Even back in 2019, when widespread protests sparked a movement to rewrite Chile’s constitution, it was hard to deny that the country was tired of traditional politicians – and wanted some fresh faces.

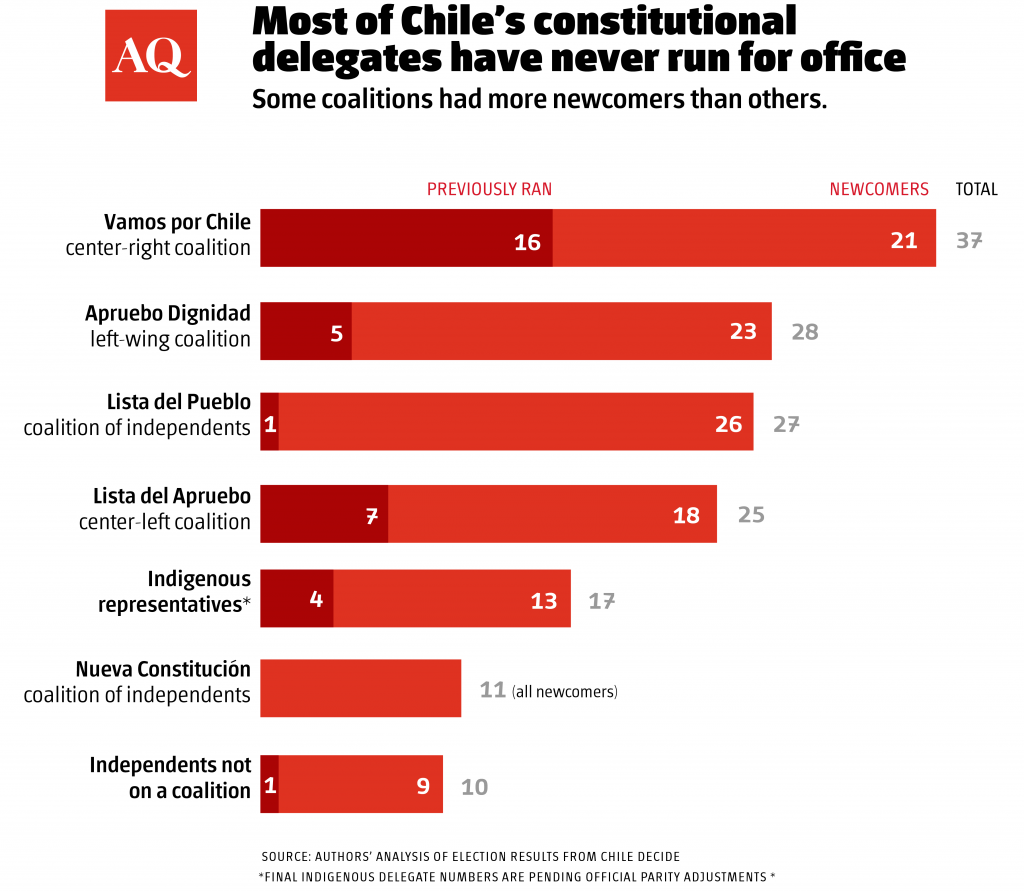

After elections on May 15 and 16, it’s clear Chileans will be getting just that. Our analysis for AQ found that of the 155 delegates chosen to draft Chile’s new constitution, only 34, or 22%, had ever run for elected office, and only 20, or 12.9%, had held elected office.

For many, the crop of newcomers raises hopes – and questions – about the kind of governing charter that will replace Chile’s dictatorship-era constitution.

New demands from new voices

Before the vote, feminists, Indigenous groups, students, leftists, pensioners, workers, and other groups had demanded that the constitutional convention reflect everyday Chileans. After months of negotiation, Congress agreed to more inclusive mechanisms, such as allowing independents unaffiliated with political parties to run, requiring gender parity among delegates elected in each district, and reserving 17 seats for Indigenous peoples.

