This piece was updated on July 26

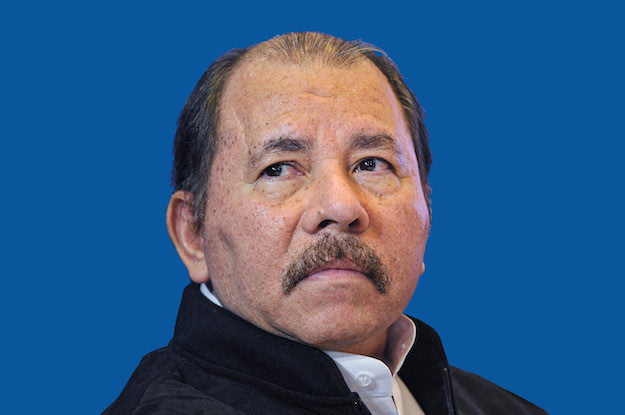

Daniel Ortega

75, president

Sandinista Liberation Front

“Whoever does not defend Nicaragua and asks for sanctions against Nicaragua, he does not deserve to call himself Nicaraguan. He has already lost his rights to run for public office.”

WHY IT’S NOT DEMOCRATIC

As of October 25, President Daniel Ortega’s government had detained over three dozen opposition figures, including seven presidential hopefuls and the president and vice president of the largest business federation, the Superior Council for Private Enterprise (COSEP). Nearly all who have been arrested are being held under a treason law that was passed in December by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN)-controlled National Assembly and gives Ortega’s government the power to label citizens “terrorists” and ban them from running for office. Even before the arrests, Ortega had created a legal framework to consolidate power and ensure victory. On May 18, the Supreme Electoral Council, the body that oversees elections, took away the Democratic Restoration Party’s (PRD) legal status, eliminating a major opposition bloc from the ballot. In October 2020, the Foreign Agents Law and the Special Cybercrimes Law were passed to legally restrict freedom of expression and association, and the National Police was granted the power to prohibit political gatherings. Ortega has also rejected international electoral observation against the recommendation of the Organization of American States. Secretary General Luis Almagro of the OAS said that Nicaragua was on track to have “the worst possible election.”

WHAT THE OPPOSITION LOOKS LIKE

The opposition remains generally divided in two main groups, the National Coalition and the Citizen Alliance. After intense negotiations leading up to the May 12 deadline to register political alliances – set by the newly approved Supreme Electoral Council – the opposition failed to unite. One political party, the Citizens for Freedom, representing the Citizens Alliance, registered with the Supreme Electoral Council, ending hopes of a coalition around one opposition candidate challenging Ortega at the ballot box. With the PRD officially out of the running, the National Coalition would need to support the Citizen Alliance, experts told AQ, since putting up a united front is the opposition’s only chance to fight Ortega. Yet, over 60% of Nicaraguans do not even identify with any political party, according to recent polls.

HOW HE GOT HERE

Ortega first rose to power in the wake of the Sandinista party’s overthrow of the U.S.-backed Somoza dictatorship in 1979. Part of the Sandinista governing junta, he would go on to win the presidency in open elections in 1984, later losing a re-election bid to Violeta Chamorro of the National Opposition Union in 1990. He was reelected in 2006, and became a popular leader, relying on Venezuelan oil to fund welfare programs. In 2014 he passed a set of constitutional amendments, approved by the FSLN-dominated National Assembly, to abolish term limits. This allowed him to be reelected in 2016. Flanked by Vice President and First Lady Rosario Murillo, the president has tightened his grip ever since.

WHAT HE MIGHT DO

Ortega is likely to continue the regime’s repressive tactics of muzzling the opposition and the media, showing no signs of stopping after an electoral victory. His handling of the economy – GDP has been shrinking since 2017 – and the COVID-19 health crisis have helped erode his popularity ratings. An Inter-American Dialogue poll conducted in July has shown his approval falling below 20%, his lowest ever. International support may continue to falter, as the country’s close ally and financial supporter, Venezuela, is itself under sanctions. In mid-September, the Club de Madrid, an influential group of former presidents and prime ministers, called for international lenders to freeze the Nicaraguan government’s supply of finances. Still, there are no signs that Ortega will yield to international pressure during a possible third term. He recently rejected a report by the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights warning of the growing human rights crisis, and he reiterated demands for an end to sanctions from the U.S. Without a change in tactics, experts say it is likely the destabilizing forces of the economic and health crisis will deepen and social unrest will continue to mount.