This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on trends to watch in Latin America in 2025

In some towns on the border between Brazil and Bolivia there’s a slight feeling of bitterness among Bolivians towards their Brazilian neighbors. An old debt is due.

Latin Americans are eager to see more regional integration—70% of them are in favor of that. But although Brazil borders every country in South America except for two (Ecuador and Chile), it has often struggled to truly engage with them—perhaps because of linguistic differences, or the fact that the borders themselves, often located in the Amazon, make greater connectivity more difficult.

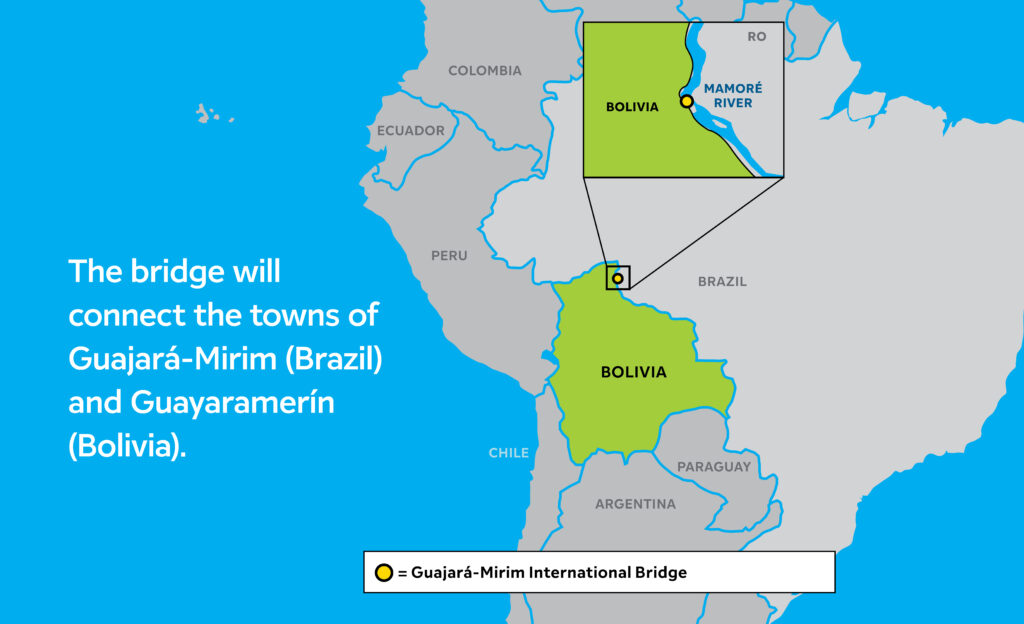

In light of those difficulties, it’s relevant that Brazil seems poised to deliver on a very old project: the construction of a new bridge between Guajará-Mirim (Brazil) and Guayaramerín (Bolivia), expected to be completed in 2027 at an estimated cost of $70 million.

The question is: Why now? The Mamoré International Bridge was supposed to be built 121 years ago, as part of a deal between Brazil and Bolivia in which the latter agreed to give up part of its territory. Never completed, today the bridge may finally become reality, but for a very different reason: It is part of a wider plan to develop infrastructure that would open paths for Brazilian commodities to the Pacific Ocean.

“We are beginning a new era in Brazil-Bolivia relations,” Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said during a visit to Bolivia in July 2024. “We are convinced that integration is no longer just rhetoric for election campaign speeches. Integration is a necessity for the survival of South American countries.”

The history of the project helps illustrate why regional integration in South America, while frequently presented as a lofty political goal, has proved so difficult over time.

And its present iteration suggests the extent to which Latin American leaders see integration as a way of connecting not only with each other, but with Asia.

A sour deal

In the first years of the 20th century the northwestern Amazon region of Brazil, where the state of Acre is now, belonged to Bolivia— but around 100,000 Brazilians lived in the area. Particularly rich in rubber trees, for years it attracted Brazilian rubber tappers eager to exploit its natural wealth.

Bolivian maps described that part of the Amazon as tierras non descubiertas—undiscovered lands. But as European and North American demand for rubber grew, Bolivia started to stake its claim.

In 1899, the Bolivian government set up a customs office in Puerto Alonso, which today is called Porto Acre, and entered a deal with the U.S.-based consortium Bolivian Syndicate, giving them the right to produce and export rubber, collect taxes and act as a police force. It was a way the Bolivians found to gain back control of the territory.

