This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s election super-cycle

Fernando Botero’s art is instantly recognizable on account of its fulsome figures. The late Colombian painter and sculptor (1932-2023) is famous for hundreds of portraits, still lifes and sculptures that evoke everyday scenes—but many of his best, and least-appreciated, works are overtly political.

The son of a seamstress and a muleteer, Botero came of age during Colombia’s undeclared civil war, known as La Violencia (1948-58). He sold his first piece of art at 16, and worked as a newspaper illustrator while still in high school. During the first half of his prolific career, Botero gained a reputation for humorous refashionings of Renaissance masterpieces such as Pope Leo X (1964), The Arnolfini Portrait (1978) and the Mona Lisa (1978). He also used his signature style to satirize the pomposity of Latin American clergymen, generals and dictators.

Although politics was not then a major theme in his art, Botero made powerful works that record and lament the Colombian conflict. For example, his mural The Massacre of the Innocents (1960) takes a biblical theme explored by the Renaissance master Peter Paul Rubens and brings it to the Colombian context. And in Guerra (1973), he paints scores of corpses, including his usual cast of clergymen, soldiers, politicians and prostitutes, as though they have been dumped in a silo.

Botero’s work became more consistently political as violence in Colombia evolved from a predominantly rural and bipartisan conflict into a combination of guerrilla insurgency, drug trafficking and terrorism that afflicted cities such as his native Medellín.

Botero was personally affected. In 1994, he survived a near-kidnapping in Bogotá. A year later, terrorists from an umbrella organization representing several armed groups killed 23 people when they blew up his sculpture of a dove in Medellín’s Parque San Antonio. In response to the bombing, Botero inscribed the disfigured original with the names of the victims, and created a replica dove to be displayed beside it.

Botero’s exploration of the Colombian conflict became much more frequent. In 2000, when he opened his exhibition Testimonies of Barbarism, he explained: “I was against that art that becomes a witness to its time, like a combat weapon. But in view of the magnitude of the drama in Colombia, the moment came when I felt the moral obligation to leave a testimony of such an irrational moment in our history.”

