This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on transnational organized crime.

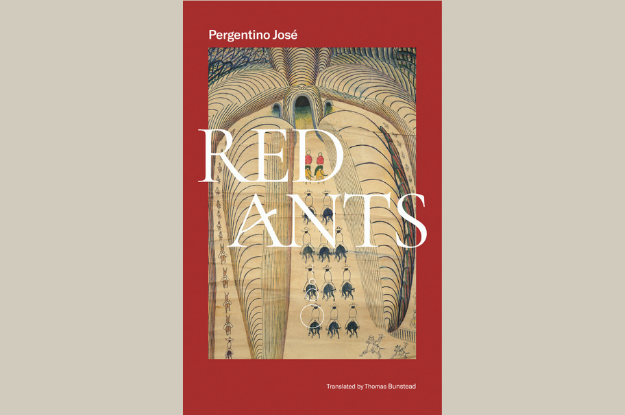

In his first short story collection, Red Ants, Zapotec writer Pergentino José blends magical realism with the mythology of his upbringing to shine a light on the historical struggles of Mexico’s indigenous communities — and to make clear that the threats they face have not gone away.

The title of the collection is a nod to the primary theme of José’s stories: In Zapotec culture yellow ants represent happiness and good fortune while red ants represent adversity. José’s tales are thus full of everyday violence and hardship that stem from a community being forced to assimilate and leave behind its way of life.

In “Room of Worms,” José’s narrator sees a forest torn down by his own community to help an absentee landlord establish a coffee plantation, all while birds noisily escape the area. In Zapotec tradition, the forest is where many spiritual rituals take place, and birds represent the divine. Here is José’s lament for the loss of tradition and a fractured spiritual life, as Zapotec communities are forced to abandon their customs. In the narrator’s inhospitable shelter full of worms and roaches falling from the roof, a friend ominously tells him, “Nza nja mend tub do nit to? Can you hold back the sea? The bridge of dreams broke, but this world does not belong to you.”

Other of José’s stories allude to the role of the Catholic Church in indigenous life. Beyond introducing a foreign belief system that was adopted by many Zapotecs after the conquest, in José’s telling the Church has continued as a form of institutional control over communities like his. In “Prayers,” a man walks through a dystopian town that is ruled by the dictatorial Padre Edgardo, a priest who uses physical violence and guards to control the townspeople and impose his own zealous religiosity.

“Voice of the Firefly” tells of suffering with the introduction of foreign diseases. The narrator loses his wife to smallpox because the town’s nearest doctor neglected to quickly offer help. The doctor’s cruel demeanor maddens him and leads the narrator to kill the doctor in broad daylight, only to be tormented by his actions. José’s surreal imagery comes to life in the narrator’s fears of turning into a firefly, destined to die if he leaves his house.

The common thread across the book’s 17 stories is the metaphorical presence of red ants, tied to each narrator’s distress and, in some cases, the fruitless search for a return to the way things were. Along the way, José paints a picture of the richness of Zapotec culture. His dreamlike settings and open-ended writing leave ample room for interpretation. But it becomes clear his are traditions in need of protecting.

José has said that the main goal of his writing is to “rescue the collective memory” of his community, the proud “people of the clouds,” as Zapotecs refer to themselves. In Red Ants he succeeds in taking readers to a different world, one that they did not expect but will be unlikely to forget.

—

Reina is an editor and the business and production manager at AQ