MEXICO CITY – Most experts agree that President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s proposed reform of Mexico’s energy sector will delay its transition to cleaner fuels. Claudia Sheinbaum, Mexico City’s environmental scientist-turned-mayor, is not among them.

For now, congressional opposition and horse-trading have stalled López Obrador’s attempt to return state producer CFE to the center of Mexico’s energy industry. But in the administration’s ongoing sales pitch, Sheinbaum remains a central — and credible — figure.

The 59-year-old was part of an IPCC climate change panel that won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2007, and has bolstered her green credentials since becoming mayor in 2018 — including through a massive expansion of rainwater collection programs, significant investment in modernizing waste management, and reforestation projects.

She couches her support for the reform, in press conferences, interviews and on social media, in terms of “energy sovereignty.” Though some private electricity generation has been permitted in Mexico since the late 1990s, López Obrador presents his plan foremost as a corrective to constitutional changes implemented by his predecessor in 2013. Those changes, he says, sidelined CFE and left consumers at the mercy of rent-seeking private producers.

Most analysts, however, say that by giving dispatch priority to CFE-generated electricity (rather than to renewable production, as the 2013 reform mandated), the proposal would make Mexican electricity not only more expensive, but also worse for the environment. CFE is a significant hydropower producer, but only 11% of its clean energy generation comes from wind and solar.

This isn’t the first time Sheinbaum’s ardent support for López Obrador’s so-called fourth transformation of Mexico has come into apparent conflict with her reputation as an innovative problem solver. Her approach to COVID-19, for example, differed from the president’s in small but significant ways.

“On one side (Sheinbaum) is loyal to an illogical ideology, and on the other she has a highly logical technical outlook,” said Ana Lilia Moreno, a program coordinator at México Evalúa who has analyzed López Obrador’s reform proposal. “Those two things clash.”

How to square the circle?

Mexico’s next presidential election isn’t until 2024 but, in the words of one prominent local journalist, “(Sheinbaum) would say she’s not campaigning to be a candidate, but her supporters would.”

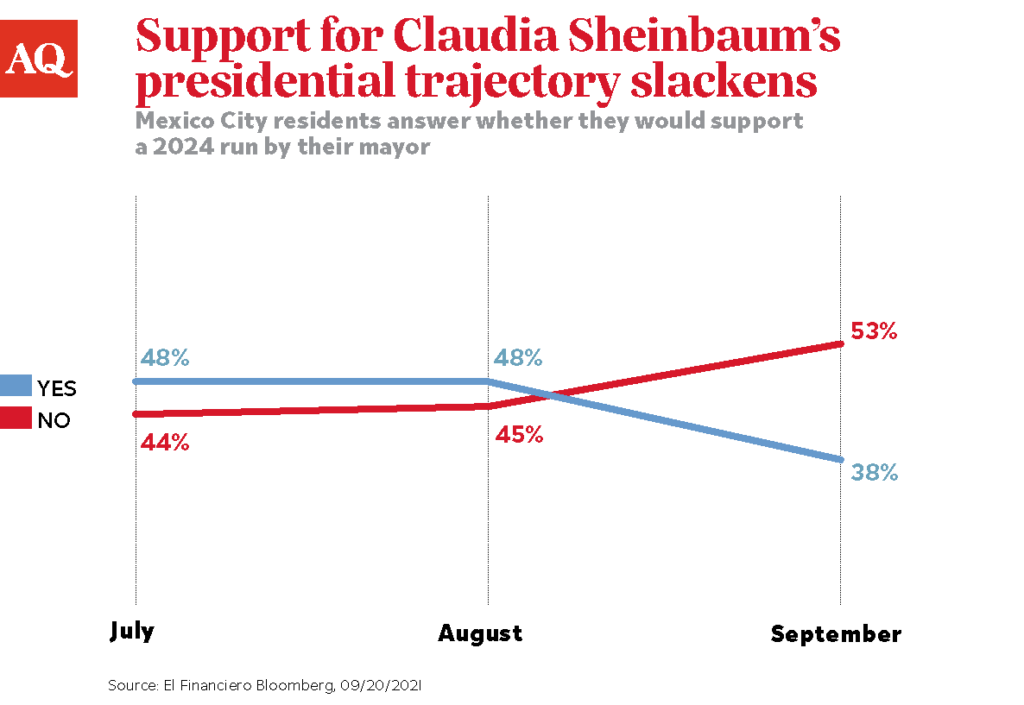

Among those supporters may be López Obrador himself. Polls show Sheinbaum leading or tied with Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard in the race to represent MORENA, López Obrador’s party, in the next election. Whoever wins the nomination, officially through an internal survey in 2023, would likely begin the national race as the favorite.

