This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on cybersecurity

In the heart of Panama City’s historic Casco Viejo district lies a tiny museum dedicated to the history and cultural importance of the mola. This intricate and vibrant handmade textile is part of the Guna Yala woman’s traditional dress and dates back to the 19th century. Today, it is a tie that binds together their culture, history, language and economy, as the Guna Yala face a new trial—becoming one of the first native communities in Latin America to be forced to relocate due to climate change.

The Guna Yala people originate from northwest Colombia and Panama’s Darién province. Conflict with other Indigenous groups between 1850 and 1890 forced most Gunas to migrate westward to the San Blas Islands, an archipelago off the north coast of Panama. There, the Gunas gained access to industrial products such as fabric, thread, needles and scissors. Women began transferring the traditional geometric designs that they painted on their bodies onto cloth.

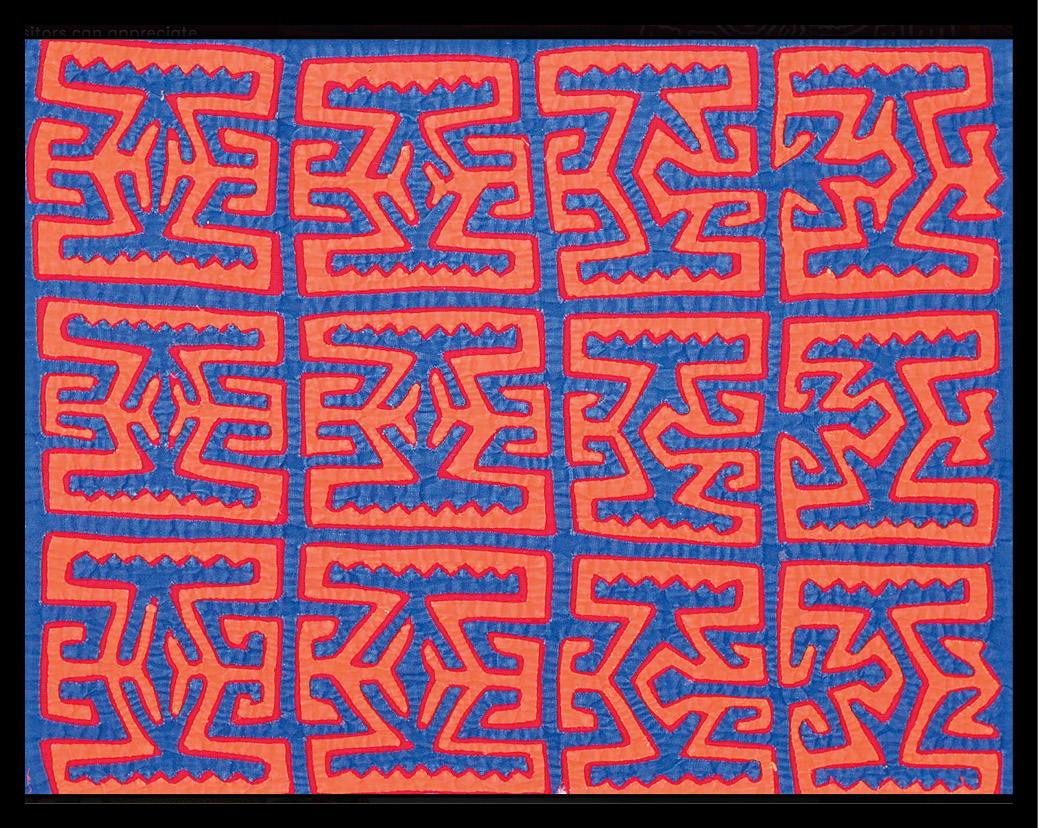

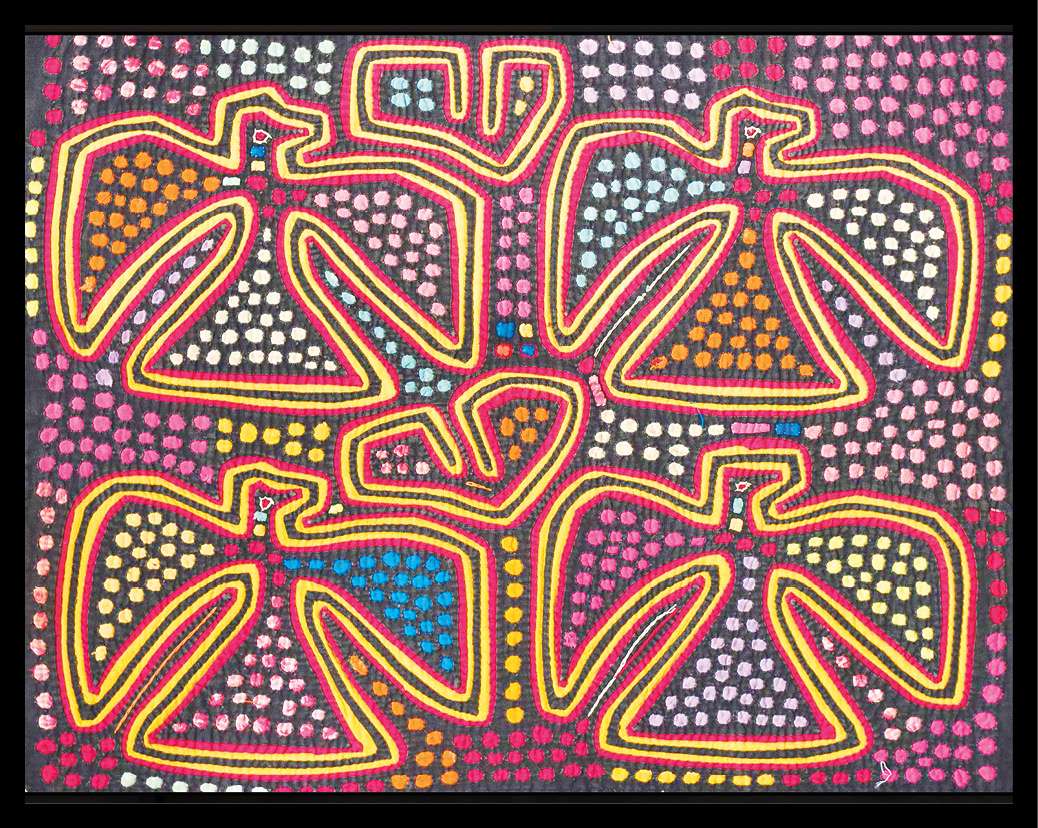

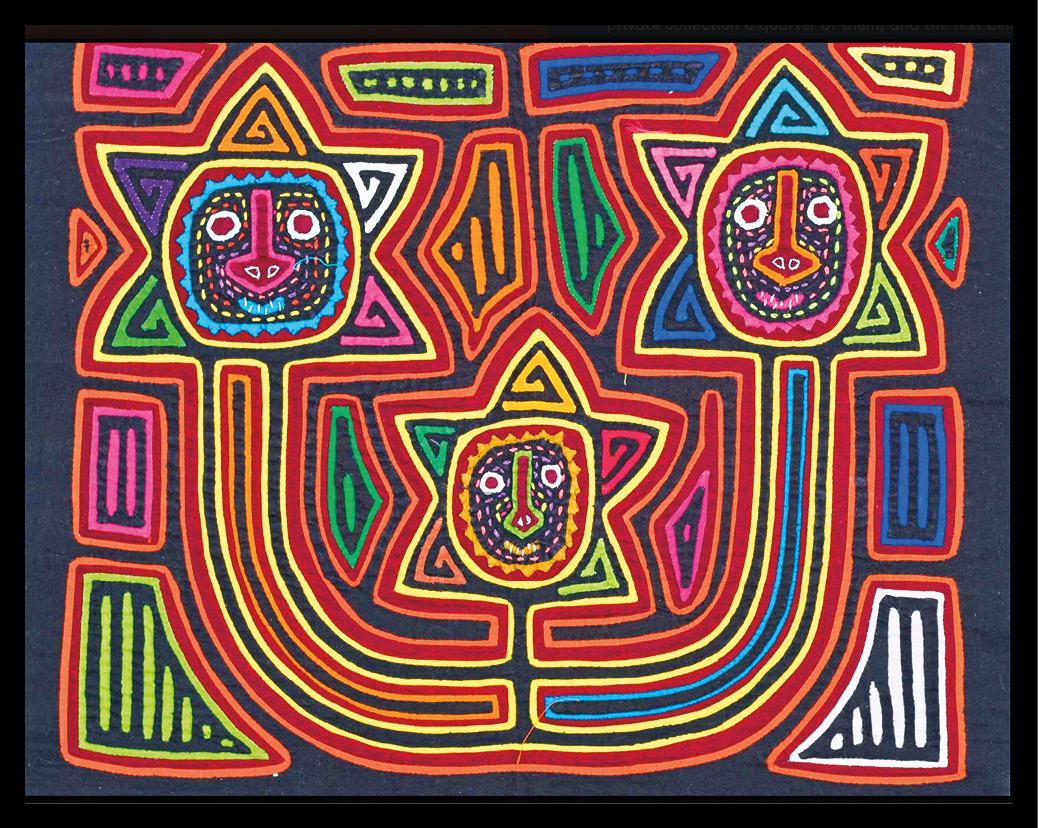

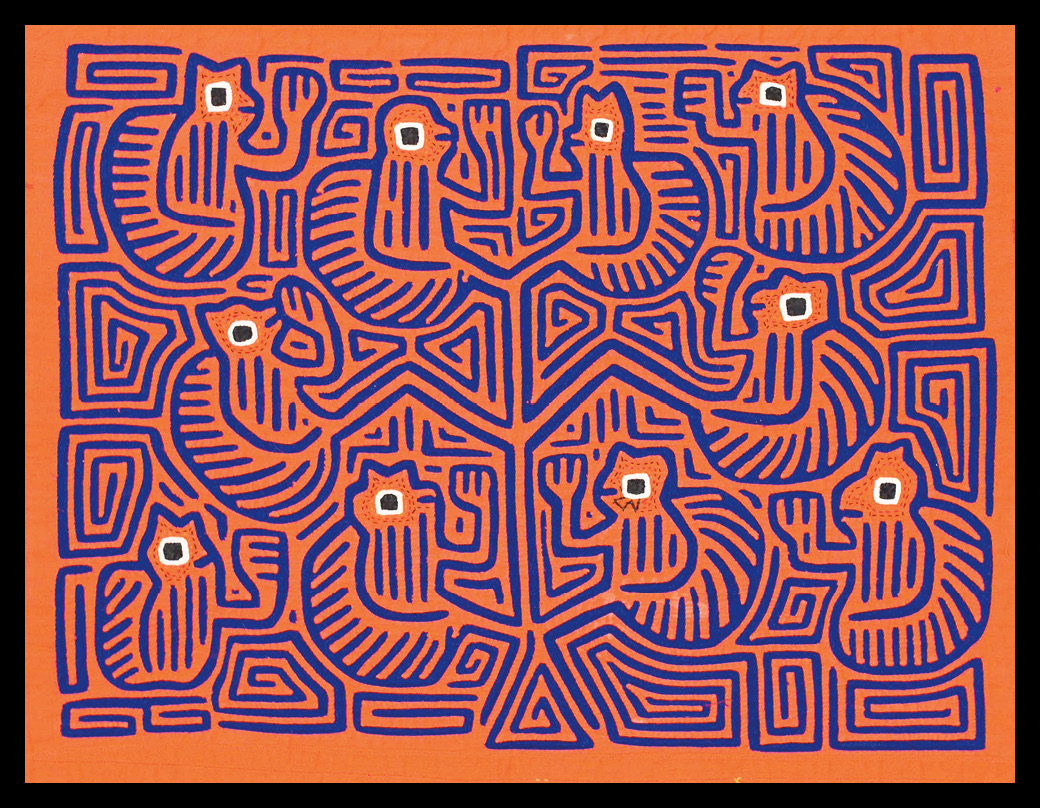

