President Donald J. Trump has announced ambitious goals for his Latin America agenda, including plans to impose tariffs on Mexico, reshape U.S. border and immigration policies, and possibly take back the Panama Canal. But when it comes to Venezuela, recent events suggest he may be casting aside the aggressive policies—known as the “maximum pressure” strategy—adopted during his first presidency.

In a demonstration of pragmatism toward Venezuela, Richard Grenell, Trump’s envoy for “special missions,” met with Nicolás Maduro on January 31 in Caracas and struck a deal to secure the release of six Americans imprisoned by the regime. At the same time, Grenell set the terms for the repatriation of Venezuelans living in the U.S.—including members of the notorious Tren de Aragua gang—as the administration moved to revoke Venezuelan migrants’ Temporary Protected Status.

A day later, on February 1, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) automatically renewed the general license #41 allowing Chevron Corporation to operate in Venezuela. Initially issued in 2022, this license is an essential funding source for Maduro’s regime, and since 2023 it’s been placed on automatic renewal if no decision changes its course.

While this sequence of events may have been coincidental, those in politics understand that certain things happen for a reason. Even if the meeting in Caracas doesn’t imply that the Trump administration recognizes Maduro as Venezuela’s legitimate president, the early moves seem to prioritize short-term goals and indicate that hopes for a new “maximum pressure” strategy need to be tempered. Loftier aims—like helping to restore democracy in Venezuela—appear to have been put on hold, highlighting the need for a realistic policy toward the Latin American country.

Nonetheless, this practical strategy might clash with the oil licensing policies. While the initial agreements reached with Grenell demand moderation in Maduro’s authoritarian actions, the oil licenses enhance his financial power without oversight or accountability. As Maduro embarks on a spurious third term following a disputed election and inauguration on January 10, the Trump administration may face a pivotal decision concerning Venezuela and the regional implications of its ongoing crisis.

A possible way forward

U.S. policy toward Venezuela seems to boil down to two possible paths. One option is to maintain the oil licenses, which some argue could improve Venezuela’s economic conditions and deter new, massive migration that would add to the already unprecedented diaspora in the Western Hemisphere.

