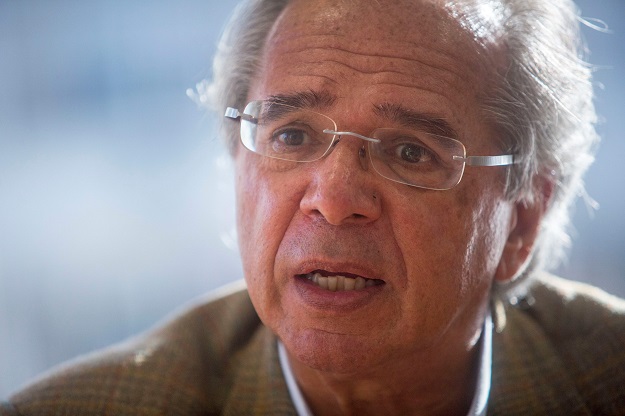

Early in his career, fresh from his 1979 Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, Paulo Guedes had a brief stint as a teacher at the Universidad de Chile. The country’s economy was undergoing a deep transformation at the hands of fellow Chicago Boys, as the economists from his alma mater became known. Guedes didn’t stay long, but all around him was what Milton Friedman called the “miracle of Chile”. He did not form ties with the Chilean political establishment and has rejected any association with the regime of Augusto Pinochet. To piauí magazine he stated that “I knew there was a dictatorship, but for me this was irrelevant from an intellectual standpoint.”

This was decades ago, but the link to today resides in his vision for Brazil’s economy. Guedes may now have a chance to lead his own dramatic neoliberal economic transformation. As the likely finance minister under Brazil’s President-elect Jair Bolsonaro, Guedes will be charged with reviving an economy still struggling after a 2014-16 recession that was the worst in Brazil’s modern history. “Reforming the pension system is priority number one,” he said to reporters the Friday before the election. “In second place comes lowering the debt, we will accelerate privatizations and cut our interest payments” mentioning a yearly bill of $100 billion. He has said that selling off entities such as Petrobras, Eletrobras, Banco do Brasil and Caixa Econômica Federal could bring close to 1 trillion reais (about $270 billion) in revenues.

His priorities list also includes reducing government spending and taxes, all of which was music to investors’ ears. Guedes provided “instant credibility” to the then-candidate, said Thomas Trebat, director of Columbia University’s Global Center in Rio de Janeiro. “He represents the first chance for Brazil to try a radical form of a free market economy,” Trebat said.

Will he succeed?

Many people in the financial sector praise his intellect. “He’s brilliant”, said a market source that spoke to AQ on condition of anonymity, while highlighting that his hot temper might hinder his efficacy. Other sources also questioned whether he will have full support from Bolsonaro or from the more statist-minded members of his circle, which includes several retired military officers, such as Vice President-elect Hamilton Mourão.

Market participants are excited about his policies but concerned about his lack of political experience since he will have to negotiate with a congress made up of political novices. One senior banker said that Guedes “does not understand the subtleties of implementing his policies”.

Guedes is a political newcomer, having been in the private sector since the early 1980s. A fixture in financial markets, he was the co-founder of Banco Pactual (precursor of BTG Pactual) in 1983, later opened BR Investimentos, now part of Bozano Investimentos, helped set up business school Ibmec, later sold to DeVry, co-founded economic think tank Instituto Millenium and invested heavily in education groups.

Long time coming

“I suggested selling everything in 1989,” Guedes told Reuters, saying that privatizing all state companies would have erased the national debt. “The last 30 years were a disaster – we corrupted democracy and stagnated the economy,” Guedes told Bloomberg in an interview published in April, adding, “we should’ve done what the Chicago Boys instructed,” following a recipe of deregulation, privatization and free-market principles.

Bolsonaro and Guedes are an unexpected pairing. They met while the economist was advising another candidate during Brazil’s prolonged presidential campaign. Guedes only joined the former army captain after TV presenter Luciano Huck decided not to run.

Bolsonaro supported corporatist policies during his 27-year congressional career and voted against privatizations and pension reforms, but the president-elect has also admitted that he “does not understand economics,” and during the campaign deferred all questions about it to Guedes. Sources say Guedes sees his partnership with Bolsonaro as a chance to implement his vision, although the two have publicly clashed and contradicted each other. In late September, Guedes floated the idea of reinstating an unpopular financial transactions tax, prompting Bolsonaro to deny and shun the idea. The President-elect also pushed back on privatization plans, saying that Petrobras and Eletrobras would not be fully privatized.

This history of policy confusion has some observers doubting that Guedes will stay in Bolsonaro’s cabinet for the long term. Monica de Bolle, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and the director of the Latin American Studies Program and Emerging Markets Specialization at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University, and a frequent Bolsonaro critic, expects that Guedes will last only three to four months in office.

Last hurdles

Two recent investigations into Guedes’ businesses could also disrupt the potential minister’s plans. The Public Prosecutor’s Office is looking into Guedes’ role in alleged fraud and excessive charges over management of assets belonging to pension funds. Guedes denies any wrongdoing and claims the investigation was designed to confuse voters. He is expected to testify in Brasília on November 6.

If legal woes don’t stop him, Guedes may help usher Brazil into a new era of neoliberal economic policies. Only the jury is out on whether his political inexperience and mercurial temperament will allow the Chicago Boy to stay long enough to enforce the free-market policies that attracted Brazil’s private sector to Bolsonaro in the first place.

—

Sweigart is a policy consultant at Americas Quarterly