This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the education crisis

When asked if she believes in the Virgin Mary, Clara, the protagonist in Nathalie Álvarez Mesén’s debut feature, Clara Sola, responds flatly: “I can do whatever I feel like.” Though she seems self-assured, her words reflect aspiration more than reality. After all, Clara is a 40-year-old woman tightly controlled by those around her, with little to no say over her own movements, health, or even clothes. Hers is a constricted life, and Álvarez Mesén’s intimate film reveals what becomes of it when these decades-old community bonds come undone.

In the rural Costa Rican village where Clara lives, everybody knows she’s a healer. Because she can perform miracles, her family and neighbors believe she can communicate with the Virgin Mary. At her mother’s behest, Clara entertains visitors—sick people eager to heal—and presides over communal prayers at home. The work of a saint is a full-time job. When she gets time off, we almost always see her alone, wandering in the rain forest. Nature is where Clara feels most at ease. So it comes as no surprise that after years of quiet endurance, her small acts of rebellion materialize with the help of animals, trees, water and dirt.

Shortly before a mass, for example, Clara decides to lie on the muddy ground. When she goes on to greet fellow churchgoers in her sullied white dress, her mother is incensed. “The Virgin told me to do it,” she offers as an excuse. A few days later, learning that her white mare, Yuca, might be sold, she releases her by a river. The family spends hours trying to find the horse, but their search is in vain. Yuca stays free. Clara’s revolts lead her closer to nature, and perhaps most importantly, they enable release. This liberating process is best exemplified by the most persistent and powerful urge that Clara works to actualize: the full expression of her sexuality.

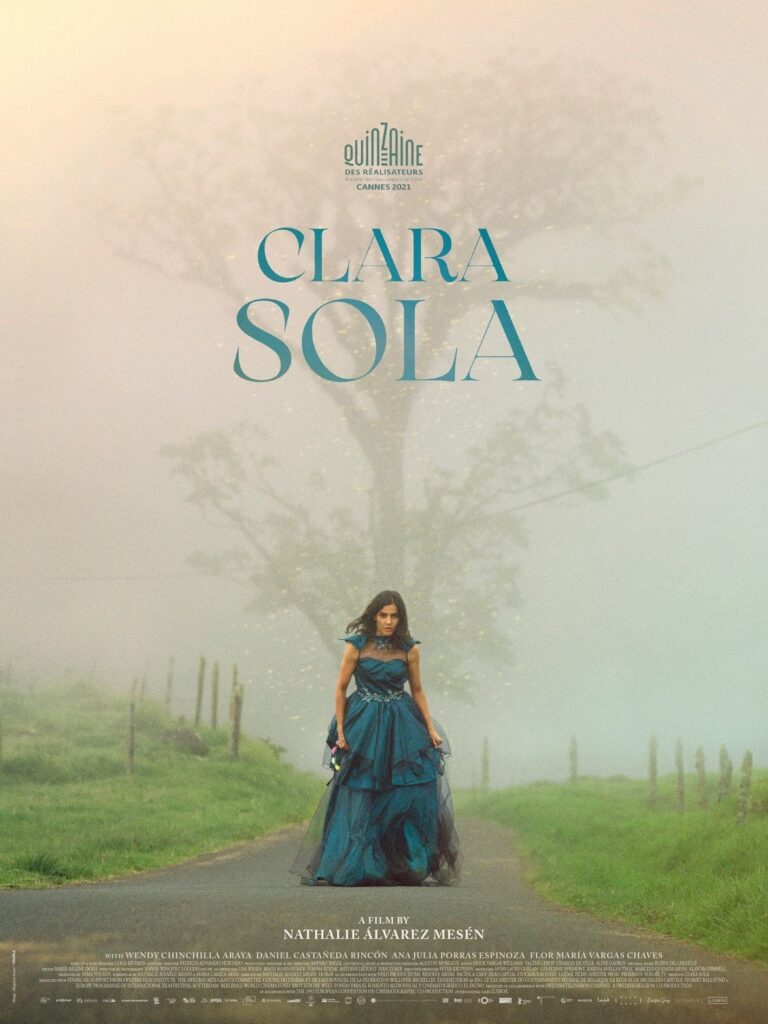

Clara Sola

Directed by Nathalie Álvarez Mesén

Screenplay by Nathalie Álvarez Mesén and Maria Camila Arias

Starring Wendy Chinchilla Araya

Costa Rica

AQ Rating: (4/5)

The clash between sexual desire and freedom is at the heart of Clara Sola, and in this sense, Álvarez Mesén’s film addresses an age-old Christian conflict. Clara is often turned on, especially by the telenovelas she watches with her family, yet whenever she begins to masturbate, she is chastised and forced to rub her fingers in red chili peppers. In line with the prevailing view in Clara’s village, her mother calls her “vile” and “disgusting” whenever she gives way to these unauthorized sexual feelings. More than anybody else, Clara must aspire to emulate the Virgin, that “New Eve” who remedied primeval woman’s original sin.

The traditional Catholic notion of sex as tainted derives from Saint Augustine’s reading of the Book of Genesis. For Augustine, concupiscence, or libido, split from the human will when Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit. Until that moment, as the literary historian Stephen Greenblatt has argued in The New Yorker, Augustine believed humans were perfectly free, for the only period in their entire history. Afterward, in Greenblatt’s reading, “because they had spontaneously, inexplicably, and proudly chosen to live not for God but for themselves, they had lost their freedom.”

Clara turns this cause and effect inside out. For her, lust strengthens freedom, not the other way around. Through an exploration of her sexuality, she gains the ability to assert her individuality, and this newfound autonomy inaugurates a return to nature that is not inscribed in Christian terms. Clara Sola’s invocation could not be clearer: Reentry to paradise does not require a purification of our desires. It demands an embrace of them.