Javier Milei campaigned on two key promises: To bring the country’s high and accelerating inflation to a halt by dollarizing the economy and closing down the Argentine central bank (BCRA), and to balance the budget by taking a chainsaw to wasteful government spending.

Now, 15 months into his term in office, he has made heroic progress on the fiscal and inflation fronts. But by forsaking dollarization and keeping currency and capital controls in place, Milei has jeopardized his anti-inflationary program and discouraged a potential investment boom.

In the three weeks between Milei’s victory and when he took office in December 2023, he apparently experienced a change of heart. Originally set on appointing dollarization champion Emilio Ocampo to head and shutter the BCRA, and his friend Luis Caputo to be the chainsaw-wielding economy minister, Milei was persuaded to do otherwise by his political advisors because he would not have the necessary congressional support.

Milei thus picked Santiago Bausili, Caputo’s close and like-minded friend, to head the BCRA, and the dollarization proposal soon became a pledge that, eventually, pesos and dollars would be allowed to circulate freely in Argentina at values set by the market.

To compensate for the lack of a dollarization anchor, Milei set about putting an end to fiscal deficits starting immediately, which required finding savings equivalent to an impressive 6% of GDP. Within days, Caputo announced deep cuts to salaries, pensions, public works, transfers to provinces, and subsidies to consumers of utilities and transport services.

In parallel, Bausili stopped issuing the costly short-term securities—the infamous LELIQs—that had ballooned out of control and were jeopardizing the BCRA’s ability to curb monetary growth, while the quick fiscal turnaround allowed him to halt all lending to the government.

A web of currency, trade and capital controls

President Milei inherited a Kafkaesque regime of quantitative controls on exports and imports, cross-border payments and receipts, and capital inflows and outflows. The regime included a dozen discriminatory exchange rates plus multiple taxes on international transactions. Beef and livestock exports were capped; dollars earned from wheat exports were taxed differently from soybean exports; and dollars supplied to cover shipping costs were taxed differently from those to pay for foreign professional services.

On the eve of Milei’s inauguration, the official exchange rate for pesos was grossly out of line with market realities, nearly a third of the unregulated rate. Having discarded dollarization, and in light of President Milei’s libertarian ideology, many expected his administration to move swiftly to dismantle this complex, dysfunctional, and unpopular web of currency, trade, and capital controls. Milei had pledged that once the fiscal deficit was eliminated and the BCRA was rehabilitated, the government would start lifting import and capital controls and unifying the country’s multiple exchange rates.

Instead, Milei opted for a 54%, one-time adjustment in the official rate in December 2023, followed by additional monthly devaluations of just 2%. Other than committing to eliminating an opaque system of controls for access to dollars for imports, there was no pledge to deconstruct the complex web of discriminatory restrictions, taxes, and other interventions that have long soured Argentina’s business climate and isolated the country from international markets and investors.

Back to the future on exchange rate policy?

