Bogotá residents joke about the years they’ve been waiting to finally have a metro railway system. The news website Infobae has called it el metro que no lleva ni un metro (the metro system not even a meter long). “The Bogotá metro project has advanced, and we are already in 1999,” announced the Colombian online publication La Silla Vacía in 2013.

It’s a surprising absence in a city of 8.3 million people. Even smaller capitals in the region such as Caracas and, most recently, Quito, have built them. But now, it looks like bogotanos’ time has come.

After decades of studies and abandoned plans, and debate over whether the system should run underground or not, a contract was finally signed in 2019. Construction began in 2021 on the city’s first line, which will run mostly above-ground.

The 14-mile line, with 16 stops, is being built by a Chinese consortium—an example of China’s increasingly active participation in the region’s infrastructure public tenders. Line 1 is projected to start operating by 2028. Mayor Claudia López announced in mid-May that the process to hire a company to build a second, mostly underground line is already underway.

Why did it take so long for Bogotá to begin building its first metro, what finally made it happen and how will it change the lives of Bogotá residents?

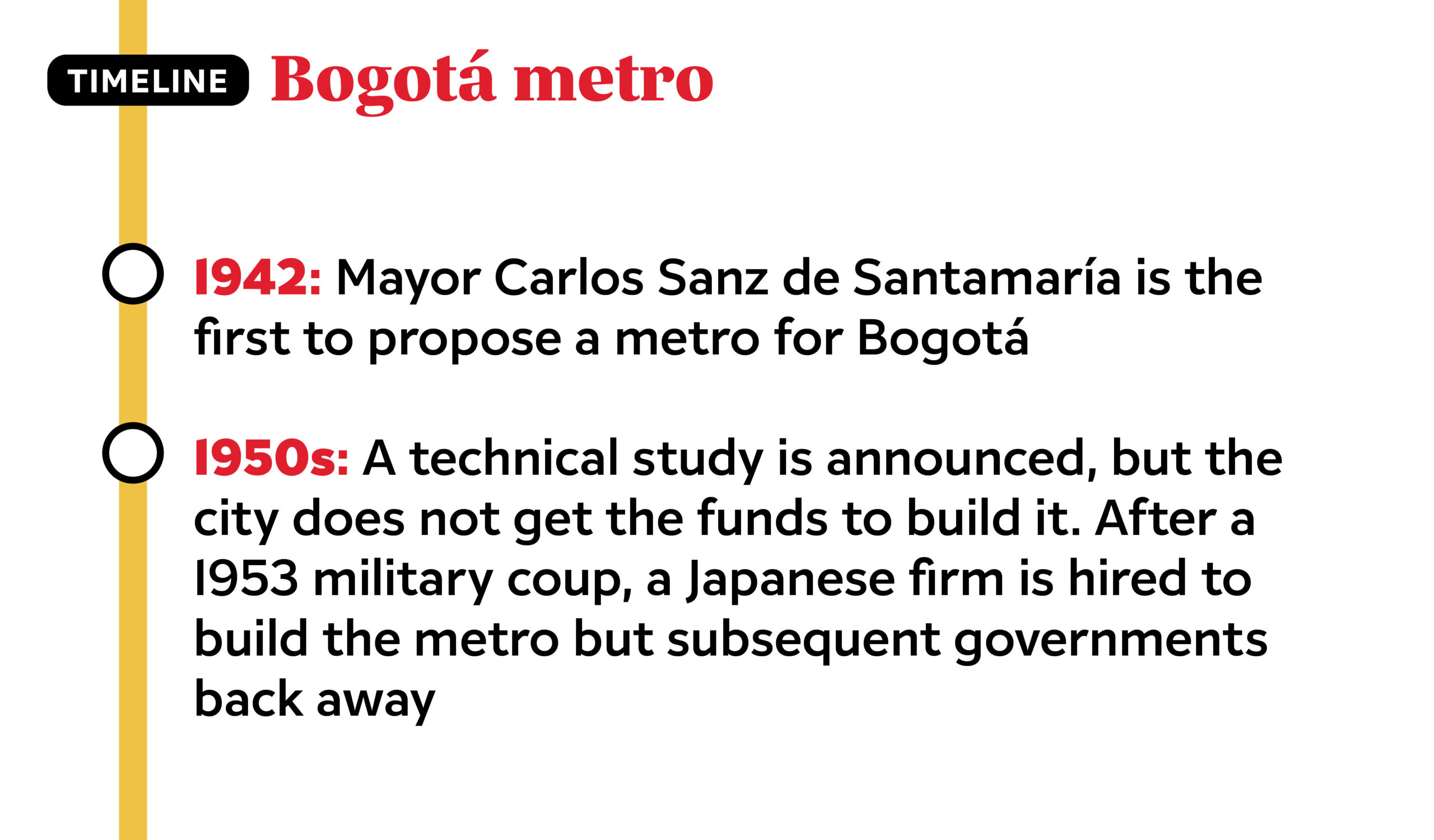

The first time a mayor of Bogotá proposed the construction of a metro was in 1942. At the time, the city had 400,000 residents, and packed trolleys carried half the city’s population every day. Many a mayor since has tried to build it.

The trouble has been political and economic, according to Andrés Escobar, an engineer and former manager of Empresa Metro Bogotá. Building a metro is expensive, and the local administration never had the money to advance the project without the support of the national government. (The cost of the first line will be over $4 billion. Seventy percent comes from national coffers and the rest from district funds.)

However, national and local interests never quite aligned, with different political groups controlling the city and the presidency for much of recent history. “Whenever a metro project has been interrupted, it’s been because there was a change in administration, either at the local or national level,” said Darío Hidalgo, a professor of transport and logistical studies at Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá.

