Gustavo Petro’s recent victory in Colombia has cast new urgency on an old question: What is the future of mining and oil exploration in Latin America? Especially in the countries of the Andes, where leaders and social movements in several countries have also been critical of “extractivism”?

Indeed, the debate seems to be raging everywhere. As many as 65 community-level mining conflicts are simmering in Peru. In Chile, the world’s top copper producer, the Constitutional Convention is proposing environmental language that could in practice scale back mining. In Bolivia, debates within the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) party are calling into question a long consensus over natural resources. In Ecuador, massive protests against the government included demands for a moratorium on new mining activity.

The situations vary, but observers consulted by AQ highlighted two dynamics at play.

On the one hand, some Andean leaders have in recent years put aside environmental concerns once reaching office in order to focus on pragmatic goals like poverty reduction. On the other, the ability of leftist leaders in places like Bolivia and Ecuador to forge a so-called “extractive consensus” among their supporters around mining seems to be fraying as concerns over climate change and other consequences continue to increase.

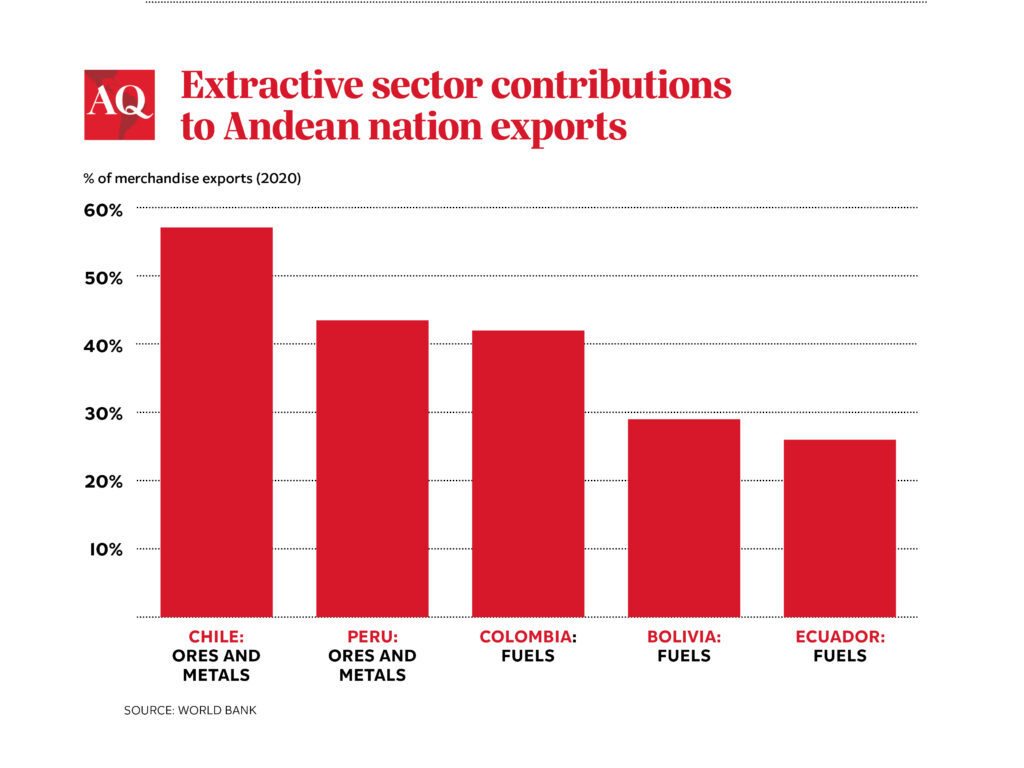

Consider the case of Petro, who as a candidate consistently vowed to halt new oil exploration and oppose fracking, saying he wants to create a Colombian economy that is greener and focuses less on export of a single commodity. In fact, petroleum currently accounts for a large chunk of Colombia’s economy: 36% of exports by value, 17% of government revenue and 2.7% of GDP in the first quarter of this year.

That’s why some observers believe Petro will eventually moderate his stance, especially as he faces inflation and a fiscal crisis precipitated by pandemic subsidies—on top of rising interest rates and perhaps a global recession, two prospects that were barely mentioned during the presidential race. “After the dust settles, (Petro) will become more pragmatic,” Mauricio Cardenas, a former finance and energy minister in Juan Manuel Santos’ government, told AQ.

There is a model that suggests Petro could adopt a more accommodating stance without losing popular support. Former presidents Evo Morales of Bolivia and Rafael Correa of Ecuador, also of the left, were both able to consolidate a robust “extractive consensus” by showing that revenues would be invested equitably in affected communities and in society as a whole, said Bret Gustafson, an anthropology professor and author of Bolivia in the Age of Gas (2021).

