Decembers in Argentina are often tense, and not just because of the holidays. In 2001, supermarket riots spilled over into broader street violence, forcing two presidents to resign in rapid succession just before the New Year. Over the past decade, as the economy lurched from one crisis to another, protests again became something of a Christmas tradition.

This year, some observers wondered if the December protests would resume. After all, President Javier Milei has spent his first year in office mercilessly cutting public spending and subsidies on electricity, natural gas, water, and public transportation, living up to his pledge to “chainsaw” the budget. Analysts debated the probability of a “helicopter scenario,” a reference to President Fernando de la Rúa’s December 2001 escape from the besieged Casa Rosada presidential palace.

Instead, Buenos Aires is surprisingly tranquil. Argentines, though not quite upbeat, are emerging from a prolonged period of profound pessimism.

I visited Argentina in April and it was already clear almost everyone had underestimated Milei, including me. Before the presidential run-off, I told The Wall Street Journal that the competition between Milei and the Peronist finance minister was a choice between “someone who can predictably manage Argentina’s decline and someone whose attempts to revolutionize economic management can burn down the house.”

It turns out I was the one blowing smoke. By the time I visited Argentina again in October, Milei’s successes were undeniable. He had beaten the budget into submission, slayed inflation, and did so without igniting social unrest or setting off a paralyzing brawl with organized labor. Inflation, driven by overspending and the wild printing of pesos, had dropped from 25% a month in December to below 3% per month today. The government now spends less than it takes in from taxes. “Country risk,” a measure of bond prices, is at a five-year low, meaning investors are confident they will be repaid.

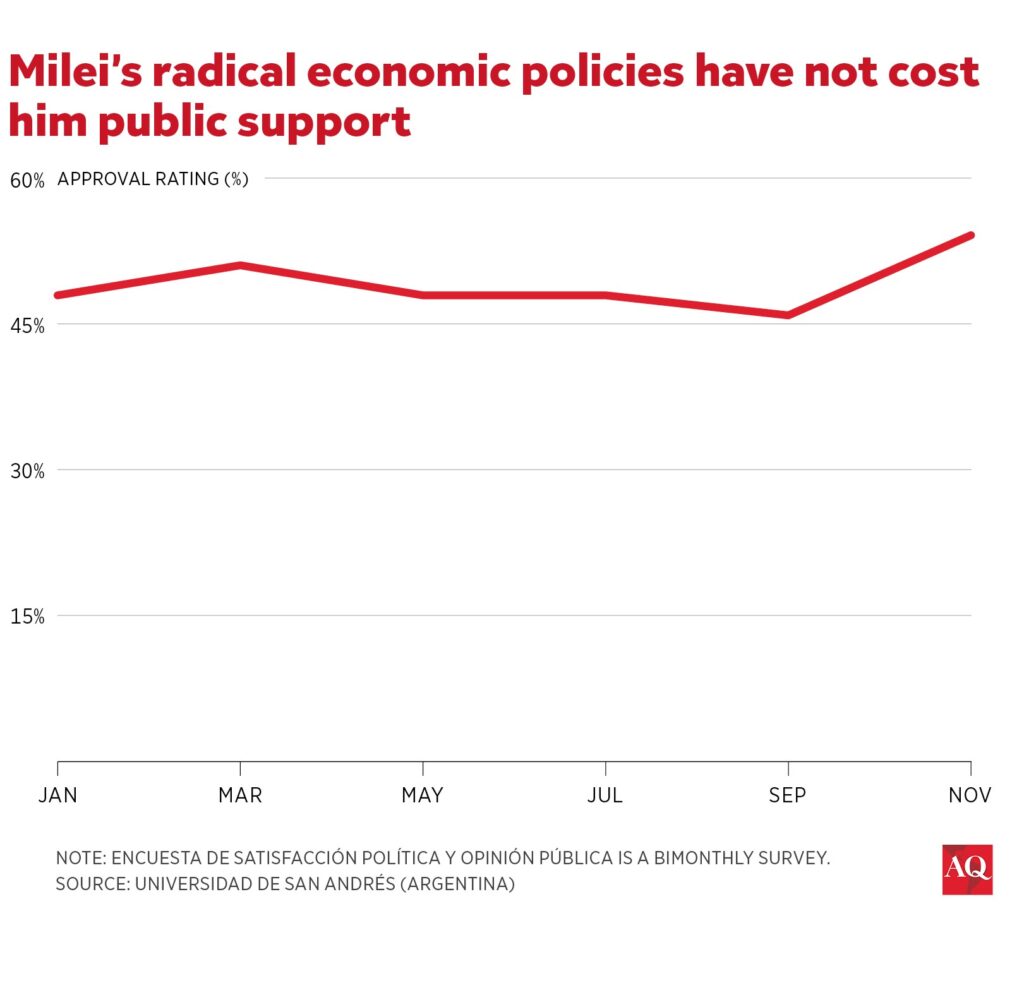

Milei’s radical economic policies hardly cost him public support. In his inaugural address, he warned that “there is no alternative to shock” and a year later, most Argentines apparently agree. In the November Poliarquía survey, Milei registered a 56% approval rating, the exact level of support he attracted in the election. Consumer confidence is rising. There have been several national strikes by confederations of labor unions and two multitudinous protests against spending cuts at public universities. But generally, Argentines are calmly sipping mate.

