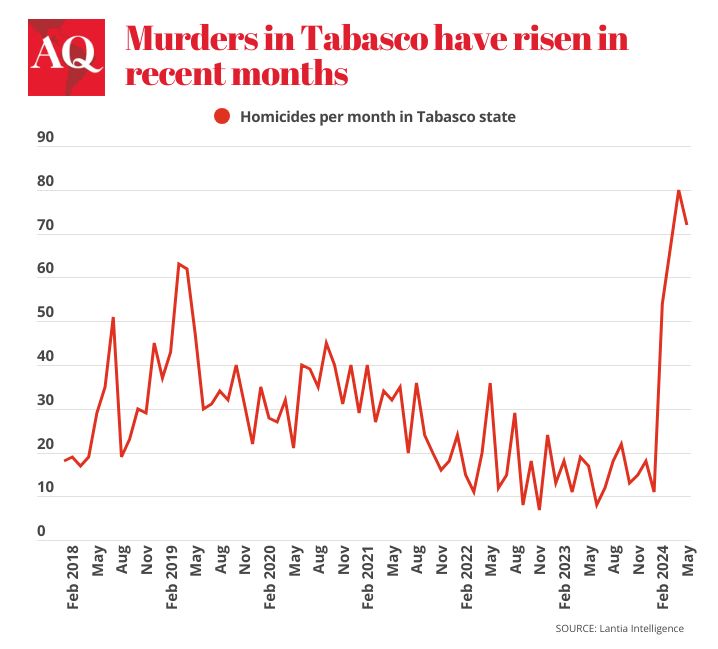

VILLAHERMOSA, Mexico — Tabasco, once called Mexico’s “Eden” by a past state governor, is known for its oil, torrential floods, and for being the home state of outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador—not cartel violence. But with monthly organized crime-linked homicides up 400% since last year as of May, that’s changing.

Last December, violence reached new extremes, mirroring a security crisis already raging in the neighboring state of Chiapas and which threatens to engulf other southern states. Politicians from Morena, the party of AMLO and President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum, governed most of those states before the June 2 elections. Now, they govern all of them.

The South’s drug-related violence has been years in the making, and analysts warn that despite recent economic outperformance, one of Mexico’s poorest and most neglected regions—from which citizens still migrate in large numbers—could slide even further into instability.

Behind the recent turmoil in Tabasco is the aggressive takeover of the state by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). Tabasqueños have seen buses torched, businesses fold under pressure from extortion, and as many as 80 organized crime-linked homicides in a single month, according to Lantia Intelligence, a consulting firm monitoring violence and criminality in the country. Days ago, three human heads and a narco-manta—a warning from CJNG to its remaining rivals—were left outside a kindergarten in Macuspana, the municipality that includes AMLO’s hometown. In the state of Chiapas, the violence and accompanying mass displacement are even worse.

