This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Guatemala.

SANTIAGO — As China’s AI dark horse DeepSeek was trampling U.S. tech stocks in late January, this corner of South America lit up. “I think it’s phenomenal,” said David Laroze, a Chilean physicist who heads up a $10 million supercomputing project in the Atacama Desert. “The more competition there is, the more widespread these language models become, the more we can learn and improve.”

Beyond its expanding number of data centers, Chile has new AI initiatives, large language models (LLMs), and subsea fiber-optic cables on the horizon. Late former President Sebastián Piñera planted the seeds of Chile’s tech ambitions during his second term (2018-22) by digitalizing government bureaucracy and introducing a national AI strategy. Piñera’s successor, current President Gabriel Boric, took up the baton with updated AI regulations, state funding, and regional cooperation. In the backdrop are innovation platforms such as Start-Up Chile, which have generated local successes like Notco, the country’s first billion-dollar startup that uses AI to develop plant-based foods.

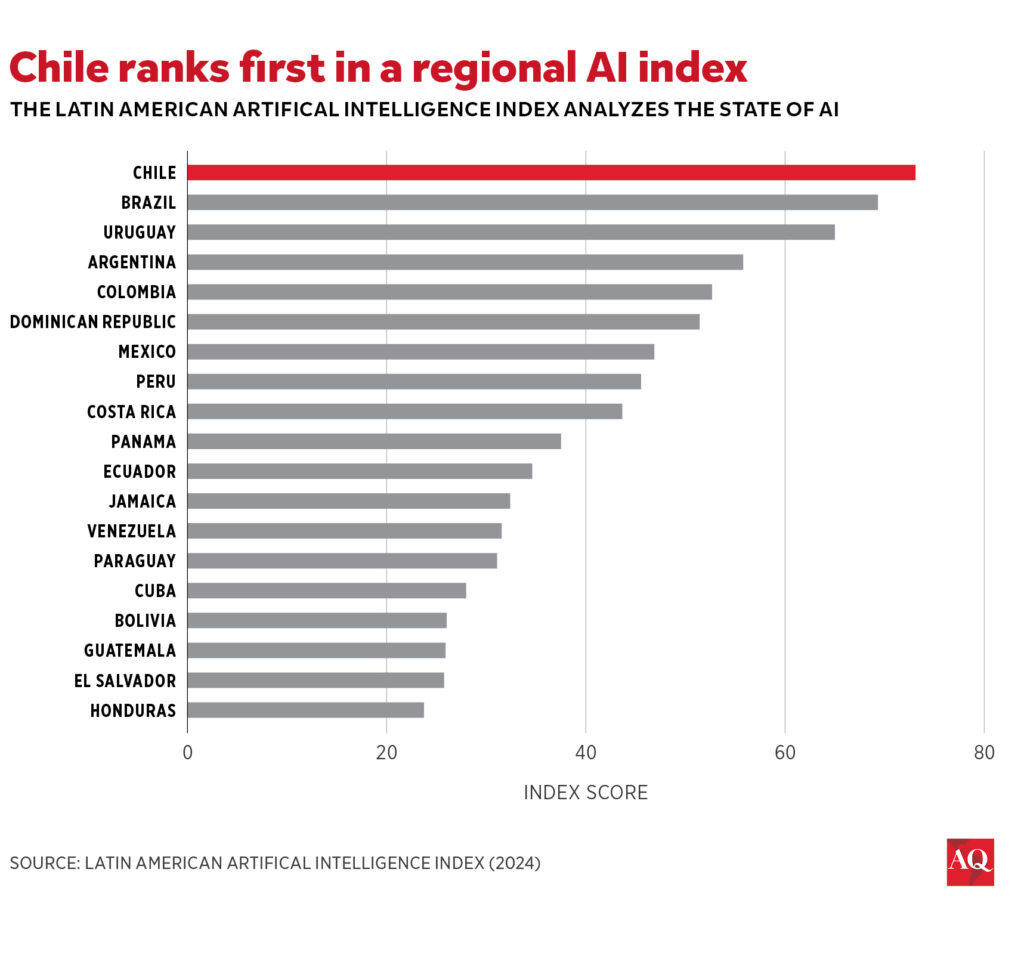

In the second Latin American AI Index, issued last year, Chile ranked first among 19 countries in the region in advancing its AI ecosystem, just ahead of Brazil. And in certain fields, Chile has a world-class edge in gathering the data streams needed to train AI models. Astrophysics is a prime example, Laroze said. With the imminent launch of the U.S.-funded Rubin Observatory followed by Europe’s Extremely Large Telescope in 2030, northern Chile will concentrate 70% of the world’s astronomical observation capacity.

Just before a trip to California to court Big Tech late last year, Science Minister Aisén Etcheverry touted Chile’s open trade policy for attracting a diverse portfolio of tech investors that transcends geopolitical tensions. “We’ve been able to partner qualitatively and commercially with basically everyone,” Etcheverry told AQ. “And even though we’re in a complicated world, that policy hasn’t changed.”

