SANTIAGO—Chile is stuck in the slow lane on lithium. President Gabriel Boric’s administration is hoping a roadmap introduced one year ago will steer the mineral-rich country onto a faster course by encouraging investment without compromising social and environmental commitments. A few investors are eager to jump in. But with state companies mandated to control the most coveted assets and legal clouds on the horizon, others are wary.

Lithium is among a handful of minerals critical for renewable energy and batteries used in electric vehicles, so Chile’s policy matters for the global transition away from fossil fuels. According to the International Energy Agency, appetite for lithium, copper, cobalt, nickel, graphite and rare earths will grow by up to 350% from 2022 to 2030. Nearly all lithium production is currently concentrated in Australia, Chile and China, and the latter dominates processing. A supply deficit could emerge as early as 2028.

Chile boasts a formidable resource base and a reliable record as a top copper producer. And according to experts, such as Universidad Católica professor Gustavo Lagos, it is cheaper to produce lithium in Chile than anywhere else. That means that Chile has a “much wider” window for production than other countries, once lithium recycling kicks in on a massive scale, Lagos wrote in a recent column in El Mercurio.

However, as Latin America’s oil map shows, underground resource wealth is not a guarantee of success. Above-ground conditions matter more.

After years of policy delays and a lithium price surge in 2022, former number-one producer Chile has lost market share to Australia, while others like Argentina are turning heads. Critics say the new state-led strategy will do little to change that.

A key drag is resource nationalism. “This is like the bully who goes home with the ball. The government took the best areas and left the rest for everyone else,” Daniel Jimenez, partner at Santiago-based consultancy iLiMarkets, told AQ. Moreover, “Chile missed a wave of strong lithium prices that probably won’t come back.”

Chile’s lithium is tucked into more than 60 salt flats that dot the mountains of the northern Atacama Desert. Only two companies currently produce lithium in the country: Chilean firm Sociedad Química y Minera (SQM), whose second-largest shareholder is China’s Tianqi, and U.S. competitor Albemarle. Both extract brine-based lithium from the vast Atacama salt flat, considered Chile’s crown jewel. Other companies hold mining concessions and have conducted studies in anticipation of securing lithium contracts.

In April 2023, Boric unveiled the new strategy allowing SQM’s lucrative Atacama leases to be extended if state-owned copper mining company Codelco controls future operations. Last December, the two firms signed a memorandum of understanding to operate jointly from 2025 to 2030, after which Codelco will control the operations through 2060. Albemarle’s contract expires in 2043.

Maricunga is the second “strategic” salt flat designated for control by Codelco. In five others, Codelco and small state minerals company Enami will work with private-sector partners. Another 26 salt flats will be fully open to private investors. Others will be set aside for conservation.