The Brazilian residents were furious. Armed rubber tappers expelled the Bolivian Army in the Acrean Revolution (1902-03), and twice tried to set up an independent republic.

Things had gotten out of hand. Brazil’s republic, only 14 years old at the time, had to that point not challenged Bolivia’s official claim of the territory of Acre. Faced with rebellious citizens, it decided to defend a negotiated solution in which Acre would be incorporated into Brazilian maps.

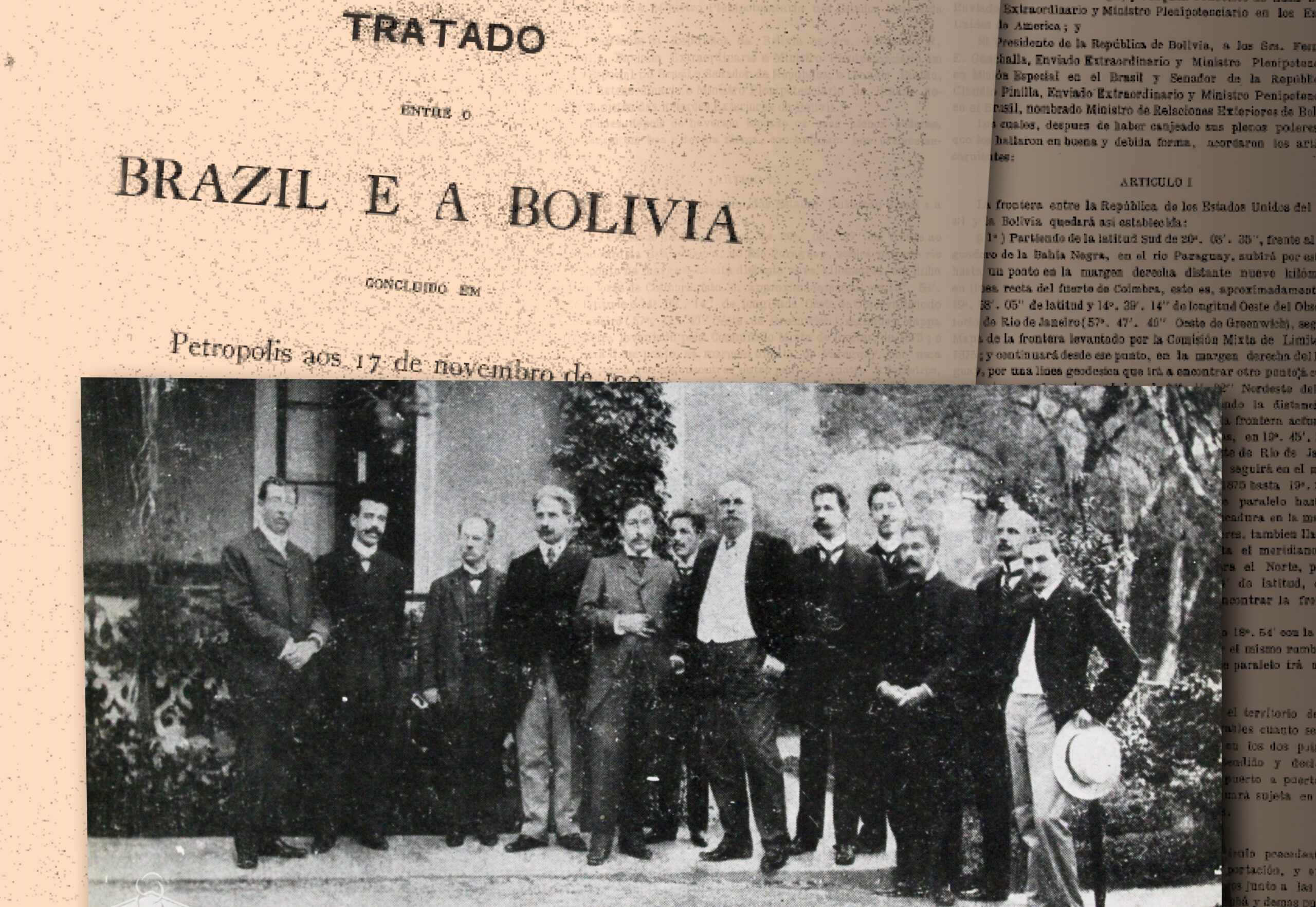

Brazilian and Bolivian diplomats met in Petrópolis, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, to talk it through, and the Treaty of Petrópolis was signed on November 17, 1903. Per the agreement, Brazil annexed the Acre region—it is no coincidence that the state’s capital, Rio Branco, is named after the Brazilian diplomat who led the negotiations, José Maria da Silva Paranhos do Rio Branco. So as not to sour relations with Bolivia, in exchange, Brazil would grant their neighbors land in the Paraguay River Basin, 2 million British pounds and the commitment to build a railway cutting across the Amazon to facilitate Bolivian access to the Atlantic Ocean. A bridge would complement the project.

