“We want opportunity, not handouts,” a young leader from a working-class neighborhood in Medellín told me last Saturday. The message was clear: If the government tries to solve the social unrest sweeping Colombia by handing out more cash, nothing will improve. The path lies in helping the youth to progress, to channel their talent and follow the path of Colombian cultural icons like J Balvin or Karol G. Our youth don’t belong inside, in their homes, where they have been forced to stay for too long. They belong to the outside world.

Their seclusion from society began long before the pandemic.

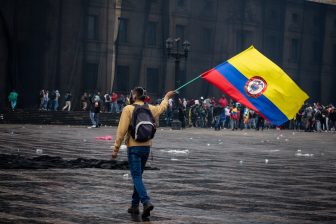

COVID-19 has, of course, made things much worse. Urban poverty grew 10 percentage points in 2020, to 42%. In Bogotá and Cali, it rose by 13 and 14 percentage points, respectively. Nearly 2.1 million people fell into poverty last year in Bogotá, Medellín, Cali and Barranquilla, Colombia’s largest cities. The share of Colombians aged 14-25 that neither study nor work soared to 27.1% in 2020 from 21.9% the year before. Disenfranchised, pent-up and feeling hopeless about their future, these urban youths are at the heart of the protests now entering a third week with no end in sight.

This is not the typical crisis that the world is accustomed to seeing in Colombia. It does not come from the isolated rural areas where guerrillas, organized crime and drug traffickers coexist; in fact, poverty in the countryside actually fell a bit last year. This is not another episode in the long history of narcoterrorism; members of groups like the ELN and so-called dissident FARC may be present in the demonstrations, but they are not the main driver. It is always tempting to blame them for everything that is wrong in Colombia, but that does not mean it is right.

No, this time it is the young and urban Colombia that is rejecting the status quo. There is a disconnect between their daily problems and Colombian politics, where divisiveness and acrimony consumes most of the time in the news but do not help the young improve their lives. They have aspirations and the country is failing them. Politicians do not help. They are part of the problem. The young cite corruption as their main concern in polls, well above the dire and worsening economic conditions they face.

This is a leaderless movement. It is not associated with a specific name or a visible face. It makes it stronger, but also much harder to understand and respond to. It requires bold actions, a clear message, and the making of new leaderships.

A tax reform was the proximate trigger. Asking the middle class — those that earn between $600 and $1,000 per month — to start paying income taxes and VAT on basic goods, was a mistake. Withdrawing the reform did not solve anything reflecting that the problem is deeper. The first order of business is to speed up the way out of the pandemic and end the series of lockdowns and curfews that are becoming increasingly ineffective. The country desperately needs more vaccines, and Washington has so far not been receptive to requests to give Colombia a hand. President Biden should pay attention to what is happening.

On the tax side, few question that Colombia needs additional revenues to pay some of the pandemic bills and begin — in 2022 — to stabilize its public finances. Rating agencies have said that unless there are clear steps in this direction the country seriously risks a downgrade that would cost its investment grade status and put Colombian bonds in junk territory.

The business associations understand this well and made a counterproposal to the government well before the riots began. They could shoulder more of the cost in a more moderate reform that would still pay for additional expenditures to reduce social tensions. But the government initially insisted on its plan, avoiding an increase in corporate taxes. Centro Democrático — the president’s party — took distance from the bill, and other parties followed, causing a political crisis before this became a mass protest. Now it is much more than that.

The fact all this is happening a year before congressional and presidential elections is not a coincidence. Gustavo Petro, an opposition candidate from the left, is easily leading the polls, suggesting that there is discontent and that people want alternatives. If the outcome of this wave of protest is more repression rather than constructive dialogue, it could be the tipping point that puts Colombia in the direction of populism and demagoguery from the left. If the negotiations lead to bold decisions that improve social and political cohesion, moderation and pragmatism could still have an opportunity in next year’s elections.

What seems to be ruled out is the continuity of the politics of hatred and polarization that have characterized Colombia in the past several years. Colombia is an unequal, regionally divided and very diverse country. Governing from one side of the political spectrum is a recipe for disaster. President Iván Duque still has time to bring in individuals that represent sectors that have been excluded and marginalized. It would make his life, and that of Colombia, a lot easier. But it would also move the political spectrum to the center, something that his own political party will resist.

The Comité del Paro, the strike committee with which the government is negotiating, has presented an 18-point list of demands. The first item on the agenda: Unconditional and comprehensive implementation of the 2016 Peace Agreement. That says a lot. Colombia needs to de-politicize the peace agreement and make it part of the solution to the problems today, not the problems of the past.

One way to move forward is to stop thinking about the peace agreement in terms of concessions made to the much-disliked former FARC combatants. The peace agreement is about building a new social contract, where marginalized groups will have more political representation while bringing the state in, in the form of roads and schools, to some parts of Colombia for the first time in our history. Finding alternatives to the traditional war on drugs is also necessary. All these steps are needed, with or without a peace agreement. But if they help end a conflict, they are even more welcomed.

The list of items for negotiation also includes four points related to the environment, ranging from stopping deforestation, establishing better controls on the use of natural resources, protecting endangered species, and reducing carbon emissions in public transportation. It is impossible to say that these issues cross a red line. They seem very much in sync with where the young stand, in Colombia and elsewhere.

But the most important task is clearly to address the urban youth crisis at the heart of this unrest. There are no easy fixes. Reframing the policy debate – which has been too focused on the peace agreement– is essential. The new items should be the ones that are relevant for the young in today’s world. Providing free tuition for public universities and technical training, as President Duque announced this week, is a positive first step. But securing jobs is equally important. Transforming the job-protection program created during the pandemic, and converting it into a job-creation initiative, is necessary. Hiring workers in Colombia is extremely costly, due to social security and other payroll contributions. A waiver is needed, including a subsidy to salaries paid to young workers. Creating a special credit facility — with seed capital — for young entrepreneurs is also crucial. Climate policies are a great tool to create trust between the young and the government.

In my view, we are witnessing the dawn of an era in which the youth will be the agents of change. They are telling the traditional politicians that they are ready to replace them in order to make the country more democratic, less corrupt, less unequal. Who will lead this change remains to be seen. One thing we know: It will not be the old guard. And I would add, let’s hope it will not be the opportunists that will try to seize the moment, only to plant the seeds of greater frustration ahead.

—

Cárdenas is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University and was Colombia’s finance minister from 2012 to 2018. Follow him on Twitter @MauricioCard.