Chile and the AI race

For countries Like Chile that are striving to achieve “digital sovereignty,” the AI race is less about gaining geopolitical advantage than accessing technology. And China’s AI breakthrough just lowered the threshold. Defying U.S. export controls that were meant to check Beijing’s AI progress, DeepSeek offers an open-source model that it claims was substantially cheaper to develop than peers rolled out by U.S. titans like OpenAI and Google. With the notable exception of Meta’s Llama chatbot, the inner workings of the cutting-edge U.S. AI models are under wraps.

The chance for software engineers to tinker under DeepSeek’s hood is encouraging to Álvaro Soto, director of Chile’s National AI Center (Cenia), which is collaborating with neighboring countries to develop LatamGPT, an LLM for Latin America and the Caribbean. DeepSeek “validates what we’re doing,” he told AQ. “Before, someone might ask, ‘What are you doing? You need infrastructure. You’re too far away, don’t bother.’ So for something intermediate to come out, it shows what can be done.”

Still, compared to Europe, East Asia and North America, Latin America remains a laggard. Chile ranks 44th worldwide in Oxford Insights’ Government AI Readiness Index, which pegs Brazil as the regional leader.

Chile’s pioneer was the National Laboratory for High Performance Computing, born out of the University of Chile’s Center for Mathematical Modeling in 2011. Yet more powerful systems will be housed at the future National Compute Center in the northern city of Arica, where the Universidad de Tarapacá’s Instituto de Alta Investigación, headed by Laroze, recently procured H200 semiconductors from U.S. behemoth Nvidia. Another batch of chips could be deployed under a $7 million tender from Chile’s development agency Corfo.

Such outlays are dwarfed by colossal supercomputing ventures such as the new $500 billion Stargate initiative in the U.S., led by Japan’s Softbank and OpenAI. Closer to home, Brazil has committed $4 billion to AI and supercomputing.

Laroze is undaunted. Big investments “might revolutionize the world. But on a smaller scale, one can make smaller revolutions that are important, too.” AI could enable Chile to grow more resilient crops, manufacture stronger industrial materials, improve climate forecasts and even mitigate local traffic.

Soto is less sanguine. Unless it commits more resources to AI, Chile risks falling behind, he said. “We won’t see results tomorrow, but we need vision.”

Data center surge

Latin America’s AI lag is belied by surging construction of new data centers. Chile currently has 33 in operation. Most are retail data centers that offer short-term leases to multiple clients, but a growing number are larger, more energy-intensive colocation facilities apt for AI. According to a recent Colliers report, another 34 greenfield data centers or expansions are in the pipeline, exceeding the government’s 2030 target.

Data centers gobble up energy, so their proliferation in places like Texas encourages planet-warming gas power generation and weakens decarbonization efforts. In contrast, Chile abounds in renewable solar and wind energy. In Google’s portfolio, Chile is the greenest data center jurisdiction in the Global South, with 91% of round-the-clock energy coming from carbon-free sources, just ahead of Brazil at 90%.

Even so, like in many places, permitting for new data centers is a challenge. Pending legislation to streamline Chile’s notoriously slow environmental evaluation process should help. But on a local level, communities worried about scarce resources are pushing back. Last year, Google withdrew a permit application for a second data center in Santiago after residents protested over water usage.

Concerns over water supplies are well-founded. Although abundant precipitation last winter provided some respite after 15 years of drought, Chile is drier than it used to be. Data center developers maintain that their installations don’t aggravate the scarcity. The centers already recycle water, and new technologies would use other liquids or outside air for cooling, said Francisco Basoalto, the Equinix Chile CEO who heads the Chilean association of data centers, a new lobbying group that is challenging what it describes as “myths” that are driving local opposition.

Google’s plan to submit a revised proposal for a new data center that will use air cooling instead of water will test local sentiment. Other tech companies on Chile’s digital map, including U.S. firms AWS, Oracle, and Equinix, as well as China’s Huawei, are monitoring Google’s progress.

Looking beyond its borders, Chile hosts a growing number of subsea fiber-optic cables that make digital architecture more robust. Google runs the Curie cable connecting Chile to California, with a branch to Panama. The U.S. giant is now in the final stage of negotiations with the government to build the trans-Pacific Humboldt cable that will run 12,000 kilometers, from Chile through French Polynesia to Australia. Another new cable will connect the mainland of southern Chile to Antarctica.

Chile’s tech ambitions have become embedded in state policy, laying the foundation for the country to become a digital champion for Latin America. Yet for all of its progress, Laroze worries that without more investment in early education, not all Chileans are equipped for the rapidly advancing digital age. “Moving the frontier of knowledge is not done only through infrastructure. It’s done through critical thinking.”