PUEBLA, Mexico—The fact that the Lebanese-Mexican Center in Puebla seems past its heyday is itself a tribute to the triumph of the diaspora. The Lebanese mostly arrived in Mexico over the first half of the 20th century. Once settled, the community thrived, clinging to its roots via customs, food, family and religion (mostly Maronite Christianity).

The 1960s-era building housing Puebla’s Lebanese-Mexican Center is nowadays frequented by only a handful of greying or white-haired regulars. But it’s not that the Lebanese disappeared from Mexico. Rather, they became Mexico—or Mexico has become them. The melding of cultures has meant that cities like Puebla are awash with tacos árabes and political posters featuring Lebanese last names, like that of Rodrigo Abdala, who is hoping to run for state governor, but where Lebanese identity stops and Mexican identity begins is increasingly tough to parse.

What about Mexico’s next wave of immigrants? On the extremes, the country’s new arrivals are surprisingly similar to their forebears—desperate migrants trapped on their way to the U.S. on one end, moneyed businesspeople who arrived as “expats” but remained as immigrants on the other. But new trends, from cheap flights to digital nomadism, have made today’s migration a very different phenomenon. And the dividing line between migrants who spend time in Mexico but don’t mean to stay, and immigrants who settle there permanently, is considerably blurred.

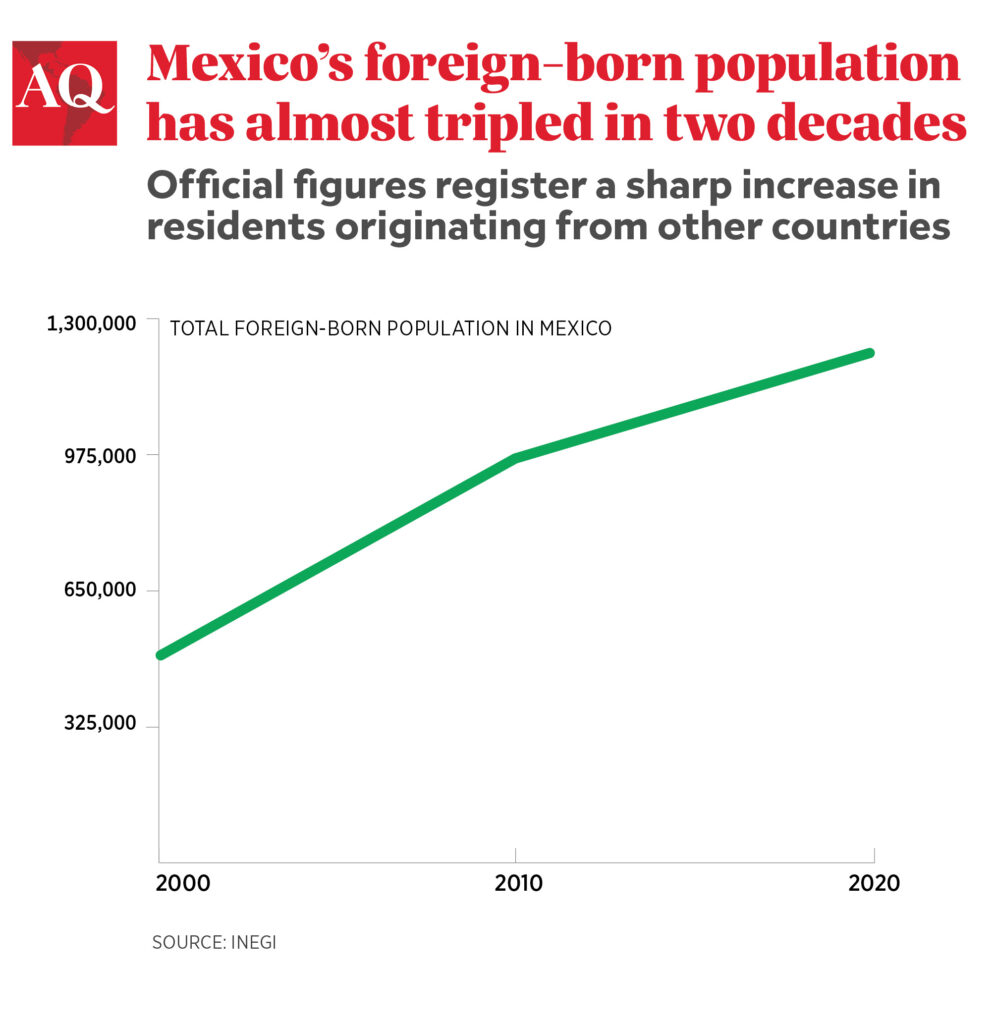

By regional standards, immigration to Mexico this century seems underwhelming. Officially, there are around 1.5 million immigrants in a country of 130 million. But this hides a much bigger migratory story, quantitatively larger and different from before. Mexico’s official figures count fewer U.S. citizens living in Mexico than the U.S. State Department—which suggests their figures may undercount the overall immigrant population.

