This article marks the launch of the fifth edition of the Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC) Index produced by the Americas Society/Council of the Americas and Control Risks. Click here to read the 2023 CCC Index report.

It was a year of setbacks for anti-corruption efforts, and almost no one was immune.

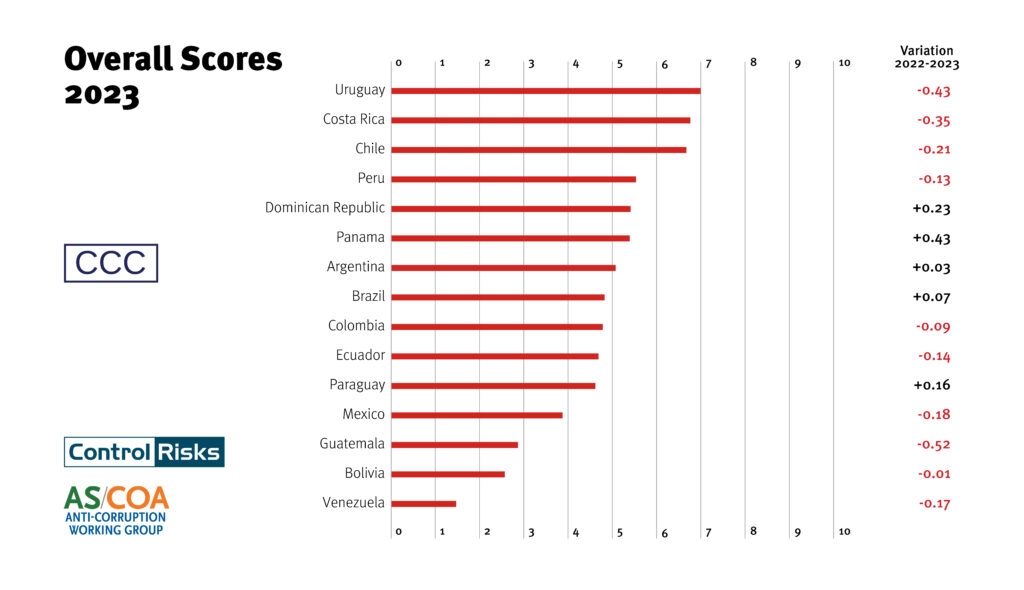

That’s the clear conclusion of the fifth annual edition of the Capacity to Combat Corruption (CCC) Index, published on June 27. Rather than measuring perceived levels of corruption as other studies do, the CCC Index evaluates and ranks 15 Latin American countries based on their ability to detect, punish and prevent corruption. In this year’s iteration, jointly published by Control Risks and the Americas Society/Council of the Americas (which publishes AQ), scores fell in 10 of those 15 countries, leading to a decline in the regional average score for the first time since 2020. Setbacks were seen among countries that did relatively well in the index, such as Uruguay, Chile and Costa Rica, as well as those which scored at the bottom, including Guatemala and Venezuela.

It’s important to note that these declines were generally not dramatic compared to 2022, reflecting a general erosion in the anti-corruption space rather than a sudden collapse. But the underlying reasons are still cause for concern. Democracies are under clear duress throughout much of Latin America, as they are throughout much of the Western world. Independent institutions, the key to effectively fighting corruption, are facing increased political pressure in several of the countries we surveyed.

Examples abound. In Guatemala, the past year saw the imprisonment of Jose Rubén Zamora, a prominent journalist who reported on corruption issues, in what many international observers saw as an attempt to silence voices critical of the government. Dozens of independent judges and prosecutors have fled that country as a result of what they see as similar persecution. In Mexico, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador clashed with the Supreme Court, tried to cut resources for the independent election regulator and regularly singled out corruption-fighting journalists and members of civil society for strong criticism.

In some countries, the story was more about how competing priorities for governments, media and civil society appeared to take attention and resources away from anti-corruption efforts. In Chile, challenges such as violent crime and immigration have become major public policy priorities, displacing other challenges. In one recent poll, Chileans ranked corruption as the 10th most pressing problem their country faces, down from the fourth position just two years prior. Uruguay once again finished at the top of this year’s CCC Index, but saw its score decline due in part to what some observers have described as insufficient funding for its main anti-corruption agency. The net result is an anti-corruption environment that is less active and mobilized than in years past.

It would be incorrect to say that corruption has entirely disappeared from the public radar in Latin America. In our index, nearly 70% of anti-corruption experts we surveyed agreed that corruption remains a “top concern for most people” in their country. Peru’s score in the index remained resilient as authorities continued to undertake major corruption investigations despite political turmoil, including the impeachment of former President Pedro Castillo. A similar story unfolded in Ecuador despite political uncertainty there. Some polls suggest that corruption is the top concern of Mexican voters heading into 2024 presidential elections. Brazil’s overall score recovered marginally, breaking three years of declines during the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, who was perceived to undermine judicial independence. It remains unclear how the new government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva will fare on anti-corruption issues.

The CCC Index draws on publicly available data as well as a proprietary survey that asks in-region experts to assess a variety of factors, including the independence of courts, the strength of democratic institutions and the freedom of investigative journalists. Its goal is not to shame or single out countries, but to foster a policy-driven discussion, helping governments, civil society and the private sector identify — through data and a robust methodology — areas of success and deficiencies to be addressed.

In that spirit, there is no real secret to fighting corruption. We know that an independent judiciary and other healthy democratic institutions are the keys to combating graft in the long term. It’s the implementation, of course, that often proves challenging. But in this era of declining faith in democracies, not just in Latin America but elsewhere, the challenge of improving governance in both the public and private spheres remains as important as ever.

—

Aalbers is a partner at Control Risks.

Winter is is the vice president for policy at AS/COA and the editor-in-chief of AQ.

Sweigart is a policy manager at AS/COA and an editor at AQ.