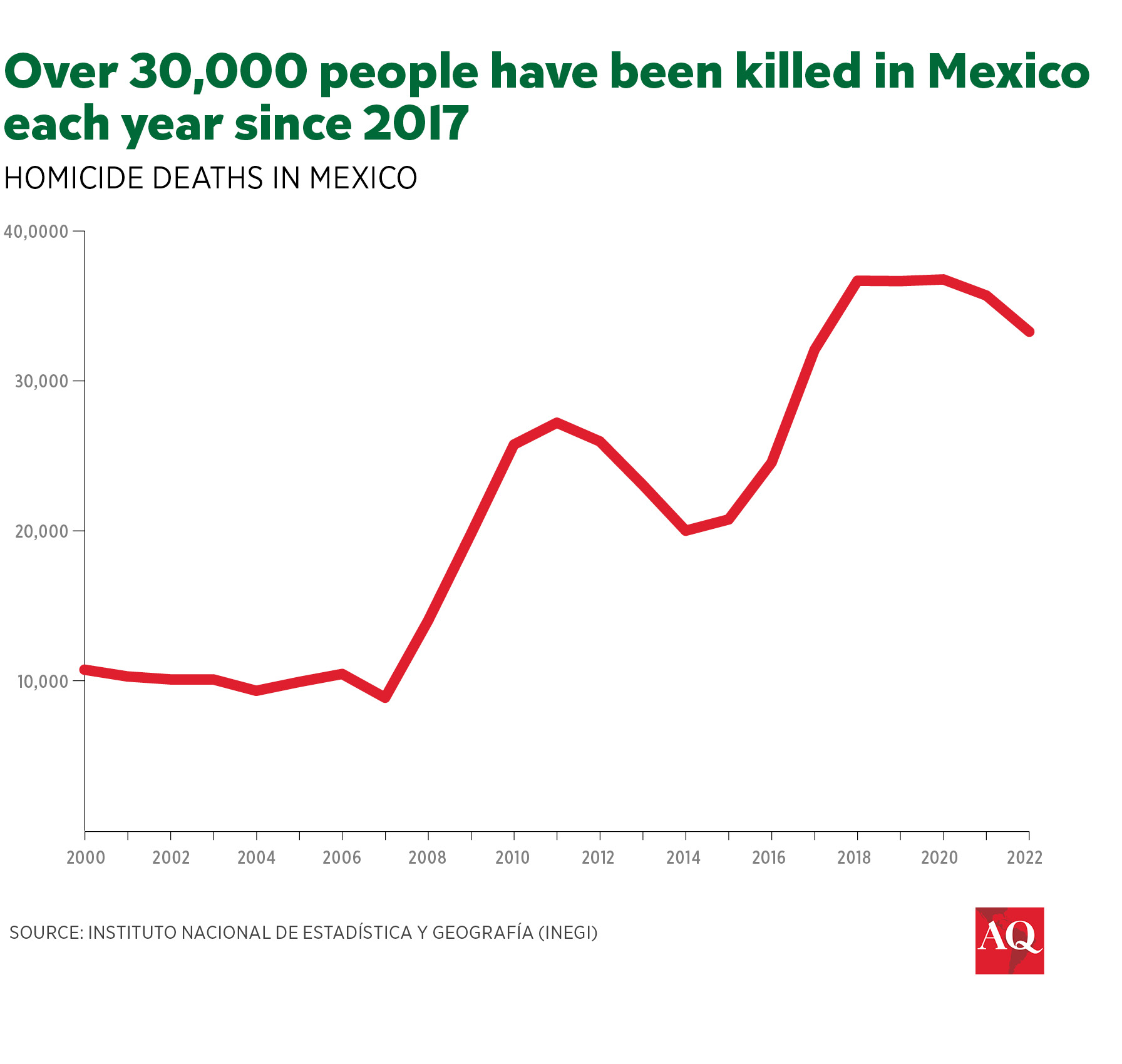

For the past six years, AMLO and his party’s governors have wavered between denying cartels’ presence in the state and developing a response. Mexico, with the world’s third-highest level of organized crime activity after Myanmar and Colombia, according to the Global Organized Crime Index, has expanded the role of the military in combating its thriving cartels, allowing it to oversee domestic law enforcement until 2028. Last year, the federal government earmarked $17.8 billion for national security and defense—an increase of 7.5% vs the 2022 budget—and frequently deployed a military-run National Guard to contain organized crime-fueled violence. But as Tabasco and Chiapas show, increased spending and militarized police won’t resolve the crisis on their own. Nationwide, over 30,000 people have been killed each year since 2018, the year AMLO assumed the presidency.

“Fifteen years ago, we read about things like this happening in Michoacan. But now, not a day goes by here without an assassination.” So said a social leader I interviewed in a bare-bones brick office in Villahermosa, the state capital. Like the other sources quoted in this article, he requested to remain anonymous, citing fears over rising criminal activity.