Why did most of us get Milei wrong? For one, the scale of Argentina’s troubles would have been daunting for a seasoned politician with overwhelming public support, and Milei was none of those things. Before his election to Congress in 2021, he was best known as a shouting TV pundit who had cloned his dogs. In the first round of last year’s election, he won just 30% of the vote. Even Milei voters often described their choice as a salto al vacío, a jump into the void.

Milei’s economic program was more practical than the rest of his platform, including libertarian daydreams to liberalize gun ownership and open a marketplace for human organs. Still, Argentines have a hair-trigger temper when it comes to orthodox economic reforms and it seemed likely the soundtrack of Buenos Aires would once again be the clanging of pots and pans of perpetual protest.

But having sampled the rest of the menu, Argentines proved to be not only willing to elect Milei, but to give him a fighting chance to turn things around. The country had tried everything else, including 16 years of populism–under Néstor Kirchner, his wife, Cristina, and his former chief of staff, Alberto Fernández–and an experiment with gradual pro-market reform that slid rapidly off the rails.

Milei’s shenanigans, meanwhile, now look like a feature, not a bug. The more outlandishly he behaves, the less he resembles the discredited leaders who came before.

Milei’s politics in practice

The presidency has also changed Milei. That is perhaps most obvious in his approach to Congress. His newly established La Libertad Avanza party holds just 39 of 257 seats in Argentina’s Chamber of Deputies, six of 72 seats in the Senate, and zero governorships. In the office of the lower house speaker, Martín Menem, opposite a bust of his uncle, former President Carlos Menem, a map of the chamber color-coded by party seems to guarantee a legislative standstill.

Yet Milei, doctrinaire and combative, has made progress on his dreams of restructuring Argentina’s economy. In June, after six months of public feuding and private dealmaking, he and lawmakers agreed on a major pro-market reform bill that included incentives for companies that invest at least $200 million, the privatization of several state-owned enterprises, and labor reforms.

Milei did not get everything he wished for; Congress, for example, balked at privatizing the national airline and national oil company. Milei recently said his resentment of the government he leads is still “infinite.” Yet after shuttering 11 of 18 ministries, he seems satisfied. His revolutionary zeal no longer extends to dollarization, a mainstay of his campaign stump speech. He has grown comfortable making deals with members of what he derisively calls the “caste,” including Peronist governors.

Things could still go off the rails, as they so often do in Argentina.

Investors are giddy about Milei. But outside the energy and mining sectors, they are not rushing to invest. There are several reasons for that, none of them simple to address.

Many of Milei’s accomplishments are easily reversible and his divisive brand of politics makes it tough to build a durable coalition with the center-right, let alone recruit moderate Peronists. Hard currency reserves are low, making it tough to remove capital controls. The last pro-market experiment, under President Mauricio Macri, ended badly, making it tough to shake the country’s reputation for recurrent crises. (Ditto for unresolved litigation with investors and creditors.) Mercosur is Mercosur, making it tough to open the economy.

Eventually, the Peronist opposition could regroup, challenging Milei in Congress and loosening his monopoly on the national conversation. Either way, the public could grow weary of the shock. Argentina’s economy is expected to shrink by 3.5% this year. Poverty is way up. So is unemployment, now the top voter concern. Pensions are not keeping up with inflation. Should Milei’s popularity decline, his on-again, off-again partnerships in Congress would be off again, perhaps as the October midterm elections approach.

It does not help that Milei picks unnecessary fights. He is admired at Mar-a-Lago and Elon Musk is a fan, but in Argentina, many of his views are miles outside the Overton window. That includes his apparent sympathy for military officers accused of “Dirty War” human rights abuses and his admiration for Margaret Thatcher and apparently limited enthusiasm for Argentina’s claims over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands.

When it comes to budget cuts, the International Monetary Fund gives Milei mixed reviews. It is anxious for Argentina to do away with capital controls and has urged Milei to make sure budget cuts “do not fall disproportionately on working families.” There are also concerns that pulling the plug on public works harms long-term productivity and competitiveness. Amid rising tensions, the IMF in September sidelined its number-one Latin America official from negotiations with its number-one borrower.

Still, given the depth of the hole Argentina had dug itself into, it is not surprising Milei remains subterranean after 12 months in power. Indeed, it is remarkable how close to the surface he has come.