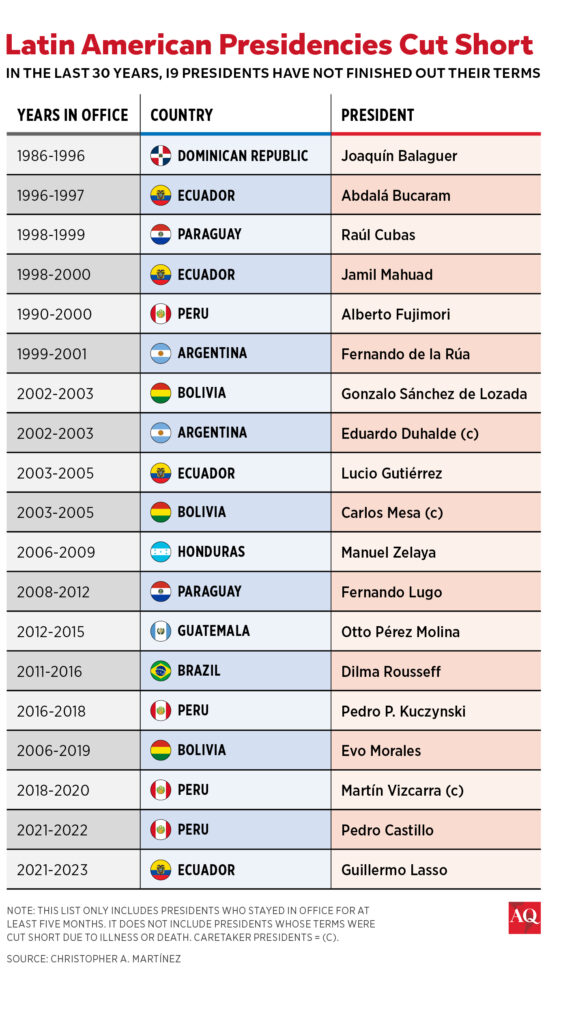

CONCEPCIÓN, Chile — In Latin America, finishing a presidency is still an achievement in itself: More than 20 presidents have failed to do so since the early 1980s. In recent years, Guillermo Lasso of Ecuador and Pedro Castillo of Peru saw their mandates cut short. Argentina’s Javier Milei recently had an impeachment motion filed against him, though it had almost no chance of succeeding. Peru’s Dina Boluarte has so far dodged five motions to oust her by the opposition in a deeply fragmented Congress.

Why do some presidents withstand turmoil while others fall? As I outline in my new book, the key seems to lie in the strength of political parties: When a country’s parties are very strong or very weak, presidencies often survive. It’s when they’re in the middle that alliances become fragile, ambitions short-sighted, and the fate of a president can hang by a thread.

To explain: Presidents can sometimes stay in office when parties are too weak to challenge them. Conversely, while strong parties may have the political strength to remove a sitting president, they may prioritize institutional continuity, even in times of crisis, because they are able to ponder the long-term political consequences of their actions.

When parties aren’t particularly weak or strong, presidents often remain in office due to temporary, unstable alliances. When those alliances collapse, due to a corruption scandal for example, or a presidential grab for power, parties may be both organized enough to challenge a president and lack the long-term perspective to avoid escalating a crisis. That combined poses a higher risk for presidential survival.

Real-world applications

Let’s take Ecuador, Paraguay and Peru, all countries where parties are relatively weak, but where presidents have faced vastly different outcomes. While Rafael Correa (Ecuador) and—for much of his tenure—Alberto Fujimori (Peru) managed to consolidate power, Pedro Castillo (Peru) and Fernando Lugo (Paraguay) saw their presidencies dramatically cut short due to a lack of partisan support, comparatively weak ruling parties, and short-termism.

Where parties are middling in their institutional strength, parties lack long-term horizons and, at the same time, can muster the necessary support to remove a sitting president. The cases of Argentine Peronism in 2001 and the Brazilian opposition in 2016 illustrate that parties can articulate and coordinate with grass-roots organizations and protesters to launch successful attempts to unseat the chief executive. Bolivia only has one strong party, the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) party founded by Evo Morales. This dominance left the opposition weak, preventing effective negotiation and resolution during the November 2019 crisis. As the book shows, the absence of a structured opposition made it impossible for Morales to negotiate or defuse the crisis, contributing to his eventual forced resignation. Without strong and credible adversaries, presidents lack partners for dialogue, increasing the likelihood of abrupt endings.

Conversely, in countries with highly institutionalized parties, like Chile, political organizations have long-term horizons and favor some minimum levels of cooperation. Chilean Senator Jaime Quintana noted that party leaders ultimately align with the president because “the cost of betraying a government to which loyalty was sworn is too high.” This long-term perspective discourages parties from abandoning their leaders during tough times.

Lessons for current leaders in Argentina and Peru

Let’s go back to the initial cases of Javier Milei in Argentina and Dina Boluarte in Peru. Milei, an outsider candidate with a newly formed party, La Libertad Avanza, lacks a majority in Congress. Luckily for him, Milei hasn’t been implicated in scandals, a factor significantly associated with presidential failures. However, as a president of a country with moderate party strength, parties do exist and may successfully curb his power. Specifically, he faces a formidable and organized opposition in the Peronists.

Known for their deep connections to civil society and ability to mobilize protests, the Peronists could significantly challenge Milei’s presidency and bring it to a premature end, especially if Argentina’s economy takes a turn for the worse. Without strong party backing, Milei is vulnerable to both legislative challenges and especially street protests.

On the other hand, Boluarte, also a minority president, has survived multiple waves of anti-government protests and attempts at removal by Congress. The so-called “Rolex case” scandal has taken a toll on Boluarte’s personal approval (she denies wrongdoing), and she is viewed by many Peruvians as an “usurper” due to perceived policy shifts since assuming office after Castillo was ousted following his failed self-coup in 2022.

However, the opposition Boluarte faces is fragmented, and Peru’s economy remains relatively stable. Her survival so far can be attributed to the weakness of opposition parties, but this also means she lacks strong partners to govern effectively. Past Peruvian presidents like Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and Martín Vizcarra were removed despite favorable economic conditions, highlighting how political fragmentation can undermine even economically successful administrations.

Leaders in Latin America would do well to recognize that while personal charisma and anti-establishment rhetoric can win elections, governing effectively and enduring in office require building or aligning with robust political organizations. The durability of a presidency is closely tied to parties’ ability to foster party cohesion, maintain long-term objectives, and engage constructively with both allies and opposition. However, presidents cannot expect to dramatically change these conditions. Rather, they must learn to play with the cards they are dealt.