On the evening of December 7, Pedro Castillo probably felt something close to relief. After hours of deliberation, Peru’s Congress voted against initiating impeachment proceedings to remove him from the presidency, two weeks after a group of right-wing parliamentarians first presented the motion.

Until December 6, the situation looked bleak for the embattled Peruvian president, and not just because of the aggressive opposition he has faced from virtually all other political sectors — including from within his own party, Peru Libre — since the first day of his administration. As a series of scandals reached headlines over the past month, it seemed as though the opportunity had finally arrived for the right to get rid of Castillo, as even more centrist parties like Acción Popular and Alianza por el Progreso were publicly considering the possibility. Yet the motion to begin proceedings fell through, apparently because the opposition did not obtain the coup de grâce they were waiting for over the weekend. A highly anticipated news report, expected to present audio recordings implicating Castillo in bribery, was not released after all.

But no matter. Despite its mistakes, the opposition will get another chance, because in all likelihood Castillo will soon provide a fresh motive for his removal. Only four months into his term, multiple allegations of corruption have emerged against the president’s circle. A former Army commander has accused Castillo, his minister of defense and his chief of staff, Bruno Pacheco, of pressuring him to improperly promote officers close to Castillo. The commander claims he was forcibly retired when he refused. The head of Peru’s tax and customs agency has also accused Pacheco of pressuring him to favor certain companies who owe tax debt, which has triggered an investigation. A few days later Pacheco, who has since resigned, was found hiding $20,000 in his office bathroom. He claims the money was personal savings.

To make matters worse, on November 28, a news program presented images of Castillo meeting secretly, late at night, with a woman in a building not intended for official government business. The woman was later identified as Karelim López, a lobbyist for a company that recently won a government contract by bidding exactly 27 cents less than its competitor. It was this series of events that spurred parliamentarians from Renovación Popular, Avanza País and Fuerza Popular to present the motion of impeachment.

In an address to the country, Castillo stated that the meeting with López had been “personal” and that it was an attempt to discredit him by people who could not accept a campesino as president. In a separate announcement about efforts to collect money for orphaned children, Castillo said that he would explain the source of the funds for the project “very soon.” Regarding alleged interference in the armed forces, Castillo has only said that he respects the institution.

Scandals are overshadowing any policy advances that the government may be making. Castillo’s main proposal, changing the Constitution, seems as unlikely as ever. There is very little reporting on the legislative powers the Executive requested from Congress at the beginning of November. The vice president, Dina Boluarte, who would be first in line to succeed him, also faces significant hostility from the opposition and from within Perú Libre. Castillo’s current prime minister, Mirtha Vásquez, has been mainly dedicated to putting out the fires that seem to come out every day from the presidential palace — including her own announcement regarding the shutdown of four mines in Ayacucho, which had to be backtracked days later after much criticism from the private sector.

In an apparent effort to negotiate for his survival, Castillo convened the leaders of all the parties with representation in Congress for talks before Tuesday, without specifying the agenda. The two largest right-wing parties, Fuerza Popular and Renovación Popular, did not attend. His meeting with Vladimir Cerrón and his former prime minister Guido Bellido, members of the radical faction of Peru Libre — which ultimately did not support the motion to impeach him — have caused some to speculate that Castillo will tilt back towards the far left, because of the right’s determination to remove him. But that will neither empower nor weaken him. Castillo’s real problem seems to be that he seems uninterested in governing, and instead seems focused on using his position to favor his allies, and perhaps himself. His defenders would argue that that makes him no different to past Peruvian presidents, but that is precisely the issue: Far from bringing about real change, Castillo is continuing the most traditional aspects of Peruvian politics.

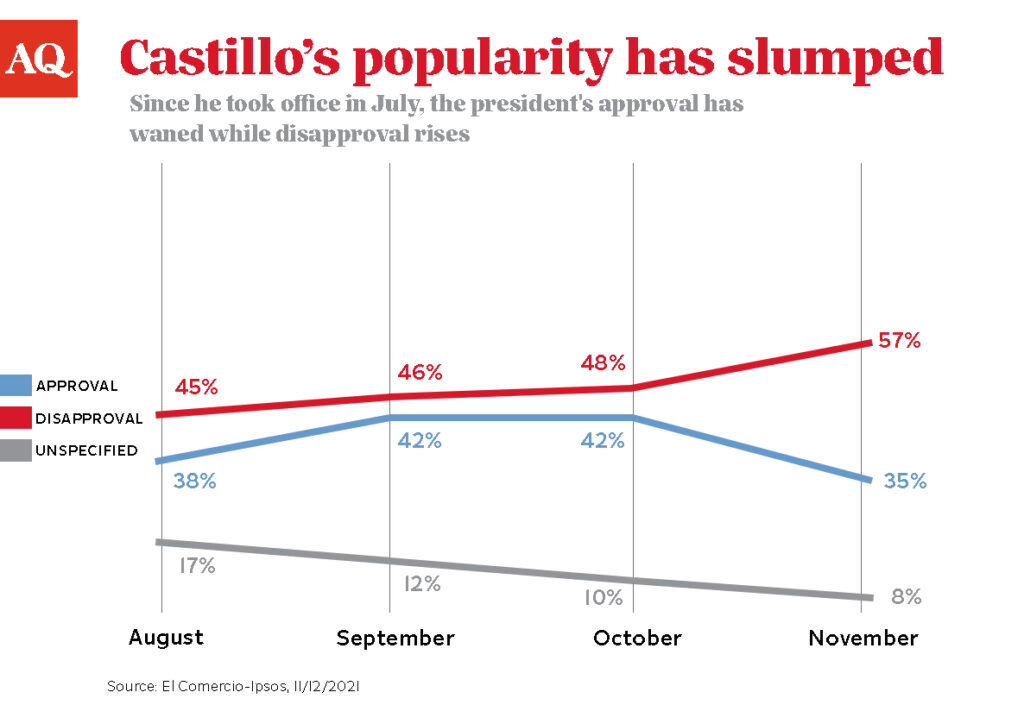

Meanwhile, the opposition will bide their time. They have held back on this occasion, but not out of real concern for democratic stability, nor, it is clear, out of any tacit support for Castillo. The right has simply learned its lesson from the impeachment and removal of Martín Vizcarra in 2020: So long as the president has some support, attempts to impeach him will result in significant blowback. That is not to say that recent events aren’t hurting Castillo’s approval ratings. He currently has 25% approval, compared to 35% in October, according to pollster IEP, but 55% of the population is still against removing him — probably because Congress has an even worse approval rating of 21%. So the right will wait and watch. Based on his behavior to this point, Castillo will lend them an opportunity to deal him the final blow sooner rather than later.