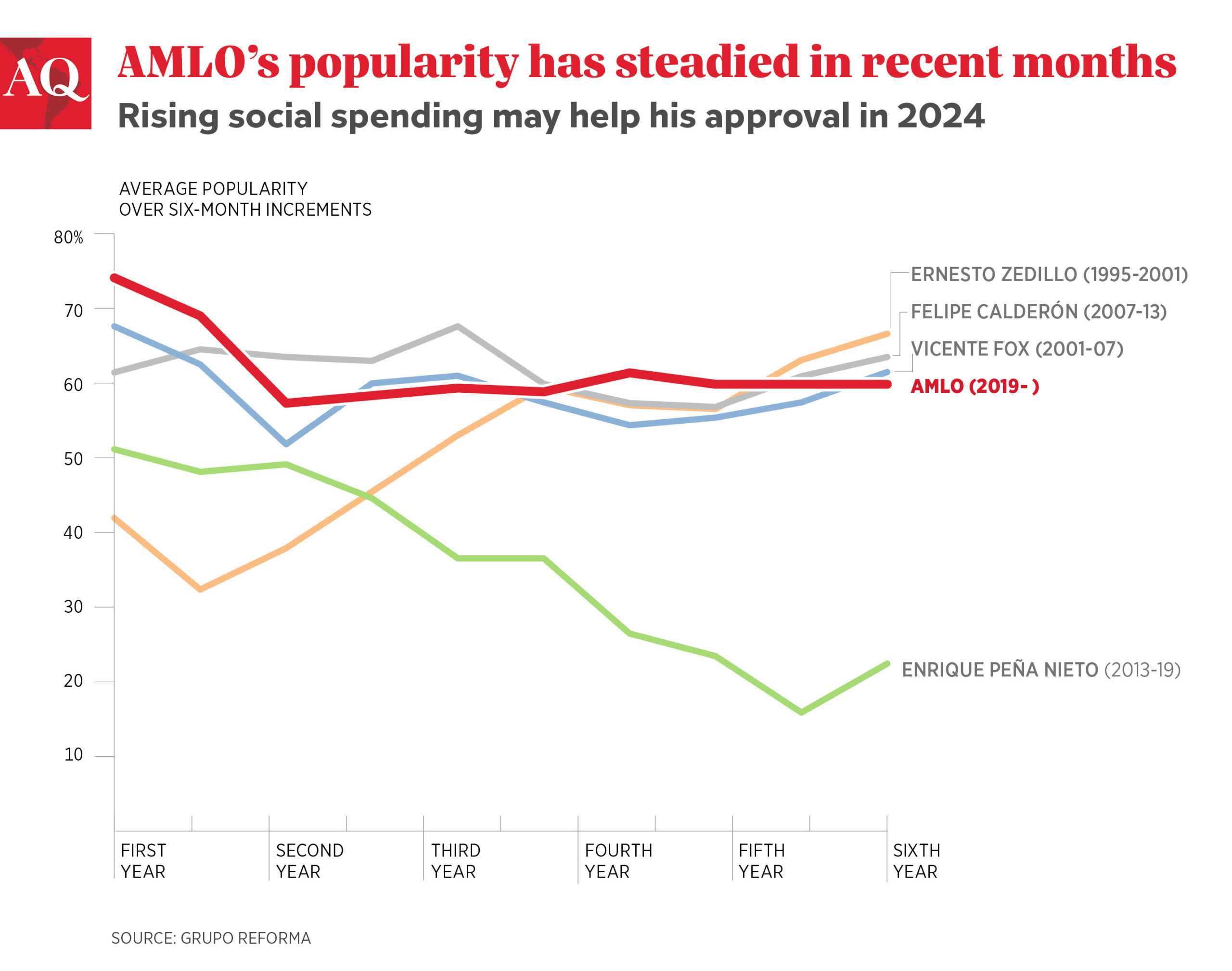

If you thought Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s popularity was on the verge of decline, it’s worth revisiting your expectations. With the president already in his last year in power, it would be reasonable to expect a deterioration of his approval rating, especially considering his contentious relationship with different sectors of corporate Mexico, a poor track record on the economy—with 0.9% annual growth on average, despite still robust public finances—and the dubious effectiveness of the fight against organized crime. But AMLO’s tenure may find new life in the months ahead.

Early in his presidency, AMLO’s popularity soared to over 80%, the highest any Mexican president has seen since at least the 1980s. Even more remarkably, his approval ratings have stabilized at around 60% in recent months, one of the highest in the region ( according to pollster Mitofsky), and just behind other populist global leaders, such as President Nayib Bukele, in El Salvador (93%), and India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi (75%).