Despite huge financial and human costs (construction of the railroad cost an estimated 6,000 lives), the railway was eventually completed in 1912. But the Treaty of Petrópolis has aged bitterly for Bolivians. With the end of the rubber boom, the railway’s relevance diminished and it was abandoned in 1972—along with much of Brazil’s railway network, which was dropped in favor of highways. The bridge was never built.

“From Bolivia’s perspective, it had lost a resource-rich territory, Acre, an important source of rubber at a time of high global demand. The goal of the railway, to give Bolivia the right of free transit, although partially realized, was limited over time. All of this reinforced the sense that Bolivia had lost a valuable opportunity for economic development, as the ceded territory to Brazil progressed at a faster rate than Bolivia’s Amazon region,” said Regiane Bressan, associate professor in the International Relations Program at the Federal University of São Paulo—Unifesp.

The memory of the deal is still fresh in the minds of those who live in border towns in the rubber-producing region of the Amazon. “The bridge today is seen as Brazil finally honoring its debt to Bolivians. This is something you hear in everyday conversation with regular people in the streets,” said Marta Cerqueira Melo, an expert on Latin American political economy and integration who has spent the past few years developing her PhD thesis in that very frontier region.

Picking a project back up from the shelf

The bridge project was left in limbo for decades, despite repeated attempts by the Bolivian government to revive it. In 2007, under Lula in Brazil and Evo Morales in Bolivia, who were ideologically aligned, Brazil agreed to pay for the bridge.

Between 2020 and 2023, the current Bolivian government wrote to then-Brazilian president, conservative Jair Bolsonaro, monthly to try to push construction forward. Although the idea of building infrastructure in the Amazon was in line with Bolsonaro’s project for economic development, nothing was done, perhaps due to the leftist nature of Bolivia’s government—the success of regional integration in Latin America, it is often said, depends on ideological alignment between governments.

When Lula came back into office for a third term in 2022, he began implementing the South American Integration Routes project, which aims to connect the continent’s countries to both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Construction of the Mamoré International Bridge is set to begin in the second half of 2025 and details of the tender are still being finalized as of January. When it is operational, Brazilian commodities will have a faster way to access the Pacific Ocean, passing through Bolivian territory to reach Chilean ports on their way to Asia. And Bolivians will get what was agreed in the Treaty of Petrópolis, better access to the Atlantic Ocean through Brazilian territory.

“We are working to establish maritime integration, railway integration, and road integration so that Bolivia can access the Pacific, the Atlantic, and Brazil can access the Pacific. In other words, we want to open our continent to the world and participate in its development,” said Lula after a meeting with his Bolivian counterpart, Luis Arce, in July.

“These infrastructure projects strengthen the notion of greater proximity between Brazil and neighboring countries. In border regions, integration isn’t just a concept—it’s a daily lived experience. So they are important. However, South American integration has assumed a perspective strictly oriented toward Brazilian foreign trade, especially with Asia. Historically, the Atlantic dictated global politics. Today there’s been a shift toward the Asia-Pacific region, where Brazil has a market. So the notion of South American integration has been impoverished, catering almost exclusively to the interests of Brazil’s agro-export sector,” Cerqueira Melo told AQ.

The bridge also exposes inherent contradictions and tensions in Lula’s political and economic project. Elected with the support of environmental and Indigenous movements, the government has had success in halting deforestation in the Amazon, but has pursued infrastructure projects that favor agribusiness in the region.

Cerqueira Melo said another common local concern is crime—on the walls on the Bolivian side of the border one already sees the acronyms of Brazilian organized crime groups. Locals say no strategy has been announced from either side on how to keep that from getting worse.

The Brazil-Bolivia bridge, by connecting the two countries, could, as the original text of the Treaty of Petrópolis stated, “consolidate forever” the “old friendship” and remove “disagreements of ulterior motives,” aiming to “facilitate the development of their commercial and neighborly relations.” But true integration still feels like a more complicated goal to achieve.