For much of the last eight months, President Gabriel Boric was waiting for a new constitution to be approved before introducing major reforms. It appears the government was counting on the new constitution, produced over the course of a year by a constitutional convention, to provide major definitions on things like health care, education and pensions.

But a funny thing happened to the constitution: Chileans didn’t like it. After the constitution’s defeat in last September’s referendum, Boric was left with no choice but to make his own proposals to address the changes Chileans have appeared to demand. So, in a November 2 national address, Boric presented his plans for an overhaul of Chile’s pension system. But does Boric have enough political capital to get the reform through Congress?

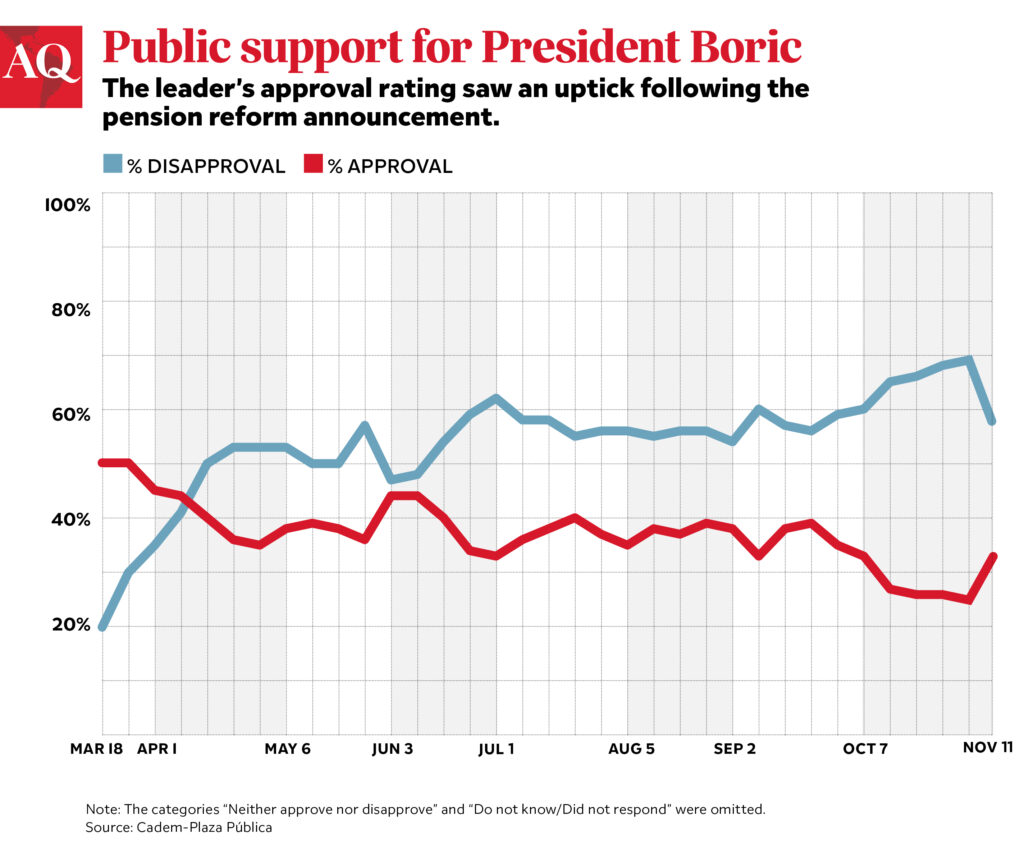

Boric’s popularity does not seem to be a harbinger of legislative success. The latest Cadem poll indicated an eight-point improvement in his approval rating on the back of the pension proposal, but this got him to only 33%.

The reform

Chile’s individual payer system was created in 1980 with two purposes in mind: to create a domestic capital market and, eventually, to provide pensions. The AFP system (the Spanish acronym for Pension Fund Administrator) has been both admired (and copied) and vilified. It was a tremendous success in its first goal but a seeming disaster in the second, so these two perspectives are not contradictory.

There is no question that the pension system needs improvement, which was a major reason that millions of Chileans took to the streets in October 2019. The average retirement pension is about $4,800 per year for men and $3,100 for women. In a country where groceries can cost more than in Europe, this is clearly insufficient.

Boric has proposed a rather moderate, mixed system that would include both a pay-as-you go element as well as an individual payer option. He announced with great pride that the widely hated AFPs would cease to exist, yet he is giving them the option of becoming “Private Pension Investors”—essentially, investment funds.

He also proposed a gradual increase of the universal basic pension (which is universal for everyone except the wealthiest 10% of Chileans) to about $270 a month, as well as a gradual increase of worker contributions, from 10 to 16%. We can expect a vociferous debate on where that extra 6% will go—but one could expect that half would end up in contributors’ individual accounts and half would go to the general pot to help pay for the strengthened public pay-as-you-go system. The public system’s funds would be administered by a seven-member independent board called the “Public and Private Autonomous Investor.” Existing private pensions savings would remain private, and inheritable.

The reform’s success will depend, of course, on whether it makes it through a Congress in which the government lacks a majority. For this, the government needs two things: political capital and an ability to negotiate with members of Congress. Both depend on the popularity of the president and the proposal itself.

Meanwhile, recent events in Congress—from successive pension withdrawal laws that were passed during the pandemic, to the apparent disintegration of the historic Christian Democratic Party, to the more recent election of a new president of the House of Deputies—show that party discipline is practically non-existent. The Communist Party, a member of the governing coalition, cannot be too happy with the pension proposal maintaining such a strong private element, although, disciplined as always, they’re toeing the party line for now. The No More AFP movement, however, has been openly critical.

In order to sell the proposal, the government will have to distill a complex piece of legislation into two or three talking points. It helps that the bill is moderate, containing something for everyone. At least on paper, it does the two things that most Chileans have been asking for: It increases pensions and gets rid of the AFPs. It also leaves savings intact, maintaining the private system under a different name, while adding a pay-as-you go portion.

On its merits then, Boric might be able to convince Congress and even the private sector, which is eager to maintain access to the capital that the AFP system built as well as the AFPs themselves. Private sector players will undoubtedly lobby to maintain as much as possible, but they realize—looking back over the last three years—that they’ve dodged a bullet with this proposal. They might even pressure parties on the right, which may not be inclined to cooperate on the reform, to support it.

Boric came to power promising the end of the very unpopular AFPs. If he manages to get this one reform passed, no matter how moderate, he will be able to claim a major victory. Still, recent polling shows that the public is more concerned with rising crime, employment and inflation.

So while Boric and those around him hoped to offer a transformative government, reality has crept in, bringing questions of everyday governance—crime and the economy—to the fore. Boric may believe that his legacy is tied to the capacity to deliver on the changes that protesters were calling for in 2019, but in reality, his political future depends on the ability to provide solutions to these very basic functions of government. Boric will need to get this balance right to pass the reform—and prevent his own early retirement.

—

Funk is assistant professor of political science at the University of Chile’s Faculty of Government and a partner in Andes Risk Group, a consulting firm.