Building a legacy in his final year in office, AMLO intends to resort to one tool that served him well during his first five years in power: social spending.

To cement his popularity, the president has used social programs for clientelist purposes with great effectiveness, along with an appealing (albeit polarizing) narrative and strong disenchantment with the traditional political class. Welfare and pension program spending has tripled, from $8 billion in 2018 to $24 billion in 2023. Most resources are allocated to AMLO’s social programs, primarily a basic universal pension, youth education, and training program, “The Young Building the Future” (Jovenes Construyendo el Futuro).

But spending for these programs is expected to increase next year, an election year, by an additional 25%, reaching $30 billion, according to the 2024 budget submitted by the Finance Ministry early in September for Congress’ discussion and eventual approval. While their effectiveness is questionable—the programs reach a lower number of poor households compared to previous administrations, and only 50% are deemed to have an adequate design according to independent evaluator Coneval—these social programs have proven to be a political and public perception success.

AMLO’s method

Populists such as AMLO have been good and even exceptional at creating appealing anti-systemic and anti-elite narratives (particularly for the underserved and the underrepresented), at polarizing and underlying the weaknesses and shortcomings of the liberal democratic state, but they have lacked serious delivery capacity. Institutional deterioration has been a shared legacy of populist regimes ranging from Hungary to India, Turkey, the U.S., Brazil and Mexico.

On a related note, a less tangible but relevant factor contributing to AMLO’s high approval ratings is the strong appeal of his narrative. Lopez Obrador’s rhetoric, repeated daily on his mañanera addresses, has catered to a large segment of the population that has felt persistently overlooked and unseen by the policies and politicians of the past and, most importantly, by the “culture of privilege” that is the cornerstone of access, opportunity and social advancement in the country.

The traditional political class is challenged everywhere, and Mexico is no exception. The environment of polarization and the populist regime that prevails in the country have only exacerbated the attacks on the status quo and have generated political pendulum swings with damaging reputational effects for the country, from the costly cancellation of the construction of a state-of-the-art airport, 70% complete, to the annulment of a 2013 energy reform.

The Ministry of Finance and Banxico have a track record of professionalism and technical rigor. For decades, their legal mandates have allowed both institutions to conduct sound economic policy, technically in the former case and autonomously in the latter, and to have strong incentives to ensure macroeconomic stability. For instance, despite the social programs’ spending spree, the Ministry of Finance has maintained fiscal stability based on a still sustainable debt-to-GDP ratio below 50%. On the other hand, Banxico has remained firm in its mandate to keep inflation controlled. Only last May, as signs that inflation was easing emerged, it paused a two-year cycle of contractionary monetary policy, with interest rates increasing by 725 basis points to 11.25% since July 2021. Without the ability of these two institutions to implement independent and technical macroeconomic policies and mechanisms to ensure sound and prudent policies, Mexico’s macroeconomic stance would likely have further deteriorated.

Resilient economy

There are worrying signs, however, as the country ran out of key firewalls against fiscal shocks, the so-called budgetary stabilization funds, which accounted for close to $1 billion (MXN 17 billion) in 2012 and reached over $16 billion (MXN 280 billion) by 2018, and are now mostly depleted as they have been widely used as stabilizer of public finances during AMLO’s administration.

It is indeed surprising that, despite all of these events, the country has not fallen into a steeper declining trend and that a sense of general economic and political stability, as well as well functioning democratic backstops, prevails in the perception of Mexico compared to its emerging market and Latin American peers.

The economy has proven resilient after COVID-19, disruptions of global supply chains, inflation increases, and rate hikes. It is expected to grow 3% (when the forecast back in March was between 2.2-3%), inflation remains under control reaching 4.6% year-on-year (just above Banxico’s target range of 3% +/- 1%), and debt to GDP ratio will end next year below 50% (historic PSBRs), allowing for a positive sentiment among foreign investors on the general outlook for the country, which explains the investment increase of 17.9% in the first half of 2023 according to INEGI, the most significant growth since 1993, also driven by the nearshoring expectation effect.

Yet at the same time, on the political front, the opposition alliance candidate Xóchitl Gálvez is not only battling against her political opponent, Claudia Sheinbaum. She is doing so against a very powerful and popular president, against a judicial system that is being targeted towards her and her family, and against a government that—in contrast to 2018, during the previous presidential campaign, where the deficit was deliberately and responsibly kept low at 2.1%—will run the highest fiscal deficit in 36 years, at 5.4%.