Last November, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines made waves when it received an oil shipment from Venezuela—its first since 2019. In doing so, the island country became the first to resume ties under Petrocaribe, the agreement struck by Hugo Chávez that saw Venezuela send oil on generous terms to 17 Caribbean nations.

Analysts agree there’s little chance of a full-scale revival of the accord, which fell apart after Venezuelan oil production plummeted in the mid-2010s and the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, OFAC, imposed sanctions in early 2019 on Petróleos de Venezuela SA, the nation’s state-owned company known as PDVSA.

Countries “need to go to OFAC and get a license in order to interact with Venezuela,” according to Luis Pacheco, who was chairman of the ad-hoc administrative board of PDVSA from 2019 to 2020. The alternative to acquiring a sanctions exemption is using expensive, often shady middlemen who “re-flag ships” from a third-party destination like Cuba—the strategy taken by Saint Vincent.

But these obstacles haven’t stopped demands for Petrocaribe’s return from a growing group of Caribbean leaders earlier this year, from regional bloc CARICOM to Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley, who made a state visit to Caracas last month.

What explains the interest in this moribund arrangement? Behind recent calls for Petrocaribe’s return are the Caribbean’s flawed, oil-dependent energy sector, serious obstacles that have prevented its transition to alternative, cleaner sources of power—and a lack of meaningful assistance from the U.S. that could have geopolitical repercussions in years to come.

Petrocaribe’s legacy

Petrocaribe was first established by Chávez in 2005, offering a “power now, pay later” model. Member states, largely island nations reeling from costly fossil fuel imports, paid up to 60% of the value of oil shipments from Venezuela, leaving the remainder to be repaid over decades at low interest rates. The agreement was billed by Chávez as a pathway to development; it effectively eliminated the cost of oil imports, granting governments previously unthinkable leeway to invest in infrastructure and services.

In return, Venezuela received a network of allies in the Caribbean and often exerted its influence to garner support at international fora. Every Petrocaribe member except Honduras voted to bar opposition leader María Corina Machado from presenting before the Organization of American States, OAS, in 2014. Saint Vincent and Dominica’s votes helped prevent Venezuela’s suspension from the OAS in 2018. “That’s what it always was—buying political support,” Pacheco said. Petrocaribe was more than just a collection of oil customers for the Venezuelan government: It was a security ring vital to insulating the regime from international isolation.

The mutual benefits of Petrocaribe eroded by the mid-2010s. Funds were routinely mismanaged by corrupt actors (sometimes catastrophically) and tensions arose when debt repayment finally reared its head. Petrocaribe began to disintegrate after PDVSA’s production fell by nearly half in the mid-2010s, and Caracas could no longer justify the hefty deficit generated by the agreement. The accord was rendered defunct after U.S. sanctions were imposed in early 2019, forcing Caribbean states to return to the international oil market.