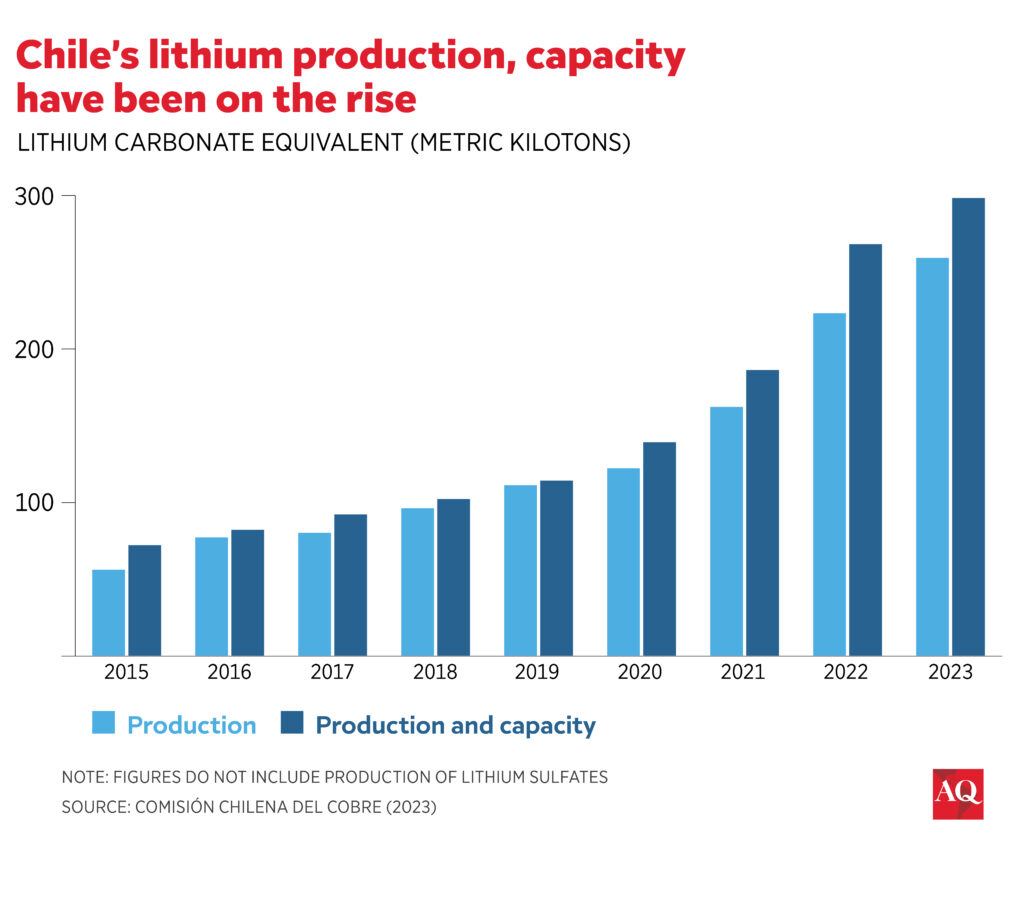

“There is room for everyone,” Finance Minister Mario Marcel said last month when further policy details were announced. The administration projects that annual production of lithium carbonate equivalent will double in 10 years using more efficient and environmentally-friendly technologies.

Such goals could prove elusive as long as Codelco is in charge, critics say. The government was “irresponsible” in entrusting Codelco because the company has neither the experience nor the human capital to do this right, says Universidad Mayor economics professor Carlos Gomez. He suspects lithium revenues will be diverted to cover its debts, an assertion the government and Codelco have denied.

Former energy and mining minister Juan Carlos Jobet shares the skepticism. On a wider level, he blames Chile’s byzantine mining legislation. “There is no political will to fix it,” he told AQ.

A strategic resource

Unlike its other main minerals, Chile does not allow concessions for lithium. The prohibition dates to 1979, when the military dictatorship deemed lithium a strategic resource because it was believed to have nuclear applications. That turned out to be untrue, but the “strategic” label endured. Today, incumbent companies hold concessions to extract other minerals in the salt flats, so it’s not clear how those rights will be reconciled with future lithium contracts if different companies secure them. The status of legacy pre-1979 rights is also uncertain. This ambiguity is bound to spark court battles, Jimenez and Jobet say. The administration is quietly hoping the companies will choose to negotiate rather than litigate.

Among the newest concession holders is Eramat. Last year, the French company acquired rights to salt flats, including the promising La Isla, which the government has assigned Enami to participate in. Eramat executives told Diario Financiero the company could invest $800 million to $1 billion to produce 25,000 metric tons per year of lithium carbonate from multiple salt flats.

Another contender is Chilean start-up CleanTech Lithium, which hopes to secure contracts in as little as four months for its Laguna Verde and Francisco Basin assets. The company has already consulted local communities and built a lithium pilot plant, and plans to begin supply negotiations with potential buyers in September. “We’ve done $25 million in investment already,” CEO Aldo Boitano told AQ. “We invested in times when people wanted more clarity. We bet that the government would come forward.”

Investors are now waiting for the mining ministry to issue a request for information to determine where it will consider awarding contracts via tenders and, possibly, direct negotiations with incumbents.

Requisite consultations with Indigenous communities will be carried out before contracts are awarded, the government says. Some communities are already on board, while others want to ensure that already scarce water supplies won’t be further depleted. Investors are hoping the government fulfills a pledge to streamline environmental permitting, which can take years. Already, parts of Boric’s own constituency are pushing back against the administration’s lithium strategy for promoting “extractivism” and “eco-colonialism” by foreign companies.

Across the Andes, Argentina could have up to a dozen lithium projects—many Chinese—running in two years, Jimenez says. Argentina’s federal system gives provincial governments more leeway to strike deals, and M&A activity is picking up. The country is dogged by macroeconomic distortions and political uncertainty, but investor confidence is slowly recovering under pro-business President Javier Milei. In Bolivia, the third leg of South America’s lithium triangle, economic and geological conditions are considered less favorable.

Unlike Bolivia and Argentina, Chile has a free trade agreement with the United States, giving it a commercial advantage under the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act that prioritizes imports from FTA partners. Chile also has a newly minted modernized trade deal with the European Union.

The Boric administration denies that Chile has fallen behind on lithium. “We’re not arriving late. We’re arriving well,” says Karla Flores, director of investment promotion agency InvestChile, adding that companies value Chile’s slow and steady approach that emphasizes social and environmental sustainability.

That view seems optimistic. Some lithium contracts will probably be signed before Boric’s term is up in early 2026, but it may be up to his successor to shift lithium into a higher gear.

Boitano is encouraging Chile to move swiftly. “If we don’t do this, the world will find another way.”