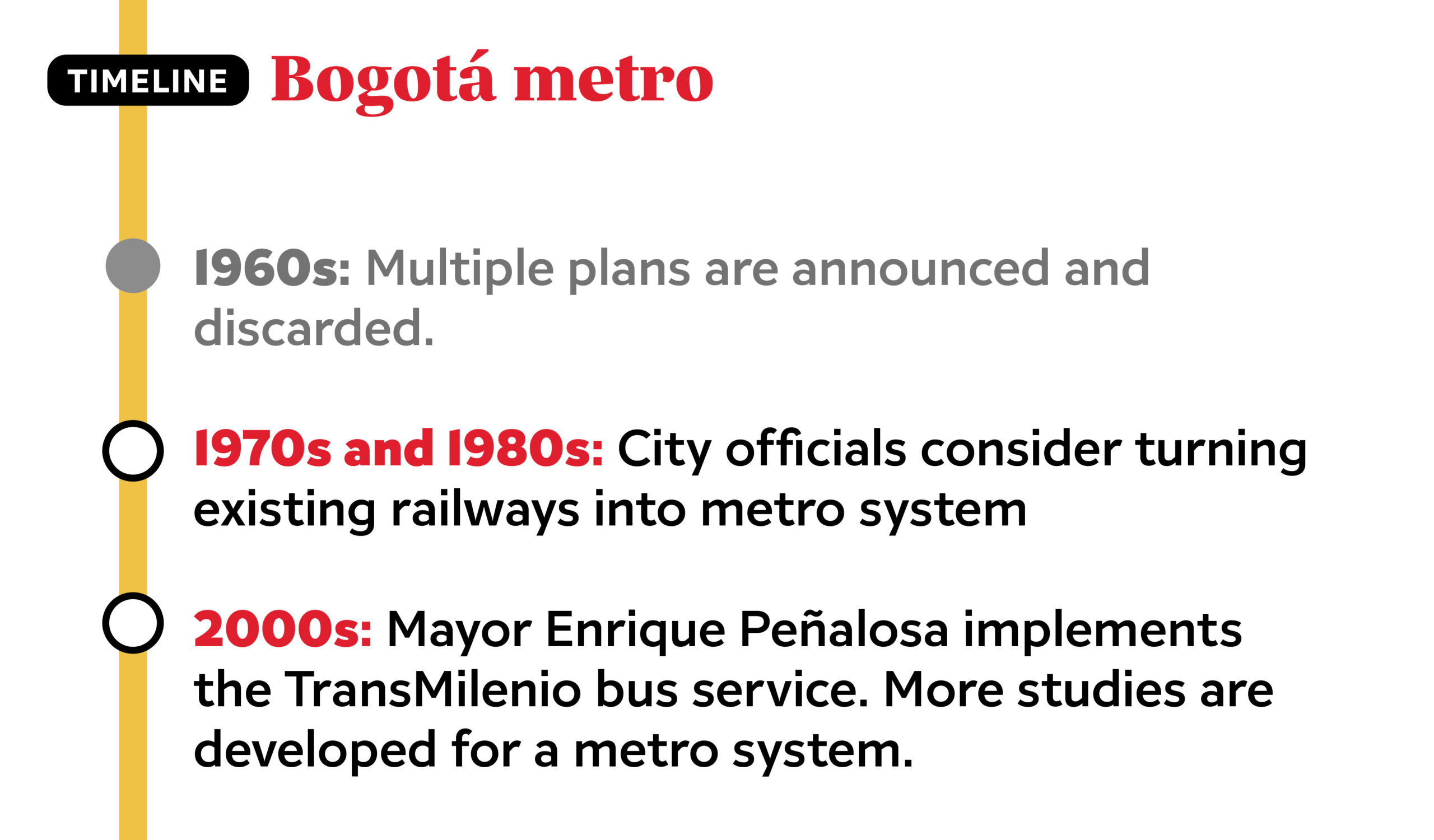

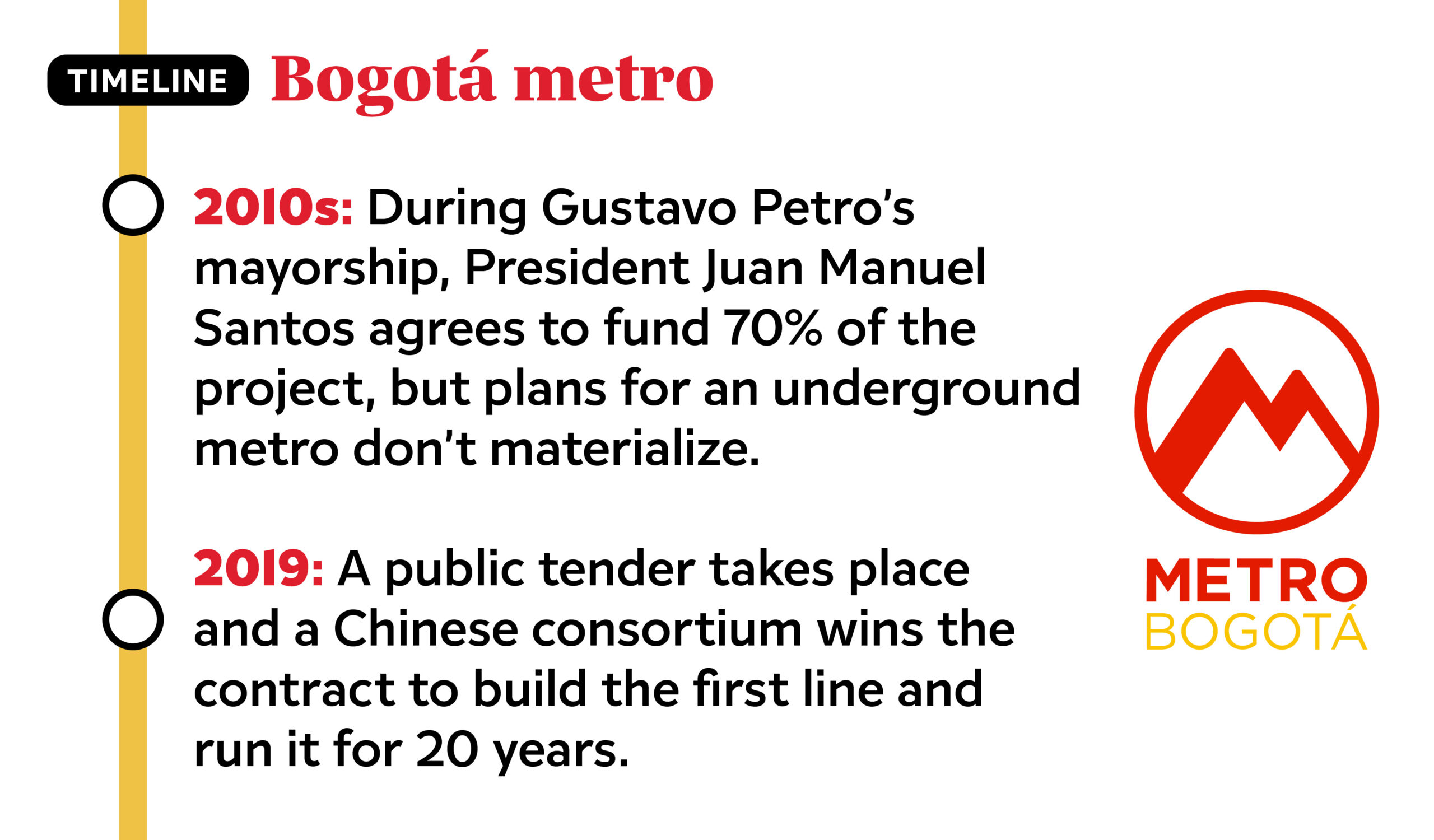

When current President Gustavo Petro was mayor from 2012-16, plans advanced significantly for an underground line. Then-President Juan Manuel Santos agreed to fund 70% of the project. But Petro’s administration ended before studies could be completed and a public tender could be held. Then came Mayor Enrique Peñalosa, Petro’s political rival, who pushed for an overground line. Although the current mayor, Claudia López, had initially said she was in favor of an underground version, she decided to move the project along as it was. “The best line there is the one that is built; the worst is the one that is only on paper,” she said.

Petro always made the case for an underground metro, arguing that an overground train will damage neighborhoods in its way. Although few disagree that an underground subway would be the best option, it’s also much more expensive. The debate prolonged the process and added to costs; in the past decade, the city spent 118 million pesos (around $26 million) on technical studies.