Hints of López Obrador’s preference for Sheinbaum have been hard to ignore. A photo of the president holding her arm aloft after a public event in September reminded many of the so-called dedazo, an implicit coronation of presidential successors that was standard practice during decades of one-party PRI rule.

Sheinbaum has also appeared to align herself more closely with the president after local elections in June in which MORENA was trounced in Mexico City. Some party heavyweights reportedly blamed Sheinbaum’s lack of political acumen for the loss. In July, the mayor replaced her government secretary with Martí Batres, a political operator close to the president. Her administration also shed its bright green branding in favor of the maroon and gold associated with the national government, a telling stylistic change that extended to debit cards used to distribute social program subsidies.

It would not be surprising if López Obrador indeed wants Sheinbaum to carry the mantle. She has been in and around his orbit for the last 30 years, starting as a student activist supporting what would become the PRD, the political party that launched López Obrador to national recognition.

Sheinbaum has been especially prominent in advocating López Obrador’s view on the intersection between energy and development, a central pillar of the president’s ideology. They often hit the same notes in the perennial debate in Mexico over natural resources, tapping into a deep well of nationalistic pride and mythmaking that dates back to Lázaro Cárdenas’ expropriation of foreign oil concerns in 1938.

When López Obrador disputed the result of presidential elections in 2006, he made Sheinbaum a secretary in his “legitimate government” that occupied the center of Mexico City for two months; her responsibility was to “defend the national patrimony” from privatization. In 2008, when then-President Felipe Calderón attempted his own reform of Mexico’s oil sector, Sheinbaum was put in charge of the Adelitas, groups of women enlisted into civil resistance by López Obrador who marched, occupied public spaces, and harangued administration politicians “to rescue (Mexican) oil, however they can, with what they can, and wherever they can.”

When not in government, Sheinbaum’s academic pursuits have married energy sustainability with the stated core of both her and López Obrador’s political agenda: reducing inequality or, in administration parlance, “for the good of everyone, first the poor.” Sheinbaum’s doctoral thesis on residential energy use, part of which she researched under the renowned UC Berkeley efficiency expert Lee Schipper, begins “Sustainability? Ask the indigenous people of Chiapas,” an apparent reproach of the top-down imposition of energy policies on marginalized communities.

“(Sheinbaum) without any doubt has a clear ideological compass, she’s of the left and a lopezobradorista,” said Genaro Lozano, a political analyst and professor at Universidad Iberoamericana. But, he says, “She’s more pragmatic than she seems.”

It is in this context that Sheinbaum’s view of the 2013 reform, and the continued efforts to unravel it, can be understood. In a speech in March, commemorating the Cárdenas expropriation, Sheinbaum said she was “convinced” that López Obrador’s energy policy would strengthen Mexican sovereignty and “reduce environmental impact including, yes, mitigating climate change.”

In support of her position, Sheinbaum noted that the president had banned fracking despite Mexico’s continued dependence on natural gas. She also claimed that climate gains from wind projects in Oaxaca — one of Mexico’s poorest states and home to some of the most significant wind energy potential in the world — had come “at a cost to local communities.”

Despite her ideological alignment with López Obrador’s political project, some observers believe a Sheinbaum presidency would look more like her technocratic, data-driven city administration than the president’s “we have our own numbers” leadership. While she often echoes López Obrador’s attacks on the “neoliberalism” of Mexican institutions (including criticism of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, her alma mater), Sheinbaum has also worked with the private sector on local development projects. The city has even benefited from the 2013 reform while she’s been in office, with the metro and other public services buying lower-cost energy through CFE-contracted private generators.

And while her priority has been on public spaces in often-overlooked parts of the city such as Iztapalapa (where painted rooftops under a new cable bus system read “Thank you, Claudia”), that has not stopped her from directing funds to redeveloping the city center, and improving roads and bike lanes in tourist-heavy, up-market neighborhoods.

“Sheinbaum is close to the president … to the point where perhaps she has been pushing more his agenda than her own,” said Eugene Zapata, the Latin America director at the Resilient Cities Network, which analyzes urban environment and development projects. “As we get closer (to the election) it would be great to hear more about her own vision of the country.”