This article is part of AQ’s special report on Lula and Latin America and was adapted from “Comércio e gênero: uma abordagem diplomática,” published online as a Snapshot in CEBRI-Revista (Apr-Jun).

Gender equality has clear social, economic, and political benefits, but governments and market structures continue to perpetuate inequality nonetheless. In Brazil, where domestic policies, including Bolsa Familia, address this issue by empowering women, the same is not fully reflected yet in its foreign service representation. And a feminist foreign policy would not only legitimize the Brazilian government’s gender parity initiatives—it would expand its trade horizons, benefitting the entire economy.

In Brazil, the diplomatic service, best known as Itamaraty, has been trying to align itself with gender policies. In 2023, for the first time in its history, a woman holds the post of foreign affairs vice minister—the second-highest job within the diplomatic service. The role of high commissioner for gender issues was also created, and today we have women leading three of the 10 Itamaraty secretariats in Brasília. This 30% rate of representation is also a historic high.

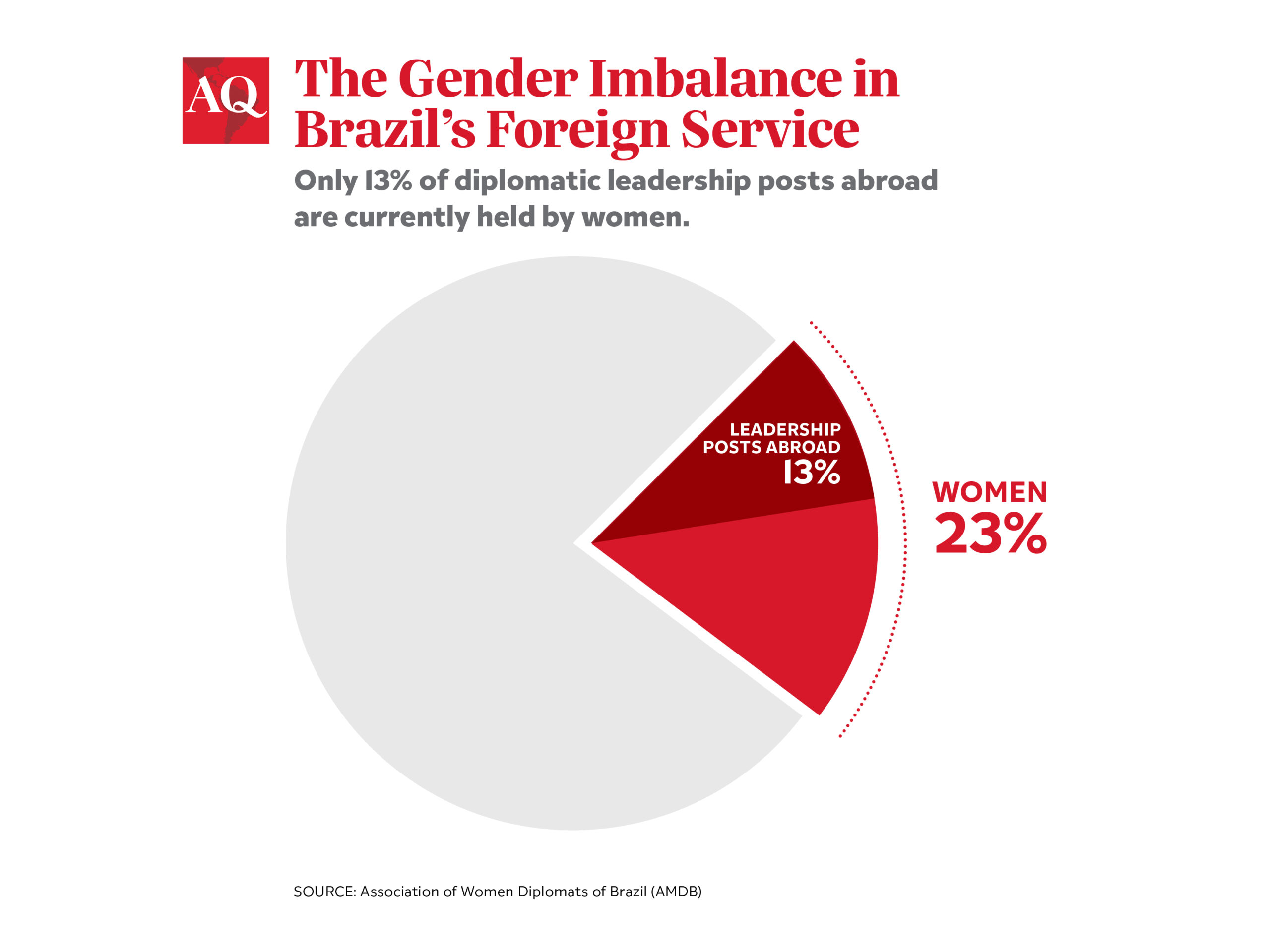

Nonetheless, we have a lot to improve. Brazil and Uruguay are the only South American countries that never had women as foreign relations ministers. Brazil has the lowest percentage of women in diplomacy among Mercosur countries: While 23% of Brazilian diplomats are female, they hold only 13% of all leadership foreign posts abroad. This despite having highly qualified candidates: At the top of the career, 20.5% of first class ministers and 19.5% of second class ministers are women that could occupy leadership positions abroad. That is why in January 2023, an informal group that had been active since 2013 decided to formalize their advocacy by creating the Brazilian Association of Women Diplomats with the goal to make gender parity at the nation’s foreign service a formal state policy.