Enter the Chinese consortium, which won the public tender, according to Escobar, because it offered the lowest price for construction of the first line. In the process, it outbid Mexico’s Carso Infraestructura y Construcción and Promotora del Desarrollo de America Latina, Spain’s FCC Concesiones de Infraestructura and Ferrocarril Metropolità de Barcelona and France’s Alstom SA.

The contract was signed under President Iván Duque (2018-22), who steadily strengthened Colombia’s relationship with China. To many observers, the metro contract was the investment that signaled China’s real arrival in Colombia. In 2019, contracts with Chinese firms were also signed to provide Medellín’s first electric bus fleet, build a highway in the south of the country and a train that will link the center of Bogotá to its metro area.

As president, Petro has tried to modify the project once again to put Line 1 partly underground. The move pits the presidency against the district, and the discussion could end up in court, according to La Silla Vacía’s Bogotá reporter Paula Doria. Despite Petro’s continued attempts to alter the project, construction is moving forward, and most observers agree the presidency does not have the power to stop it.

What changes for bogotanos?

Today, 43% of commuters use Transmilenio, the express bus corridor system that transports over 2 million people every day. Meanwhile, Bogotá is the Latin American city that accounts for the highest number of bicycle trips per day.

Still, the Colombian capital has the worst traffic in the Americas, and the fourth-worst in the world, after Istanbul, Moscow and Kiev, according to an index by Tomtom. And bogotanos often express dissatisfaction with the Transmilenio service, especially women.

Though mobility experts mostly praise the arrival of a metro, they warn that this alone will not solve the city’s transport problems. The first line will account for only 6%-7% of daily trips in the city. Experts say other public means of transport must be strengthened, and they should be integrated with alternatives like bicycles.

“Bogotanos have to be a little patient during this stage. After many years of not doing the big works that were required for better mobility, Bogotá will now have this great opportunity. We are going to have three or four years in which the situation is still not very good, but then hopefully we are going to have much better mobility”, said Hidalgo, the professor.