In a country where just 23% of lawmakers in the lower house of Congress elected in 2017 were women – despite a 40% quota for female candidates – women were among the big winners of the election. The gender-balanced constitutional convention means putting women’s interests front-and-center. For instance, feminist organizations created the Platform for a Feminist and Multinational Constitution, which includes demands for environmental sustainability, social security for precarious workers, and an end to impunity for violence against women.

The call for a “multinational” constitution allies feminists with Indigenous peoples, who face pervasive marginalization in Chile. Few have ever held national elected office. The Indigenous Constitutional Platform, launched by a different collection of activists and politicians, calls for Indigenous peoples’ rights to territorial autonomy, language and culture, among other items.

Electoral newcomers

Our data show that it is not just delegates’ gender or ethnicity that bring a fresh perspective. It’s also that they are overwhelmingly newcomers to electoral politics. We matched the 1,468 convention candidates against a database of every person who sought or won elected office since Chile’s 1989 return to democracy, from municipal counselors to deputies and senators. The results: 82% of the candidates had never run for office before. The pattern translated into the results. Using Chile Decide’s list of winners, we concluded that 78% of delegates elected are first-time candidates.

Reserving seats for Indigenous candidates put 138 seats in play for the remaining candidates. Independents – who ran in coalitions or on their own – secured the lion’s share, winning 48 seats. Every one of them is a first-time officeholder. Together, they are a few seats shy of controlling one-third of the convention. This threshold matters, since any measure entered into the constitution needs approval from two-thirds of the delegates.

But independents do not necessarily speak with one voice. The traditional political parties will still play a role, though they too elected plenty of newcomers.

The newest coalition, the left-wing Apruebo Dignidad, took 28 seats, and only 18% of their delegates, or just 5 of 28, sought or held office previously.

The traditional center-left coalition Lista del Apruebo came in behind Apruebo Dignidad, at 25 seats – but the results are considered devastating for the alliance that elected most of Chile’s post-authoritarian presidents, including socialist Michelle Bachelet. Lista del Apruebo’s delegation is also less new than Apruebo Dignidad’s, with 28% of its delegates, or 7 of its 25, having sought or held office previously. Apruebo Dignidad is also nearly all men.

The award for nostalgia goes to the right-wing coalition Vamos por Chile, however: 43% of its delegates have run for office at least once before and 57% of its delegates are men. Some of these experienced delegates have political careers that started back in the early 1990s, making Vamos por Chile the delegation with the most establishment politicians.

Yet looking like the past is not necessarily an advantage, and Vamos por Chile underperformed overall. Observers had predicted that President Sebastián Piñera’s coalition would win enough seats to play kingmaker in the convention, but in the end, Vamos por Chile won just 37 spots, far short of the one-third that would give them veto power.

Overall the traditional coalitions like Lista del Apruebo and Vamos por Chile performed poorly while electing more veteran figures. Since there were no real differences in the proportion of newcomers that each coalition ran, the decision was left to the voters. It is not surprising that voters on the right especially opted for more experienced candidates, given Vamos por Chile’s emphasis on maintaining the status quo.

A new start

The composition of the constitutional convention carries forth protesters’ vision to erase the final vestiges of the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. With no one group or traditional coalition controlling the coveted two-thirds majority, the convention creates opportunities for new visions advanced by new alliances. Civil society groups have delivered their proposals to the delegates – as with the feminist and Indigenous constitutional platforms – and delegates will need to cooperate to reach agreement on the final text.

The overall newness of the delegates lends the constitutional process legitimacy in the eyes of those seeking a more inclusive Chile. And for the delegates, the hard work of earning voters’ trust is just beginning.

—

Piscopo is associate professor of politics and affiliate faculty of Latino/a and Latin American Studies at Occidental College and a leading expert on women and electoral politics.

Siavelis is a professor of politics and international affairs at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, NC, and has published widely on Chilean politics.