A Trade Multiplier

Public policies related to gender depend necessarily on the presence of women in the public sector. This is not different in the case of trade and regional agreements. Governments have a critical role in leading on this topic, which requires promoting gender equality in all spheres of the decision-making process.

Having women at the table during trade negotiations is of fundamental importance for all countries. Today, Germany and Canada’s diplomatic missions follow a gender parity policy. The UK has nominated only women to head its embassies in UN Security Council member countries. The French foreign service is openly feminist, with a high commissioner for equality and full gender parity both in internal positions as well as in diplomatic missions abroad.

In December 2017, the World Trade Organization (WTO) adopted the Buenos Aires Declaration About Trade and Economic Empowerment of Women. The declaration specifically calls for an increase in the presence of women in international trade—a novelty since, up to then, similar declarations would be restricted to human rights. Today, 127 of the 164 WTO members have signed the Buenos Aires Declaration, and the number of trade agreements that include specific language about the women empowerment and inclusion increased from 74 treaties in 2018 (25% of the total 292 agreements) to 83 treaties by 2021.

A large part of those clauses and chapters are still considered “soft law.” They recognize that it is more difficult for women-led companies to access credit and export mechanisms, something underscored by studies published in Brazil by the Export Promotion Agency (APEX) and the Trade Ministry that show the hard reality presented for women in trade. The data shows that exporting allows women-led companies to increase their revenue, hire more women, and have a positive multiplier effect on the entire economy. Then, if the gender perspective in trade is such a rational decision, economically and politically, why do so few countries have commitments about the topic? And why are they mostly not mandatory?

A feminist foreign policy starts by increasing the number of women in the foreign service, nominating them to positions of power, and incorporating the gender perspective into foreign affairs comprehensively. At the moment, Brazil does not have a feminist external policy yet. This, together with the deficit of female representation in the high echelons of the foreign service, has a profound impact on Brazil’s overall foreign policy. (Guatemala is the only other country in Latin America where female participation in the public office sits below 20%.) One of these impacts is the paltry presence of gender commitments in trade agreements signed by the country. Brazil does have a gender chapter on its trade agreement with Chile and, with fellow Mercosur nations, is finalizing a similar negotiation with Canada. But the chapter included in the Chile accord is non-binding and outside the dispute negotiation mechanism. Stronger clauses can be found in the trade agreements negotiated between Canada and Chile, for example, which includes specific targets for cooperation in female leadership, financial inclusion, participation in science and technology, as well as a more robust Gender and Trade Committee. The Chile-Brazil agreement has a committee as well, but it is not as structured as the one in Chile-Canada.

There is a close relationship between the adoption of feminist foreign policies and the strengthening of gender clauses in trade agreements. In the case of Chile, the discussion about the country’s feminist foreign policy was reflected in the adoption of gender clauses in its trade agreements. Canada, since 2017, adopted the Feminist International Assistance Policy, which has deepened the use of gender clauses in the agreements negotiated by the country. In 2020 Canada, Chile, and New Zealand signed the Global Trade and Gender Agreement (GTAGA). In 2022, Mexico, Colombia, and Peru joined the agreement that established mechanisms to support exports by women-led companies.

The adoption of a feminist foreign policy by Brazil would strengthen the government’s initiatives on gender parity in the domestic agenda and apply a gender lens to all initiatives on the external front in a comprehensive way. On the commercial front, this new perspective would help include and prioritize clauses that consider gender implications in trade and economic agreements with practical applications, such as the capacity to stimulate exports by women-led companies, expanding the gains to the whole of society. Following successful domestic policies that take gender into account, such as Bolsa Família, the time has come for Brazil to adopt a feminist foreign policy and collect the fruits of an inclusive foreign trade.

—

*The authors are founding members of the Brazilian Association of Women Diplomats (AMDB).

**This article reflects the opinion of the Brazilian Association of Women Diplomats (AMDB) and does not necessarily represent the official positions of Itamaraty.

Leal is a diplomat, holds a law degree from the Universidade Estadual da Paraiba, and has served at the Brazilian embassy in Santiago, Chile.

Paranhos is a diplomat with a law degree and a master’s degree in diplomacy from Instituto Rio Branco. She has worked with Mercosur trade issues, dispute settlement at the WTO and intellectual property at WIPO.

Aquino Bonomo is a diplomat currently serving as Deputy Consul-General of Brazil in London. She holds a law degree, a master’s in diplomacy from Instituto Rio Branco, an MBA from the University of Bridgeport, and executive courses at several prestigious universities. She has served at CAMEX and led the trade sector of Brazil’s Embassy in Washington, DC, among other posts.