GUATEMALA CITY — As the leader of Guatemala’s most influential Indigenous district, Luis Haroldo Pacheco helped to lead the longest protest in the country’s recent history. Over 105 days, protesters blocked traffic at 142 points across the country to ensure that Bernardo Arévalo would be sworn in as president after winning last year’s elections.

It’s unlikely that Arévalo would have taken office without this support. Now, 100 days after Arévalo’s inauguration, Pacheco is disappointed. “It is sad to see how part of the new administration is coddling those who tried to overturn the election,” he told AQ. “Our demand … was that they resign or get kicked out.”

Arévalo, a center-left reformer who campaigned on combating Guatemala’s endemic corruption, has faced fierce resistance to his efforts to improve transparency and pass legislation. He has made some progress on efforts to clean up public works contracting, push meritocracy in the Cabinet, and restore Guatemala’s image on the world stage. He counsels patience: “There are institutions that are still co-opted by these criminal political elites who tried to overturn the election, and we are definitively in an effort to recover control,” Arévalo said in a televised interview on April 15.

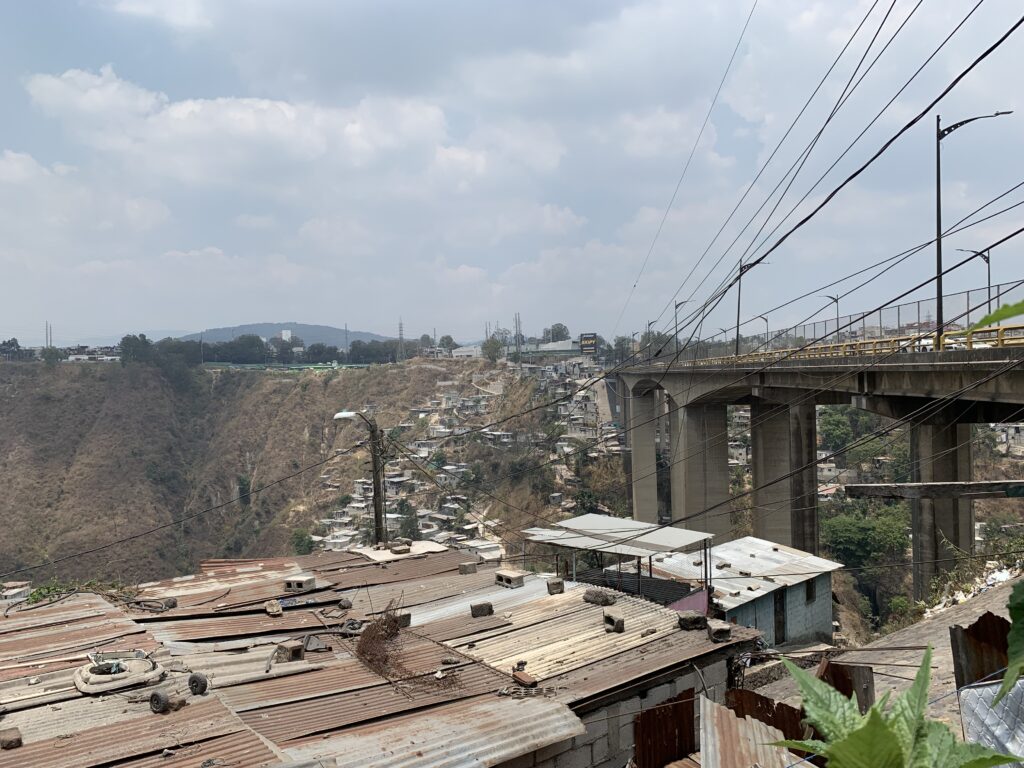

But many of his most ardent supporters are wary of how slow progress has been and worry that a window for meaningful change is closing. “I had too much hope,” said Erwin Rivera, a community leader in El Incienso, one of Guatemala City’s toughest neighborhoods, who played a leading role in the 2023 protests. “They don’t have the courage to impose themselves or they don’t know how to do it,” he told AQ.

