This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on trends to watch in Latin America in 2025.

In her latest book, which levels a critique against “progressive feminism,” Argentine novelist Pola Oloixarac recounts an episode of brutal gender violence that took place in her own family. Her great-aunt Ana was beaten to death at her doorstep by her boyfriend, in front of her neighbors, in Lima in 1956.

Stories like this one remain common in Latin America—and have galvanized feminist movements to take to the streets. Oloixarac acknowledges the severity of gender violence in Latin America, but in Bad hombre, a “work of fiction about real events,” her attention is mostly directed at a different phenomenon: the reckoning over sexual harassment and assault that spread through workplaces and social circles across the globe in the wake of the #MeToo movement in the U.S.

In doing so, Oloixarac makes the provocative allegation that elite women exploit feminism to serve their own personal interests. “Is it fair,” she writes, “to use Ana’s suffering and those of so many murdered women as a virtuous alibi that conceals personal revenge?”

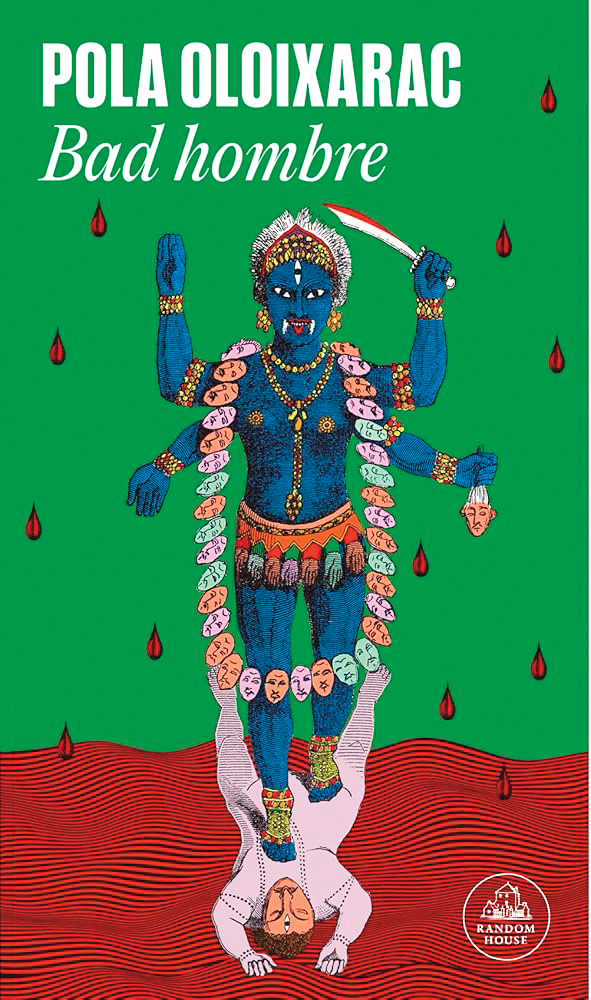

Bad hombre

Pola Oloixarac

Literatura Random House

Paperback

224 pages

Between 2016 and 2018, Oloixarac says she was approached by women who wanted to punish certain men by accusing them of sexual misconduct, inviting the author to join them in their cause; their stories form the basis of the book. In Oloixarac’s telling, the men had perhaps been careless in their behavior, but none of them had committed any crime. The women knew that by declaring they were victims of violence, they could cast a shadow on these men that others would not question, out of fear of being punished themselves for not upholding a mandate in their social circles: to believe women.

In short, these men were “canceled,” not out of authentic concern for women’s rights, but for the personal gain of the accusers. This is the central thesis of Bad hombre: Elites weaponize their own language to “purge what no longer serves them,” writes Oloixarac. In some of the stories she narrates, women are treated badly, but others are about “cancellations” driven entirely by professional envy.

There’s Laurent, a university professor in France who, shortly after having an online affair with a woman he never actually meets, is anonymously accused of sexual misconduct and loses his job, just as he was coming up for tenure. David, a successful and charming Colombian writer in the U.S., is ostracized by his literary friends and colleagues after one of them spreads the word that he raped a former girlfriend, despite the girlfriend in question insisting that no rape took place.

Bad hombre is mainly an exploration of “elite capture,” the phenomenon coined by the philosopher Olufemi O. Taiwo. Taiwo argues that legitimate grievances such as sexism and racism are exploited by those in power to serve their own narrow interests—like getting rid of rivals. It’s telling that Oloixarac’s protagonists are all academics, writers and journalists: These are influential people. The stories she tells are quite familiar in these circles in Latin America, which makes Bad hombre a very engrossing read. Ask a Peruvian writer, a Uruguayan journalist, a Brazilian academic—they most likely have witnessed similar cases in recent years.

But where Oloixarac falls short is in failing to offer a broader commentary on the very persistent and troubling phenomenon of sexual violence in Latin America. Significant awareness has been raised in the last decade by feminist movements like #NiUnaMenos, which took off first in Argentina in 2015 and then spread to other countries. But women still die every day, mostly at the hands of the men in their lives. In 2022, according to the UN, at least 4,050 women were victims of femicide in the 26 countries that make up the region.

It’s not difficult to find examples that suggest political correctness has gotten out of hand in the elite worlds of literature and academia. However, Bad hombre runs the risk of trivializing, or worse, delegitimizing the importance of what Oloixarac wants to prevent in the first place: women’s suffering.