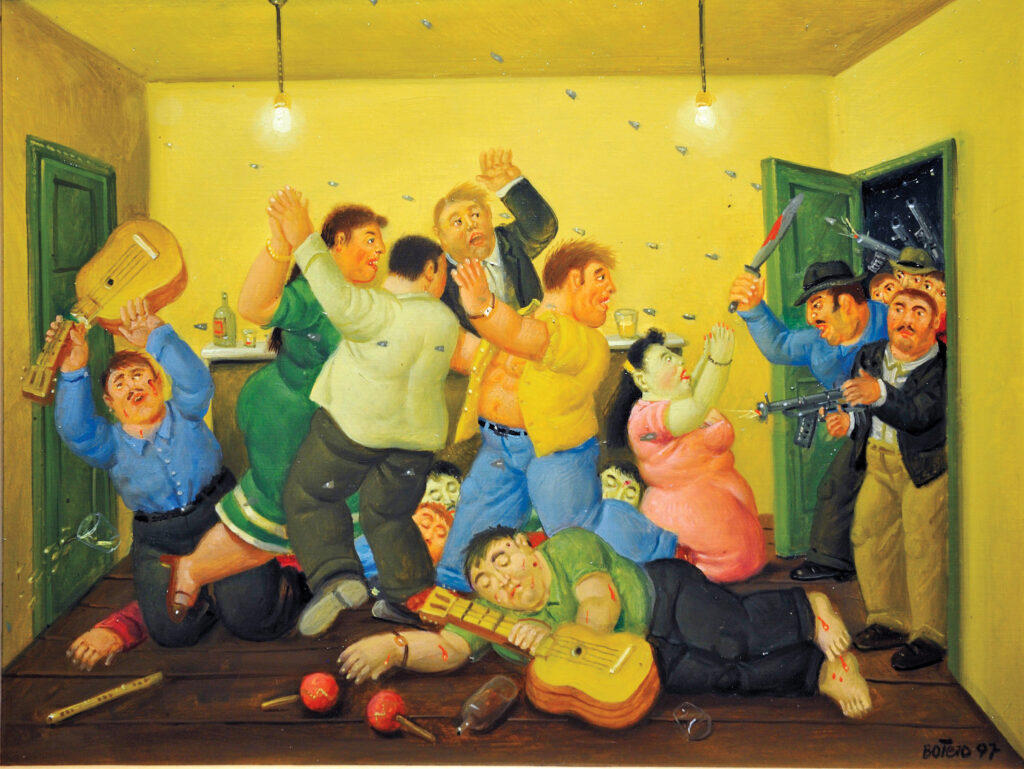

In this period Botero painted works such as The Massacre on the Best Corner (1997) and The Car Bomb (1999). The characteristically soft contours of Botero’s characters provide a sharp contrast between form and theme that, rather than trivializing terrorism, makes the paintings even more jarring.

A stylistic exception is Mother and Child (2000), a harrowing portrait of two skeletons in which Botero abandons his typically generous depiction of form. The painting, with its tender pose, is especially eerie given the scene’s association with the Madonna and Child—the two Christian figures most associated with life. Resting on the mother’s shoulder is a condor, a scavenger bird and a symbol of Colombia.

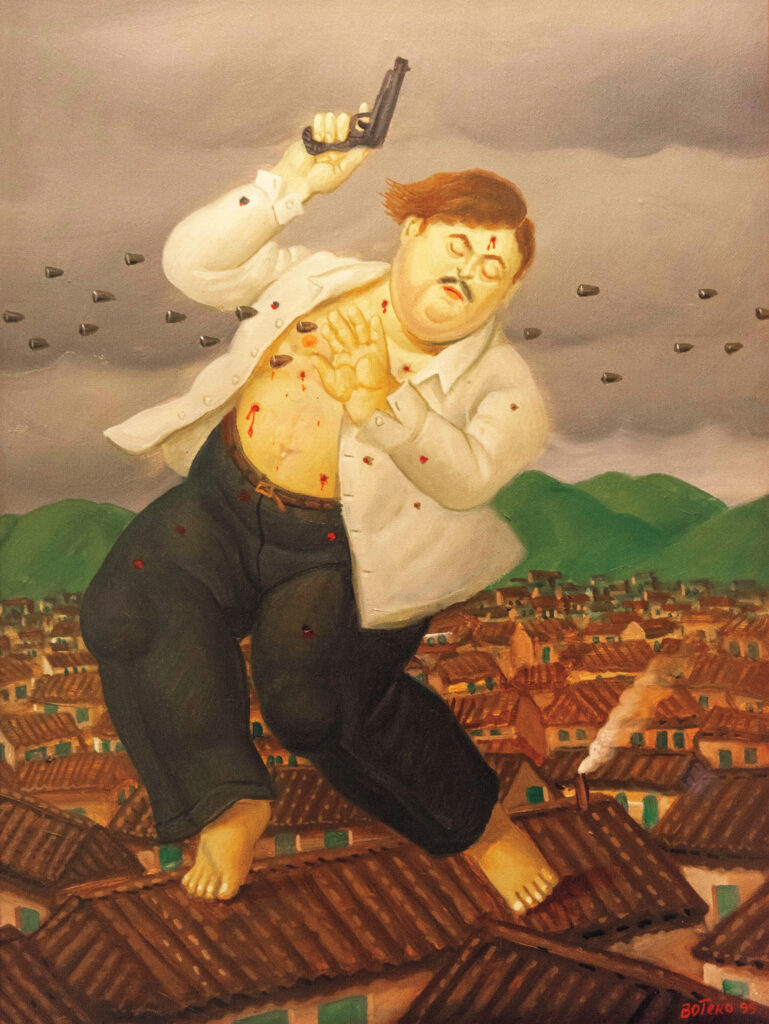

Not all of Botero’s political art was so unequivocal. In Pablo Escobar Dead (2006), the leader of the Medellín Cartel lies peacefully on a ceramic-tiled roof, in front of the colonial city and green mountains, and beneath a dark sky. He is still holding a revolver. Botero paints Escobar as though he is merely sleeping. Medellín’s violence is not resolved by the bullets in Escobar’s stomach and face. The painting makes one expect that as the sun rises, so will Escobar.