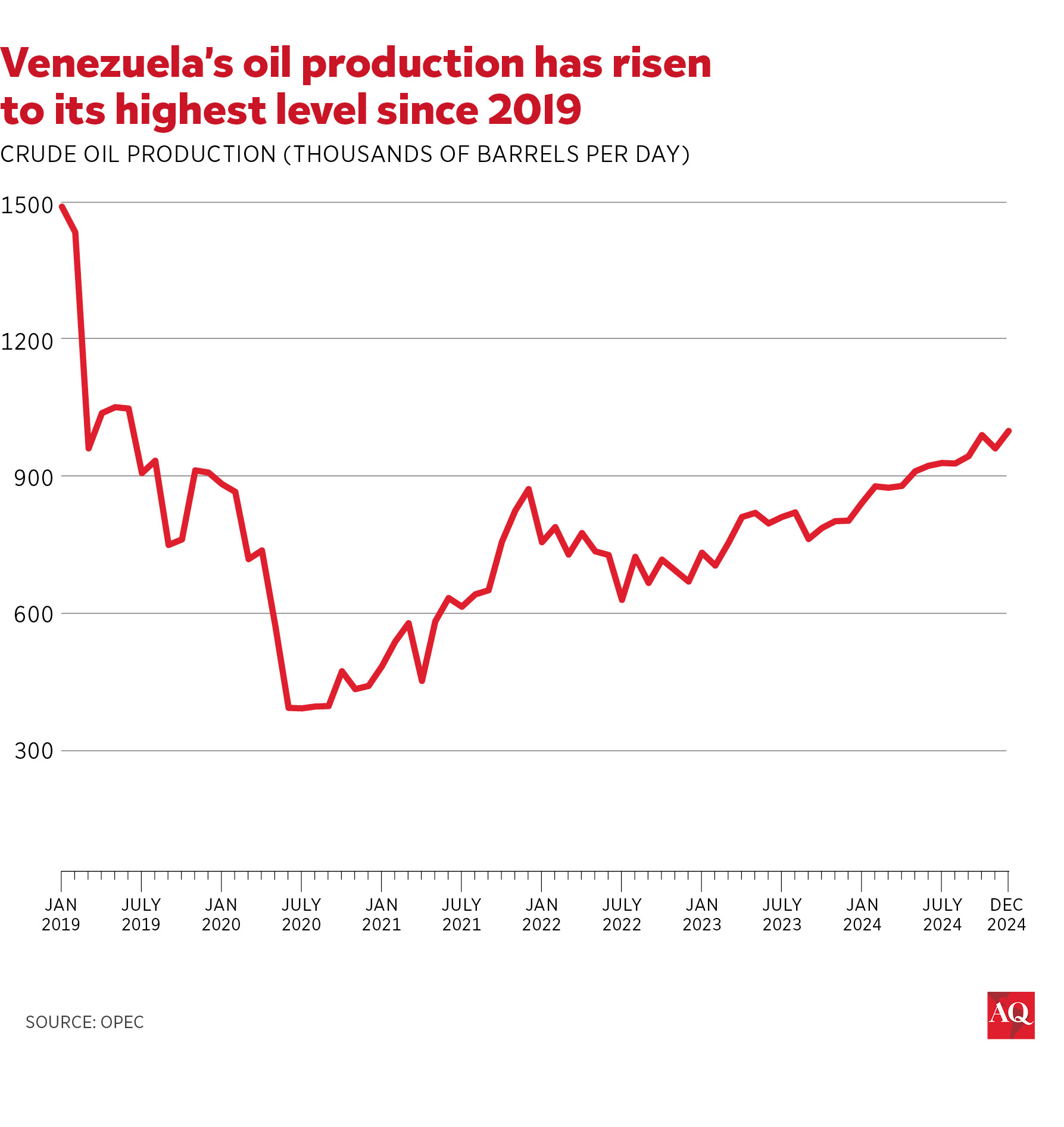

The other option involves revising the oil policy and moving toward a stricter posture against Maduro and his cronies. The White House could choose to cancel the Chevron license or let it expire at any time. Democrats and Republicans in Congress called on the Biden administration to do so, but Biden kept it afloat. According to some estimates, Chevron’s licensed operations account for around 25% of Venezuela’s production, which closed 2024 at around 886,000 barrels per day.

For its part, the Trump administration hasn’t necessarily jettisoned options to pressure Maduro. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s comments during his confirmation hearing hinted at the possibility of “reexploring” Chevron’s license. His statements demonstrated that the new administration is aware of the negative consequences of oil licenses: empowering Maduro with billions of petrodollars that he can administer however he wants is not the best way to encourage the restoration of democracy.

Moreover, in one of Trump’s few remarks on Venezuela, he declared that the U.S. would likely stop buying Venezuelan oil. This does not indicate that the oil licenses will be revoked, but rather that Venezuelan oil is unimportant to the U.S., particularly after he signed an executive order to boost domestic production.

Maduro’s enhanced financial capacity

Under the current sanctions framework, Maduro’s financial position has improved significantly, as he receives a share of the production covered by the licenses. He can capture and distribute these at will because new oil businesses are regulated by the Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Law, an unconstitutional 2020 law that grants Maduro absolute power to make any deal in strict secrecy. Because of this lack of transparency, there is no public information about how much money Maduro receives.

However, we can estimate that the licensed companies produce roughly a third of Venezuela’s oil output. The government takes at least a third of that licensed production in royalties and taxes, though the figure could be as high as 50%. Considering December 2024 production—886,000 barrels per day, per OPEC’s secondary sources—and a Merey crude price of $61.13, we can estimate that Maduro receives between $2.1 and $3.2 billion annually. The actual number could be higher or lower, but either way, licensed companies provide billions of dollars that Maduro administers without transparency or accountability.

While some experts claim that licenses have promoted transparency in the oil industry, the evidence suggests the opposite. Due to the Anti-Blockade Law, new oil revenues support kleptocrats and human rights violations rather than the Venezuelan people.

Paradoxically, part of the sanctions regime gives Maduro even greater freedom to use the funds however he wants. Certain sanctions largely forbid governments and other bond-holders from negotiating with Maduro to recover any part of the country’s $200 billion debt in the wake of its default in 2017. Maduro has even avoided the pressures from the Delaware District Court, which handles the complex sale process of Citgo Petroleum’s parent company, PDV Holding Inc.

Tackling contradictions

Venezuela ranks as the 13th most corrupt country globally and dead last in terms of rule of law. Given institutional conditions indicative of kleptocracy, oil revenues will likely serve only to foster corruption and aid criminal organizations like Tren de Aragua.

Measures could be taken to restrict Maduro from freely using oil revenues as a first step to solving these issues. Revoking the licenses isn’t the sole way to address this imbalance (this could have undesired effects). Other policy options include reforming the licenses to create transparency duties, creating a humanitarian fund to be financed with petrodollars, or shifting part of the economic burden of the debt to Maduro.

Without these measures, oil revenues will incentivize autocratic policies, undermining the Maduro regime’s ability to fulfill the commitments made with the Trump administration. In the medium term, to effectively address the security concerns raised by the U.S. government—particularly those related to criminal organizations—it is crucial to establish political institutions that foster development, law, and order—something currently impossible. However, at the very least, restricting Maduro’s financial resources would help achieve the initial policy objectives of the Trump administration.

One critical lesson from the recently Nobel Prize-awarded work of Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson is that stable economic growth, peace, and order are impossible to foster without the rule of law and a capable state. Particularly after his self-proclamation, Maduro has demonstrated that he has no interest in democratization and that he can maintain his autocratic grip only through criminality, corruption, and human rights violations, the root causes of the mass migration crisis.

The U.S. has a key role to play. The new Trump administration has the opportunity to act beyond short-term deals and help Venezuela, preventing the country from entering its darkest era, which would endanger security in the Western Hemisphere.