Though refugees and tourists aren’t categorized as immigrants, often the former can become the latter undetected. What’s clear is that in recent years, the sheer number of people coming to Mexico either as tourists, migrants or refugees has grown enormously. And the effects of migration are more visible than ever.

Millions pass through the country in transit towards the U.S. each year. The vast majority make it to their destination or are returned to their country of origin, but those that end up staying often do not wish to announce it. Some hope against hope that their stay in Mexico is only temporary. Tijuana’s Little Haiti holds thousands of such hopefuls, who are slowly abandoning their hopes of crossing the border and setting up shop in this border town.

Tijuana’s Haitian diaspora services other hopeful Haitians, but they’ve also begun to integrate into the local community. They’ve introduced the city to fritay, a popular dish often made up of fried pork, plantains and pickled vegetables, but also forced the city to confront a deep-seated racism. A not uncommon cause of death for members of the Haitian community is being denied healthcare at local hospitals.

Immigration in disguise

Of the 33.2 million people who visited Mexico in the 12 months following September 2022, a small minority are actually immigrants in disguise, entering and exiting the country perennially to avoid the difficult paperwork needed to obtain residence. A combination of Mexico’s extremely tough residency laws and lax tourism regulations make this a common endeavour—especially in an age in which digital tools have untethered much white-collar work from geography.

Mexico’s position, sandwiched between a region with massive push factors like crime, poverty and the legacy of civil war on one side, and the world’s largest economy on the other, make it a crossroads. “Since at least 2010, 9 out of 10 undocumented migrants have been nationals from … Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, looking to enter the United States,” according to official figures.

And even if many migrants do not intend to make Mexico their final destination, Mexico’s closeness to Central America has inevitably made it a large migratory sink, especially in the south: 58.4% of Mexico’s Guatemalan migrants, 28% of Hondurans, and 25.5% of Salvadorans live in the southern border state of Chiapas, one of Mexico’s poorest.

Upper-middle-class immigrants

Meanwhile, a new group of middle-class professionals looks to capitalize on strategic advantages that might not put them ahead in their own country. A large number of Mexico’s startups have been founded by immigrants, including the Venezuelans behind Kavak (the country’s biggest startup) and the Anglo-Mexican-Bolivian-French founding team of Luuna (a successful ecommerce platform for mattresses).

Mexico’s strange position in the world’s migratory story can make for strange political bedfellows. The Mexican government, purportedly on the left of the political spectrum, dissuades migration by deploying the army to deal with migrants and by extending Mexico’s own cash transfer schemes to Central America to discourage migration.

Among the Mexican population at large, migrant communities stir up a particular mix of Mexican xenophobia and malinchismo, the country’s fabled self-hating preference for all things foreign. In the country’s upscale bars, mostly white Argentines dominate the up-selling industry. Educated Venezuelans, now Mexico’s second largest migrant group, are paid a pittance to serve U.S. tourists in fluent English, irking locals who are suddenly prone to blaming migrants for the country’s ills.

Despite the challenges, entrepreneurial immigrants create distinctive communities along the way. A few years ago, Tek Yang gave up a corporate job at Samsung to try his luck catering to the growing ranks of his compatriots. The Korean community near Samsung’s Mexico City headquarters was too well established, but the arrival of Kia in the northern city of Monterrey seemed like the perfect place to start anew. “I decided to open a Korean restaurant and bar, focused on both Mexican and Korean customers,” Yang said.

In a recent book, the writer (and soccer fan) Juan Villoro recounts how he was shocked to find a large gathering of Japanese fans at a match played by his beloved provincial Necaxa Football Club. The reasons, he explained, were twofold: Firstly, the team’s hometown of Aguascalientes is also home to Nissan’s main Mexican manufacturing plants. And secondly, the red and white of Japan’s flag are also worn by Necaxa’s players on the field. A serendipitous home away from home.

__

González Ormerod is a Mexico City-based editor, writer and historian of Latin America