It wasn’t long ago that Marcelo Montenegro was still the toast of the town.

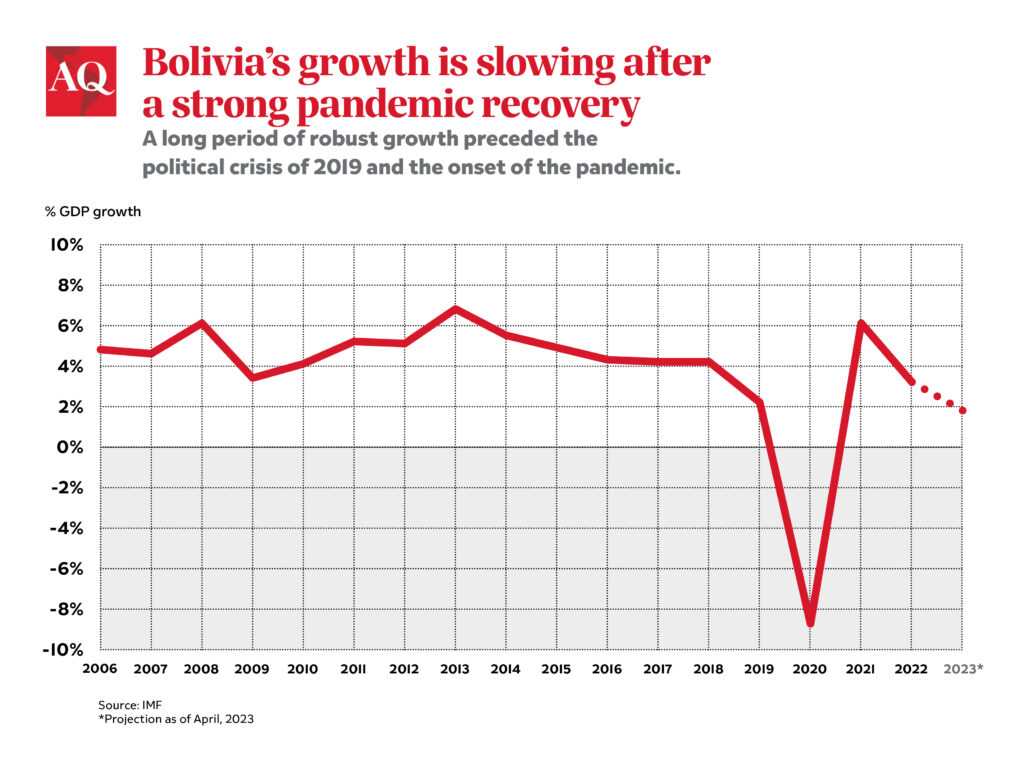

In January, The Banker, a storied international publication, named Montenegro its 2023 “Finance Minister of the Year” for the Americas, citing Bolivia’s “faster than expected” economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and inflation of just 2.6%, one of the lowest rates in the world. It was the latest accolade for a country that over the past 17 years of mostly leftist rule sometimes seemed to defy gravity, combining unorthodox policies like nationalizations with economic growth above 4% and an extreme poverty rate that fell by half.

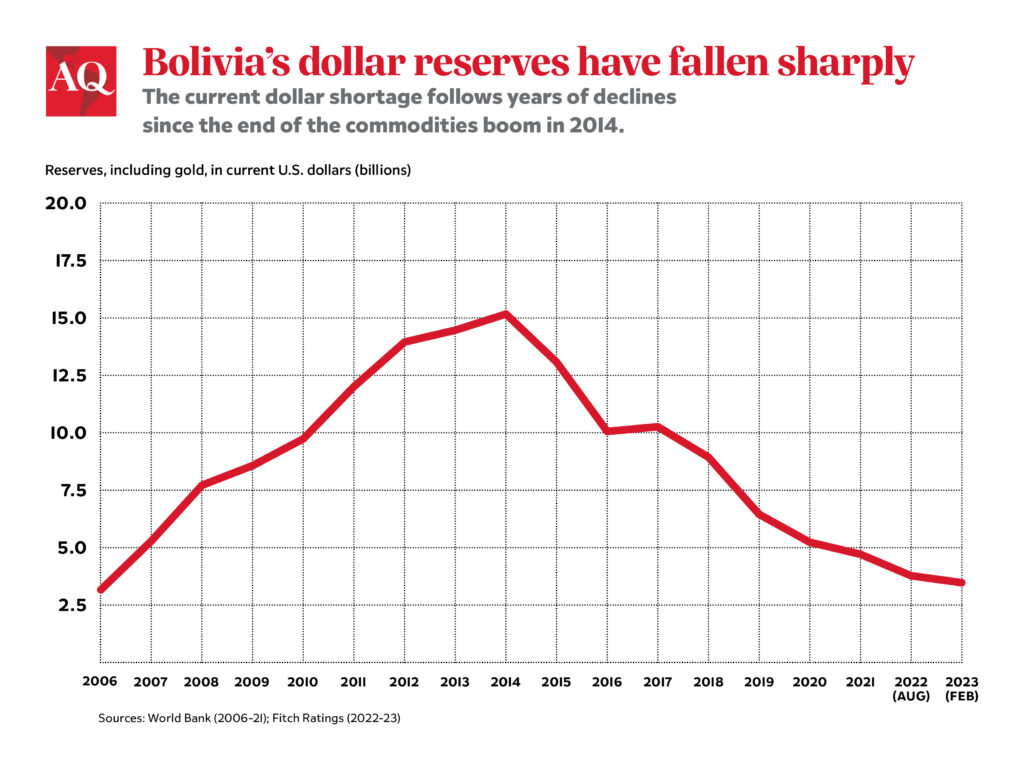

But more recently, both Bolivia and its charismatic finance minister have come crashing back to earth. Confidence in the financial system cratered, leading Bolivians to line up at banks to withdraw money. The country’s central bank (BCB) stopped publishing data on its dollar reserves in February, after announcing that only $3.5 billion remained from a 2014 peak of $15.5 billion. Some fear an even bigger economic collapse is around the corner.