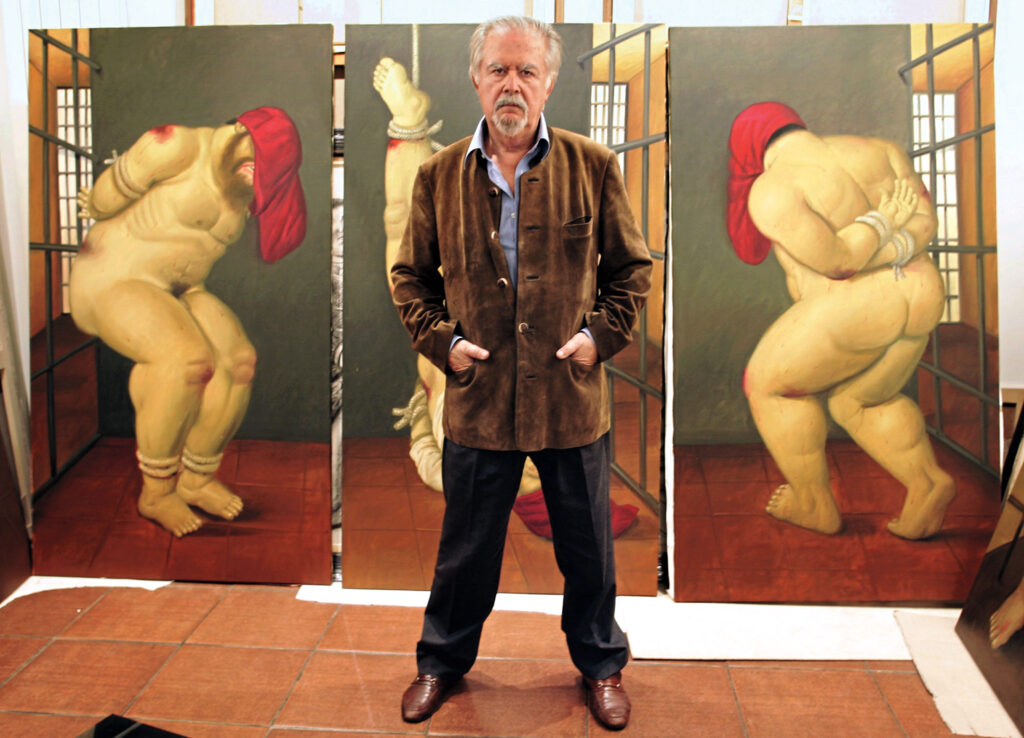

In 2003, scenes from the Abu Ghraib prison outside Baghdad led Botero to work on the most politically-charged subject of his career— the torture of Iraqi prisoners by the U.S. Army. In 2005, he unveiled nearly 200 drawings and paintings of human rights violations. The Abu Ghraib series was an artistic departure for Botero. Whereas his characters usually have inscrutable faces, Botero gives the prisoners expressions of pain, anguish and humanity. What is more, he hides the torturers from view, granting the prisoners the dignity of being the paintings’ subjects. Even more than in The Massacre on the Best Corner or The Car Bomb, Botero’s rounded forms stoke the viewer’s pathos because their tender composition contrasts so starkly with the scene’s brutality.

Botero believed the principal importance of his most political paintings was in bearing witness to events. “I am not making [politically] committed art—art that aspires to change things,” he said in 2006. “I do not believe in that because I know very well that art does not change anything.” Nonetheless, the Abu Ghraib series and the paintings of Colombia’s violence are modern equivalents of Picasso’s Guernica.

Botero may have been reluctant to paint these scenes, yet he produced some of modern art’s most politically demanding works. Throughout his immense oeuvre, he was not only a humorist and a satirist, but a chronicler of ferocious violence.

—

Rey is a British-Colombian writer based in New York with writing in the Spectator, the Financial Times and the New Statesman

Tags: Colombian civil war, Cultura, Fernando Botero, Visual art

)