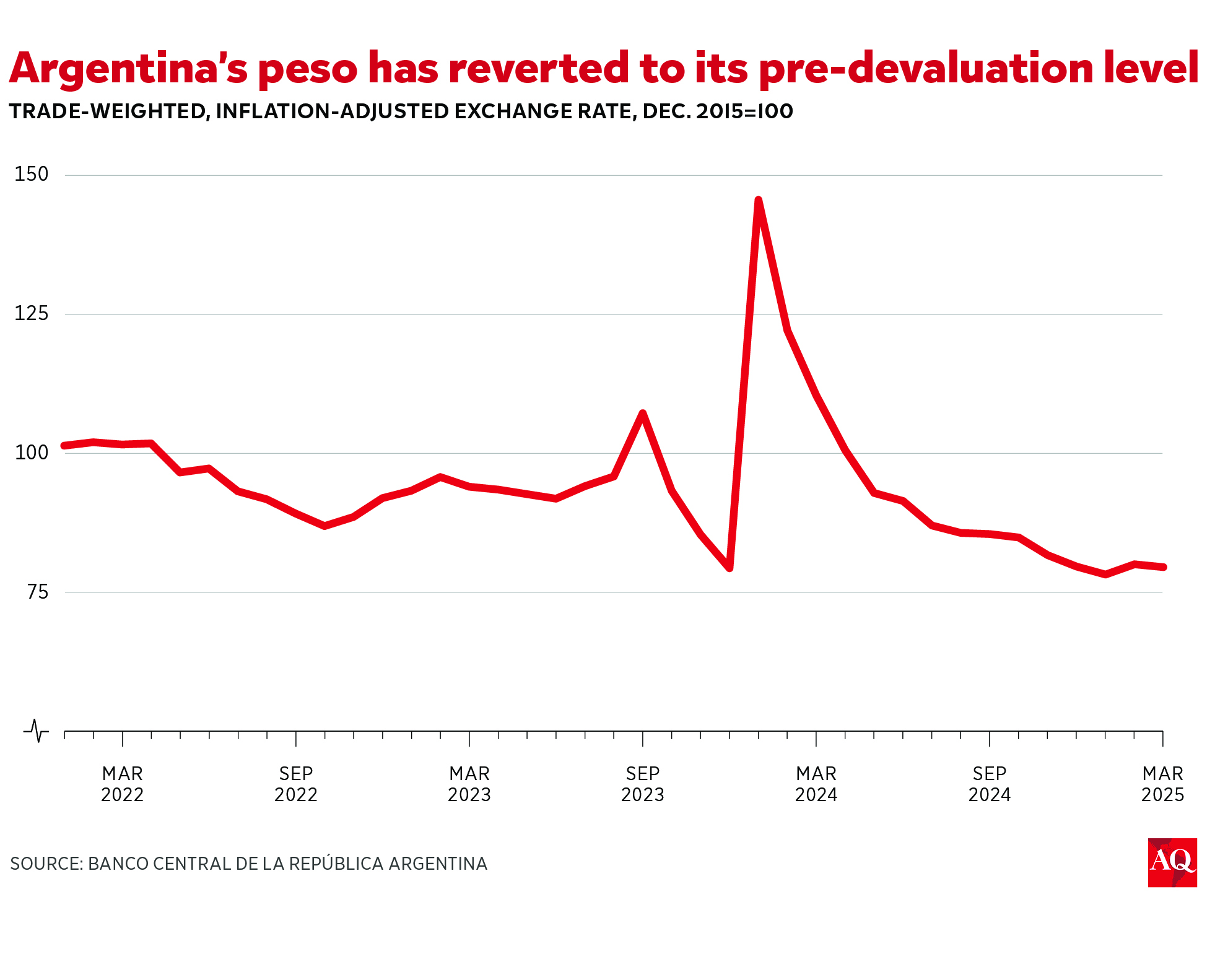

Milei’s commitment to monthly devaluations totaling 28% in 2024 was intended to help anchor inflation expectations, complementing the effect of the commitment to a balanced budget. It was a risky gamble: At the start, the consensus forecast was that 2024 inflation would exceed 200%. In the end, last year’s inflation rate was 118%, much better than expected and slower than 211% in 2023—but too high relative to the currency devaluations. Consequently, the peso has become just as overvalued as it was on Inauguration Day.

The currency is still on course to become more overvalued this year because the authorities have recently doubled down on the exchange rate to anchor inflation expectations. As of February, the pace of monthly devaluations has been reduced to 1% from 2% despite inflation still running above 2% per month, notwithstanding a consensus forecast of 23% inflation this year, twice the anticipated pace of currency devaluation.

The now high cost of Argentine goods and services once translated into dollars is illustrated by the fact that a Big Mac is nearly 60% more expensive in Argentina than in the United States, whereas a year ago, it was 13% cheaper. This is having predictable consequences. Imports of goods, and payments on imports, including credit-card charges in dollars, are surging. Argentines are flocking to Brazil and Chile because shopping and holidays are now a bargain, while tourists from all neighboring countries have cut back on their travels to expensive Argentina. Soccer players that previously left Argentina attracted by lucrative contracts overseas are either coming back or not leaving because now they can get equivalent offers.

Equally worrisome is that the promise to devalue the peso reliably by 2% or even 1% per month has encouraged a wave of “carry trade”—namely, unhedged and thus risky—investments in Argentina prone to be unwound in destabilizing fashion should doubts arise about that promise. While interest rates in Argentina have not been high relative to inflation, they have been high enough relative to the slow crawl of currency devaluations, so companies that earn or can borrow dollars have been reaping the higher returns offered by peso investments. Given that President Milei has pledged that currency and capital controls will be relaxed after the October midterm congressional elections, an unwinding of the carry trade in the months to come looks likely—and could be messy.

The economic history of Argentina and the rest of Latin America is littered with failed experiments in controlling inflation with an exchange rate anchor. President Milei and Minister Caputo claim that the fact that they have eliminated the fiscal deficit guarantees that this time will be different. But the Chilean government had to break its fixed exchange rate in 1982 even though it ran budget surpluses in the preceding years, and the same happened in Mexico in 1994 in the aftermath of four years of fiscal surpluses.

The Argentine authorities are currently finalizing negotiations on a new and large loan program with the International Monetary Fund. Whether the Fund will agree to lend Argentina dollars that may be used to prop up a fragile and harmful exchange rate regime remains to be seen.