Analysts describe a story of macroeconomic fundamentals and a years-long lack of investment finally catching up with Bolivia—but also of a government that seemed to believe its own hype and lost credibility, making the crisis even worse.

When Montenegro joined the Finance Ministry in 2020, he reinstated the heterodox economic model developed under President Evo Morales (2006-19), which nationalized natural resources like oil, gas and lithium, while using public investment and redistributive programs to reduce poverty and stimulate domestic demand. The approach appeared to pay dividends during the pandemic, which saw Bolivia’s economy grow 6.1% in 2021 and 3.2% percent in 2022.

Montenegro, a 50-year-old civil servant who had previously been president of Bolivia’s development bank, was an especially enthusiastic salesman. In frequent media appearances, he paired cogent economic analysis with a laid-back, informal way of speaking marked by a strong La Paz-paceño accent. “In recent memory, we’ve never had an economy minister who was so extroverted, who communicated so much,” Oscar Zegada, an economist at Cochabamba University, told AQ.

But credit rating agencies that have since downgraded Bolivia say its problems were a long time coming. The government depleted its dollar reserves by maintaining fuel subsidies and continuing to defend the boliviano’s pegged exchange rate to the dollar, even after years of declining gas exports had reduced foreign exchange inflows. Once a gas-export giant, Bolivia became a net importer of fossil fuels in 2022 due to lack of investment and increasing domestic demand. Analysts became particularly alarmed about Bolivia after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine raised energy prices and climbing U.S. interest rates made international borrowing more challenging.

As Bolivia’s outflow of dollar reserves accelerated, Montenegro embraced shallower messaging and softball interviews that often sounded more like empty boosterism for the government of President Luis Arce, Zegada said.

“These days, those who interview Montenegro tend to be the people who interview Miss Bolivia contestants or famous footballers,” he said. “This undermines trust, and causes people to see the minister as a kind of propagandist.”

“In a way, he became more of a spokesperson than a policy leader,” said Diego von Vacano, a professor of political science at Texas A&M University who advised the Arce government on economic matters from 2019-22.

Montenegro and other Bolivian authorities have tried to downplay the dollar shortage as a temporary result of unnecessary speculation, and even attacked their critics. In February, Montenegro accused concerned analysts of stoking “fear in the population” and irresponsibly fueling the problem.

But that didn’t work. “Montenegro was saying everything was perfect when all the measures were going the other way,” said Sebastián Fernández, an Andean region analyst at Control Risks. “That drives speculative behavior.” Montenegro and his ministry could have softened the rush for dollars had they instead admitted the problem and announced concrete steps to address it, Fernández told AQ.

Montenegro also could have blunted the crisis by coordinating better with other ministries and working to boost lagging investment in gas and lithium, von Vacano told AQ. Bolivia has the world’s largest proven reserves of lithium, and in 2006 the government announced plans to develop them through state enterprises. The government has since poured $800 million into lithium extraction through evaporation, but this method has underperformed and produced little. Under Arce, state lithium company YLB finally announced it was looking for foreign partners to invest in new methods, but waited until this January to ink a major contract—a $1 billion agreement with a Chinese consortium.

Von Vacano added that Montenegro was in meetings on a proposal from U.S. economist Joseph Stiglitz to develop green bond financing, another potential source of dollars, “but it simply wasn’t taken up.”

Through a spokesperson, Montenegro declined to comment for this article.

Alejandro Bilbao La Vieja Ruiz, a consultant and career diplomat who was most recently the Arce administration’s chargé d’affaires in Washington, said the Finance Ministry has a long list of recent accomplishments to be proud of, including the rollout of new social programs. He added that Bolivia regularly beats International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank growth projections.

However, he also said the ministry’s lack of initiative delayed the passage of a key bill: the “Ley de Oro,” which would allow the BCB to liquidate some of its $2.6 billion in gold to shore up reserves, as well as buy gold directly from local producers. Congress finally passed the bill on May 5 after it had languished in the legislature since June 2021.

“Given the bill’s importance, all the elapsed time since they first submitted it to Congress brought unnecessary hazards,” Bilbao told AQ, saying that Montenegro and the Finance Ministry could have stressed the bill’s urgency to get it passed it earlier.

Now that Montenegro has admitted the dollar shortage is a problem, he has been able to push short-term fixes that have improved confidence somewhat, Fernández said. “He’s done better trying to put the problem in context and saying these are the solutions we can move forward on.” These potential solutions include new credit lines from the CAF Development Bank of Latin America, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Japanese International Cooperation Agency, and elsewhere, along with the “Ley de Oro” and new action to encourage investment in the energy and lithium sectors.

Nevertheless, the IMF projects that growth will slow to 1.8% this year and unemployment will continue to tick up, reaching 5% in 2024 for just the third time since 2007. And it remains to be seen whether Montenegro will admit adjustments are necessary on either of the two underlying drivers of the crisis: the fuel subsidies and the currency peg. If they aren’t addressed, some analysts fear a crash.

“It’s not about saying we’re doomed,” Fernández said. “It’s about stating the problem and framing solutions to build confidence.”