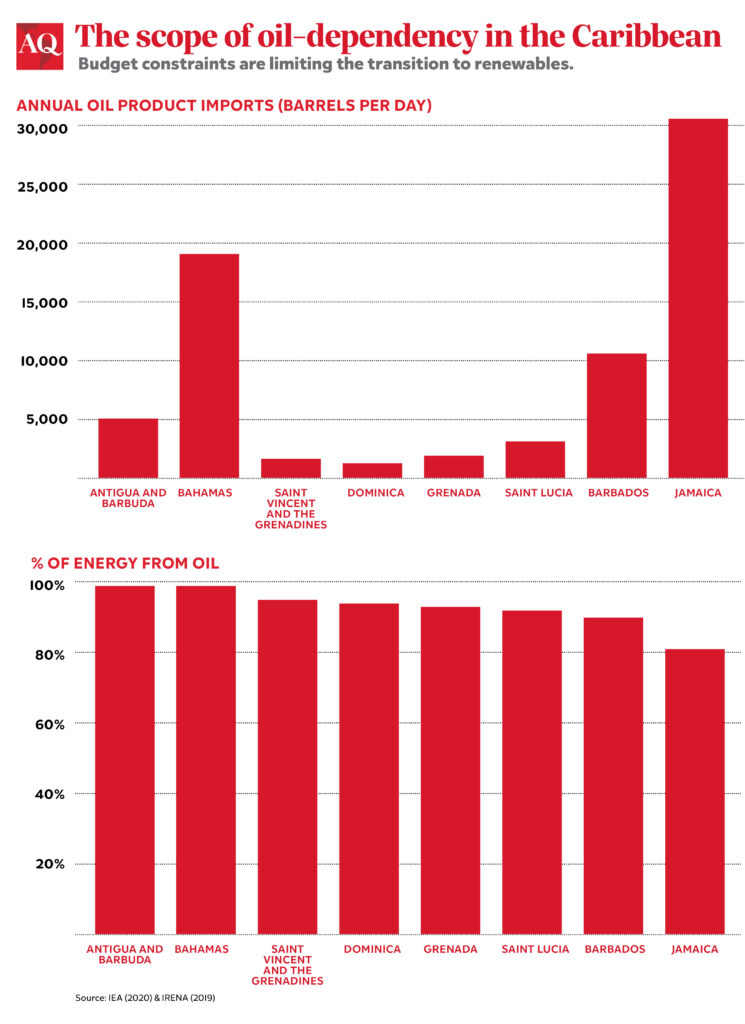

In addition to long-term debt, Petrocaribe left the Caribbean with a hyper-dependency on foreign oil imports. Its initial affordability led many countries to double down on existing oil-dependent infrastructure, perpetuating demand. Saint Vincent, for example, relied on oil for 95% of its total energy supply in 2019.

The Caribbean’s energy dilemma

With heavy dependency on oil and high vulnerability to natural disasters, the transition to renewable and resilient energy systems is a major priority in the Caribbean. Yet despite the options available, the region has so far made slow progress.

“The biggest barrier is economies of scale” for the energy transition, said Thomas O’Keefe, president of Mercosur Consulting Group. New infrastructure is costly, and Caribbean nations have spent huge sums on fuel subsidies and debt repayment for oil imports, preventing investments in less expensive long-term energy solutions.

Compounding the region’s energy dilemma is the inability to secure financing for new energy infrastructure. Considered middle-income, most Caribbean countries can’t access funds reserved for developing nations, and their indebtedness makes them unattractive targets for international lenders.

Though various initiatives have aimed to address the energy financing dilemma, like the Bridgetown Initiative and PACC 2030, Caribbean leaders have been frustrated by the lack of action resulting from often-supportive rhetoric from key figures.

In the meantime, the region remains dependent on oil. And with electricity prices nearly twice those in continental Latin America, nations must seek the cheapest sources of fuel oil imports to stay afloat. In the absence of meaningful financing from the West, a return to Petrocaribe is an attractive prospect for cash-strapped governments.

The road ahead

However, “Petrocaribe is history,” O’Keefe said. Sanctions relief appears increasingly unlikely given the state of negotiations between Maduro and the Venezuelan opposition.

And despite a recent uptick in PDVSA’s oil output, “only about 40% of their production is used to create income—the rest goes to paying debt,” according to Pacheco.

So why is the Caribbean pushing for Petrocaribe’s revival in spite of the odds? As Pacheco put it, “beggars can’t be choosers.” The support that the idea of ‘Petrocaribe 2.0’ has garnered points to structural fiscal and energy needs in the Caribbean that demand to be addressed, and a lack of available means to address them. For the time being, the U.S. has done little in response to repeated calls to facilitate either of two possible futures for energy in the Caribbean—dramatically expanding green financing; or granting sanctions exemptions and permitting subsidized oil dependency.

As a result, Caribbean nations are likely to endure mounting struggles and fiscal strains in supplying their populations with energy, as well as setbacks in the attempt to transition their grids to green sources. As the energy dilemma has intensified, so have calls for Petrocaribe’s revival—whether that support translates into tangible solutions remains to be seen.

__

Quinn is an editorial assistant at AQ