Bolivia and Ecuador

Indeed, in Bolivia, the MAS with Morales at the helm from 2005 to 2019 depended highly on mineral revenues and was generally popular, even in communities affected by mining projects. More than 1.2 million people, or roughly 10% of Bolivia’s population, joined the middle class under his government.

Now, however, the MAS’ political dominance is faltering as internal divisions become more pronounced. “The fact that you have ex-MASistas who are not necessarily in the fold anymore means that you’re going to get a more varied set of conversations,” said Robert Albro, a professor of anthropology specialized in Bolivian political organizing.

The so-called TIPNIS highway proposal, which was championed by Morales, is emblematic of this debate, Albro said. The highway was meant to facilitate gas exports to the Brazilian market, but was ultimately shelved due to intense resistance from some Indigenous communities—though others supported it.

This reflected increasing tension over how to balance national interests with local interests in redistribution and harm reduction, and the debate is still shifting. Now, right-leaning local government councils called civic committees are leading protests against lithium mines, adopting the tactics of traditionally leftist anti-extractive movements. They are demanding a greater cut of revenue for local populations, but also seek to dent the MAS’ popularity, Albro told AQ.

The civic committee of Potosí, a major mining hub, is a case in point. “Their goal is to disrupt the industrialization at scale of the lithium industry in Bolivia,” Albro said. Still, they remain on the fringes of the political landscape without a large grassroots base, and the extractive consensus is largely intact, so the MAS is likely to be able to outmaneuver them by making popular redistributive adjustments.

Meanwhile, Ecuador’s extractive consensus, which even under Correa showed signs of fragility, has continued to fray under conservative President Guillermo Lasso. Major demonstrations led primarily by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) have been ongoing since June 13, focused on fuel prices, cost of living, unemployment and public spending on health care and education.

CONAIE also included in its 10-point list of demands a moratorium on new oil and mining projects. It emphasizes the need for better harm mitigation policies as well as guarantees that projects will move forward only when affected Indigenous communities have given input on and agreed to their terms.

Grassroots receptiveness to oil and mining projects hinges on confidence that the environmental damage they cause will be repaired and that revenues will bring tangible benefits to impacted regions. The protests show that when this confidence fades, these issues are swept up into larger social and economic debates.

Peru and Chile

In Peru, the longstanding lack of effective revenue distribution has led to today’s slew of mining conflicts, Tania Paronia Tarqui, a Quechua community leader and former member of Peru’s Congress, told AQ.

The government of President Pedro Castillo has not earned the credibility that the MAS developed in Bolivia and Correa developed in Ecuador, Paronia Tarqui explained. The government has too often inked agreements with multinational companies that are “permissive and weak and full of loopholes” in terms of social and environmental commitments, she said.

All this reinforces community-level concerns over corruption. The IMF estimates that the state takes a sizeable average of 42% on profits. Much of that take is managed by local governments, but those that receive the most mining revenue often have especially low rates of budget execution.

In 2021, Peru’s mining industry accounted for 14% of government revenue, and mining conflicts have become increasingly costly. The National Mining, Oil and Energy Society (SNMPE) estimated that conflicts around nine mines have cost the industry $1.16 billion and the Peruvian government $348 million in revenue.

President Pedro Castillo campaigned on reforming revenue distribution and was immensely popular in mining regions. His administration, however, has offered inconsistent rhetoric on mine protests and has failed to craft popular reforms amid repeated cabinet reshuffles.

In Chile, critics of the Constitutional Convention—which is preparing a draft constitution for a vote on September 4—fear that proposed environmental language will lead to a context more like Peru’s than Bolivia’s. The Convention is poised to give ecosystems rights along the lines of the constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia, but such a constitution may put a stronger brake on growth in Chile, the world’s largest copper producer, Patricio Navia, a Chilean political scientist at New York University, told AQ.

Navia explained that mining is more likely to be inhibited by such a constitution than oil or gas development—which Ecuador and Bolivia have focused on, respectively—due to its more overt environmental harms. He also emphasized that mining is the heart of Chile’s economy, accounting for around 12.5% of GDP.

This may jeopardize the Convention’s proposals for new social spending. If the draft constitution is approved, “what will likely happen is we will have to increase the extractive industry to pay for all the social rights the (draft) is promising,” said Navia.

For its part, the administration of President Gabriel Boric has said it wants to raise taxes on mining—not eliminate it—to fund social spending. Defenders of the draft constitution also point out that the Convention voted down proposals to significantly reform the mining sector, and that though it would ban mining on glaciers, moves to ban mining in salt flats, wetlands and other fragile ecosystems failed, ensuring that Chile will continue to exploit lithium.

Bolivia and Ecuador show that credible systems of harm mitigation and revenue distribution reduce conflict over oil and mining, but also that they remain a work in progress. Time will tell whether the draft constitution in Chile, government action in Peru or political expediency in Colombia will get these countries closer to their own extractive consensus.