Guna women spend approximately 60 hours making one mola, sewing together up to seven layers of multicolored fabric. An intricate design—either a geometric pattern or an element of nature, such as a bird or flower—is then revealed by cutting out parts of each layer, in what’s known as a reverse appliqué technique. According to Guna traditional beliefs, the resulting three-dimensional effects merge reality and the supernatural, protecting the women who wear the garments.

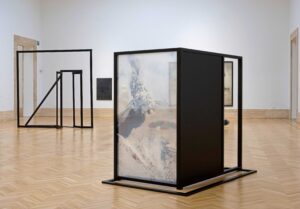

More than 200 molas are exhibited in the Museo de la Mola, opened in 2019 as a showcase for these textiles and the skill of the women who sew them. Gunas have become internationally known for their molas, which represent a significant source of income for communities that otherwise depend on handicrafts, fishing, tourism and trade. But as sea levels rise in the low-elevation Caribbean archipelago, Guna livelihoods have come under threat. This year, the Panamanian government has put a plan in place to relocate 300 families from Gardí Subdug, or Crab Island, to a housing complex on the mainland, just a 15-minute boat ride from the island.

Between 1907 and 2000, sea level rise on the San Blas archipelago averaged 2.0 millimeters annually. Now the rate has risen to 3.5. By 2050, scientists predict, the islands will be completely underwater.

Museo de la Mola

Permanent collection

Though they will have the chance to own land on the mainland, Gunas fear their ethnic and cultural identities will not be preserved once they are living in the bland housing complex with rows and rows of identical houses. And rightly so. They’ve lived on the Caribbean islands for centuries, enjoying autonomous jurisdiction over them since 1925, when the Guna Revolution took place. The revolution was in response to failed attempts by the Panamanian government to strip away the communities’ cultures and traditions through assimilation, including preventing Guna women from wearing their traditional dress. Gunas resisted, rising up against the Panamanian police and government in a three-day uprising that resulted in 27 deaths. A peace agreement mediated by the United States guaranteed respect for the Gunas’ traditions and culture.

On the mainland, Gunas will also need to diversify their economy away from fishing and trade. Faced with this new reality, molas will continue to serve as a source of income and, perhaps more importantly, a way of keeping the Guna culture and traditions alive. For Gunas, molas are a form of writing. On fabric, Guna women portray the peoples’ reality. As one description on the walls of the Museo de la Mola puts it, “By creating molas, the Guna woman writes down her community’s worldview and history, preserving them forever.”

—

Guevara is a policy analyst and a legislative advisor in the National Assembly of Panama