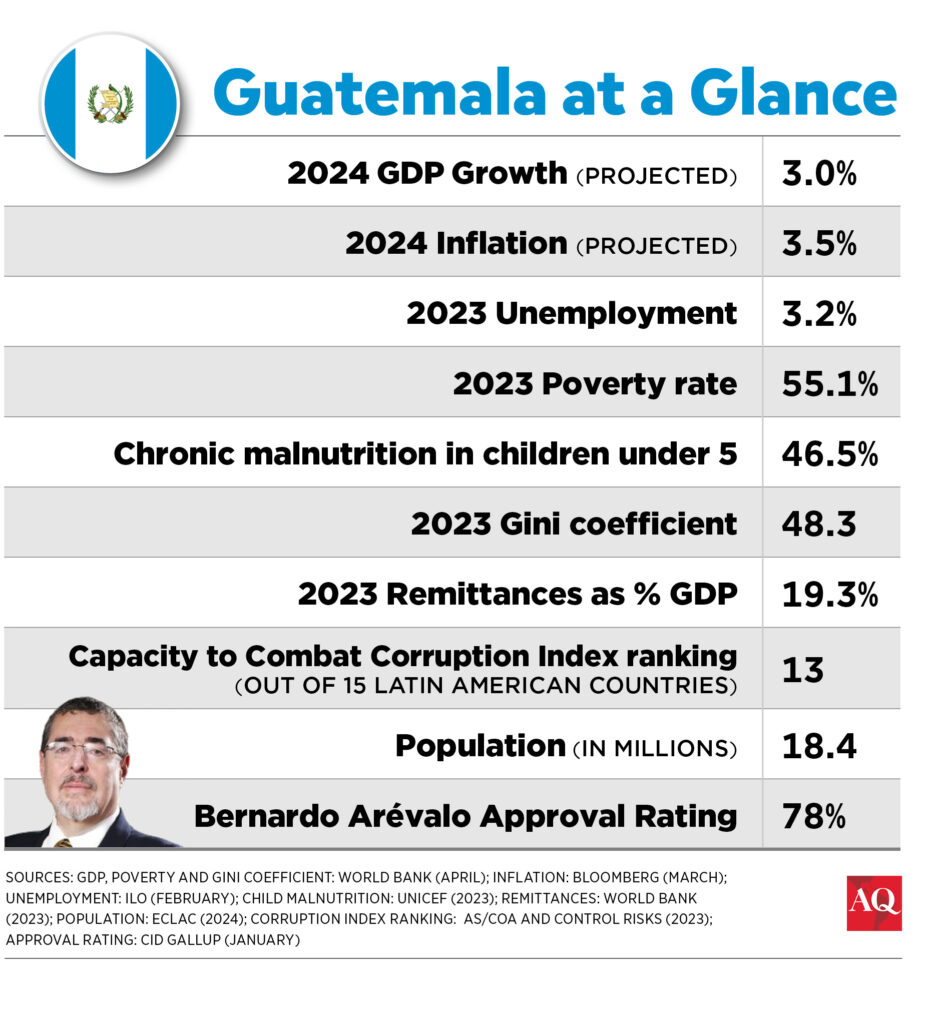

So far, Arévalo remains overwhelmingly popular; the latest CID Gallup poll shows a 78% approval rating, Latin America’s third-highest. The World Bank expects Guatemala’s economy to continue to outpace the regional average, growing 3% this year. The capital’s atmosphere has improved as a tide of prosecutions of anti-corruption journalists, judges, and prosecutors has ebbed.

But Arévalo’s principal antagonist, Attorney General Consuelo Porras—sanctioned by the U.S. and EU for allegedly undermining democracy through politically motivated investigations—remains in office. (She denies wrongdoing.) Arévalo cannot remove her before the end of her term in 2026, and his efforts to pressure her to resign have come to naught. Meanwhile, Arévalo, Vice President Karin Herrera, and other members of their Semilla party remain under investigation and are threatened with the prospect of prosecution—along with Elections Court judges who refused to decertify Arévalo’s victory.

Other fronts

Moreover, the sensation of greater freedom is periodically undermined. Prosecutor Miriam Reguero, known for her hard-hitting corruption investigations, was arrested on April 11, seemingly the latest official to be pursued for taking on graft. Her arrest came just two weeks after she was targeted in an assassination attempt in which her mother and her bodyguard were killed.

As Porras continues to stonewall anti-corruption investigations, the Constitutional Court and obstructionist members of Congress have tied Arévalo’s hands and chipped away at Semilla’s powers in the legislature. And on April 14, Constitutional Court judge Néster Vásquez, sanctioned by the U.S. for alleged links to corruption, became the CC’s president. (He denies wrongdoing.) This has observers concerned that corruption networks will outmaneuver Arévalo during the next major test of the justice system: new nominations to the Supreme Court of Justice and high appeals courts in October.

The administration has tried to tackle graft through the National Anti-Corruption Commission, now headed by Arévalo appointee Santiago Palomo, a career court official and Harvard law graduate with a solid track record. Palomo has vowed to “strengthen integrity and transparency” in government contracting, address the challenges posed by money laundering, and identify the biggest beneficiaries of organized crime and corruption networks. This could dramatically improve the efficiency of public spending and prospects for foreign direct investment. But without the assets of the Public Ministry at his disposal, it’s unclear how much progress he can make.

International gains

Thus far, reinserting Guatemala in the international arena has represented Arévalo’s chief accomplishment. In February, he visited Germany, France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Spain, in an effort to reopen collaboration on new investments, while a month later, he paid his first official visit to the U.S., reviewing issues such as migration and transparency. Upon his return, he highlighted the achievements of that first tour: new promises of foreign investment and aid, and new proposals on migration and security. Even so, it remains to be seen whether these promises and proposals bear any tangible fruit. There are signs pointing in the right direction, including encouraging visits from potential investors, ranging from Spanish businessmen to representatives of Mexican conglomerate Grupo Salinas, Haroldo Sánchez, a government spokesman, told AQ.

Still, on balance, the small victories in Arévalo’s first 100 days count for little, said political analyst and professor Marielos Chang. It is crucial to remember that his election put a brake on a rapid authoritarian regression that seemed unstoppable before last year’s election, she said, but Arévalo has not shown that he understands the urgency of the moment. “If Semilla doesn’t do a good job, after four years [Arévalo] won’t hand over power to just another candidate, he’ll hand it over to the mafias,” she told AQ.

In Totonicapán, a department in Guatemala’s northwestern highlands, Pacheco hasn’t lost hope. “I’m confident they can get back on track by listening to Indigenous authorities, valuing new voices and purging those who should be purged,” he told AQ.

From the slopes of Guatemala City’s Incienso neighborhood, where narrow houses with tin roofs are huddled in a deep ravine, Rivera agreed, but with a caveat. He is certain the problems that afflict urban neighborhoods like his, and those of the country’s impoverished rural regions, are at root political.

To solve them, the public needs to continue to organize. “We can’t wait for the government and politicians to solve our problems,” Rivera said. “It is we, the people, who must take the lead, because we have shown that we can do it.”

Chang, for her part, is looking for political clarity from the administration. “It’s been 100 days, and we don’t know what moves Bernardo Arévalo, what his great cause is, what he wants his legacy to be,” she said.

Guatemala’s democracy continues to hang in the balance. To much of the public, the Arévalo administration seems mired in uncertainty—along with the country’s future.