Violent turnover

Whether they’re outsiders or locals who have changed affiliation—tabasqueños I spoke with held varying opinions—CJNG’s foot soldiers in Tabasco are applying radical methods. Rather than subordinating local gangs, CJNG has been systematically eliminating them to monopolize local drug distribution, especially for the growing meth market. There’s been a boom in extortion, which has spread from a few traditional hotspots to cover large swaths of the state and economy in just a few years, according to press reports and local reporters I interviewed.

Violence has flared amid the deterioration in state security forces under the outgoing state government. Adán Augusto López—a longtime AMLO ally and former Morena presidential hopeful—won the governorship in 2018 and appointed a state security secretary with ties to CJNG, according to military intelligence documents made public in the 2022 Guacamaya leaks. Asked about these ties, López initially denied them. Recently, however, he said he had “maybe” been told about them.

Augusto López’s security secretary forged a criminal group within the state police, nicknamed “the dump truck,” but the group later fragmented, and CJNG set its sights on eliminating one of its factions. On December 22, 2023, hitmen rained ammunition on the security secretary’s house, forcing his resignation. “I had never heard so much gunfire in my life,” one of his neighbors told me. Mexico’s national guard, locals told me, showed up late.

Not everyone is sticking around to see how things develop. In 2021, the director of one of the state’s largest prisons resigned and fled the country after receiving death threats. Several chains, including Oxxo and Farmacias Guadalajara, have cut back operations in hard-hit neighborhoods and municipalities, taking jobs with them. Villahermosa residents are opting for the safety of Mérida, in Yucatan state. Most tabasqueños, over half of whom live in poverty, have no such options.

Many locals I spoke with told me they expected violence to subside following the elections as CJNG consolidates a criminal monopoly. But some, including a priest I interviewed, were more pessimistic: “We’re not as bad off as Chiapas, but soon we might be.”

Change within Morena

President-elect Sheinbaum won Tabasco by 70 points, a larger margin than any other state—and Morena’s gubernatorial candidate, Javier May, AMLO’s former tourism and welfare secretary, also won handily, becoming the first candidate outside Tabasco’s tight-knit local elite to win the governorship.

Why the landslide amid so much violence? The impact of cash transfers, given Tabasco’s high poverty rate and the state’s recent economic growth (almost double the national rate in 2023, fueled by major infrastructure projects), contributed.

But that doesn’t mean Tabasco’s Morena voters aren’t concerned with security—or that they’re ready to give their new leadership a free pass. Local Morena voters I met were uniformly fed up with the outgoing state government and wanted change within the governing party, not outside it. Many looked favorably on May, who reduced violence in his hometown of Comalcalco as mayor from 2016-17 and gained a reputation as a shrewd dealmaker.

One such voter was a science teacher at a public middle school in Villahermosa for whom security is nothing abstract. She only narrowly survived being shot during an armed robbery, yet she voted for Sheinbaum. “I’m not happy with the Morena government we had in Tabasco,” she told me. “But I still believe in the Cuarta Transformación and its national project, even if the results aren’t apparent right away.”

Stabilizing the south will likely require transporting and adapting tactics that have had some success reducing rates of high-impact crimes in wealthier parts of the country, like Coahuila and Mexico City. Those include having state police and prosecutors coordinate, increasing police salaries, training and screening, and taking an approach to crime-fighting that puts violence reduction first.

But even with such improvements, the sheer profitability of migration and drug routes in southern Mexico may keep criminal groups fighting. Until now, Morena has also been willing to turn a blind eye to candidates who associate with organized crime as long as they jump on the bandwagon. That makes the problem even more intractable. Sheinbaum needs to adopt a less permissive approach to members of her party who allow crime to flourish.

If restoring security under these conditions sounds almost impossible, that hasn’t yet worn out tabasqueños’ resilience. “We have to hope things get better,” explained the leader of a union of small and medium-sized enterprises. “We have to.”