Many of the elections taking place worldwide this year have essential implications for the global energy transition and climate goals. Venezuela’s upcoming presidential contest is one of them. Moreover, the country is losing out on significant investment opportunities given its lack of action on climate and the environment.

The vote on July 28 is about hope for a better future for the 30 million Venezuelans who have experienced a complex humanitarian crisis, unprecedented economic collapse outside of a war zone, and systemic violation of human rights. The country’s environmental record might seem trivial in the face of the Venezuelan people’s suffering. However, the repercussions of another six years of the current regime’s energy and environmental policies matter greatly for global climate goals, given the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. They also matter for the nation’s economic prospects–climate policy should be seen as a tool, not an obstacle, in the country’s recovery from an economic and humanitarian debacle.

Nicolás Maduro, who has been in office since 2013, is vying for a third term in a country with indefinite reelection. While Maduro is trailing the relatively unknown opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia by more than 20 points according to polls, he controls all relevant levers of government, including the electoral council. González Urrutia’s candidacy came after the regime banned María Corina Machado, the popular leader who won the opposition’s primary election by a landslide but was not allowed to run. Since then, Machado has campaigned incessantly for González Urrutia amid electoral harassment, the jailing of opposition politicians and campaign aides, and voter suppression tactics.

Despite the odds against political change, the inspirational defiance galvanizing the mobilization around González Urrutia is a reminder of how the election is an existential moment for Venezuelans. Almost 8 million have already fled the country, with 2 million considering migrating if the elections do not bring about change.

A sense of déjà vu would accompany a Maduro reelection, given the high risk that it would be seen as fraudulent in the face of clear voter preferences for political change. The U.S. government’s response to such a scenario will be critical, and attention will be focused on whether oil sanctions would be tightened and how they could impact Venezuela’s oil output. Venezuela is currently producing about 850,000-900,000 barrels per day (bpd) according to OPEC (compared to around 700,000 bpd in 2022) and exporting about 200,000 bpd to the U.S. Gulf Coast (compared to zero in 2021).

While analysts might disagree about how much oil sanctions will be tightened under a Democratic or Republican administration in the case of outright fraud during Venezuela’s election, most agree that if Maduro stays in office, the U.S. oil sanctions will remain. This means that Venezuela’s ability to rely on oil production and, thus, oil exports to solve its decade-long humanitarian crisis will be severely limited without political change.

However, what is less understood is how continuing Venezuela’s current environmental and climate policies would affect global climate goals and the role these policies will play in the country’s economic future, including the sizable opportunity cost without political change.

Venezuela’s climate and environmental policies

Venezuela’s environmental record becomes significantly relevant given the urgency of addressing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, global efforts to reverse biodiversity losses and deforestation, and the urgent need for developing countries to increase resilience against the physical risks of extreme weather events. During a critical decade of climate action, Venezuela has been failing dramatically on all fronts, raising economic and social risks to its citizens and the rest of the world.

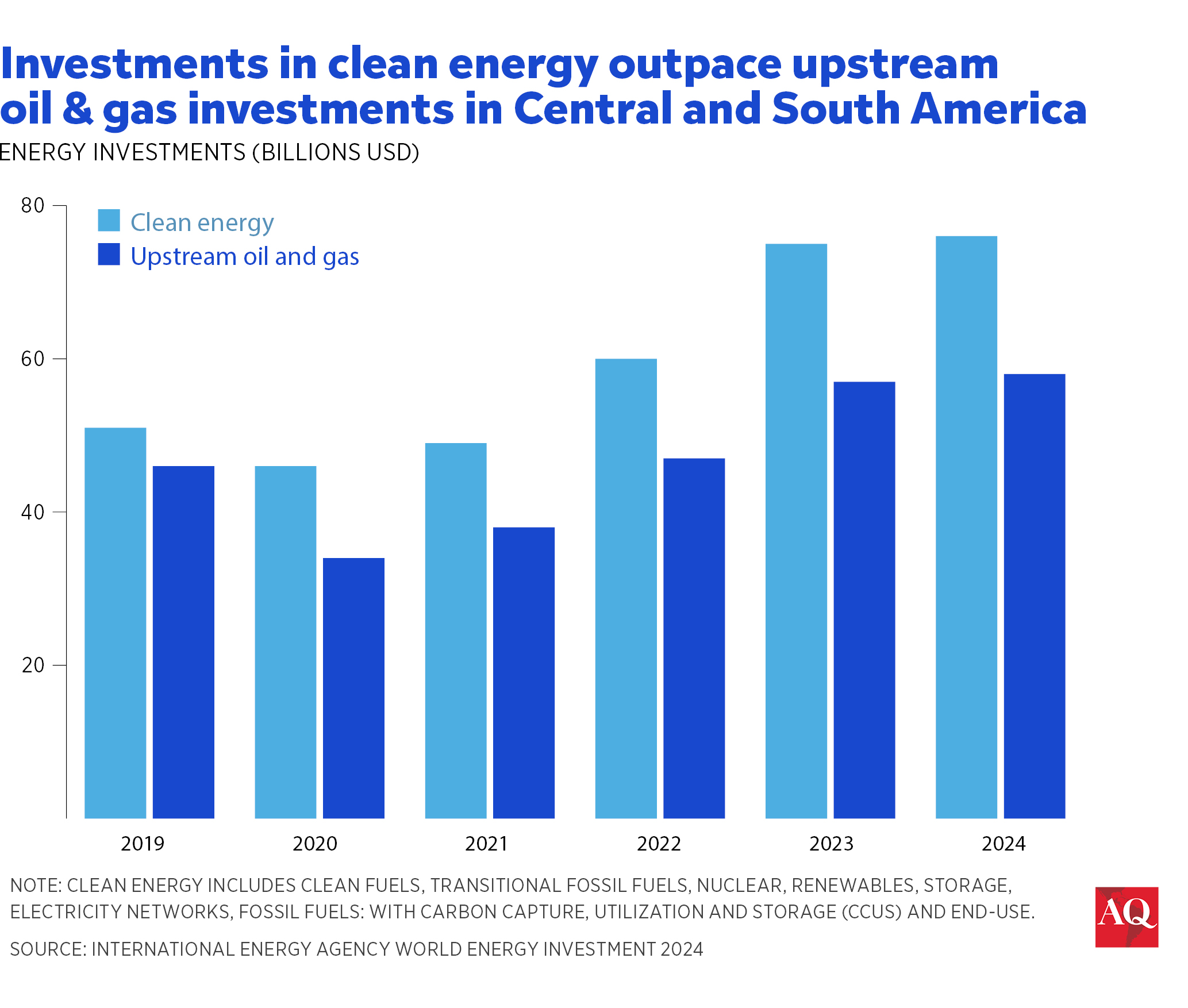

Due to the country’s lack of action on climate and the environment, Venezuela is losing out on significant financing and economic opportunities. It might benefit from a more assertive integration of environmental and climate considerations in its energy and economic policies given investment trends in the region favoring clean energy.

There are several ways in which environmental and climate considerations could bring opportunities for Venezuela. One is by unlocking financing in decarbonization projects in its oil sector. Many risks plague Venezuela’s oil industry, including sanctions, default on its financial and commercial obligations, an ailing infrastructure, expropriation history, legal constraints due to its nationalistic regulatory framework, and serious governance issues. All of this makes it difficult to attract private investments.

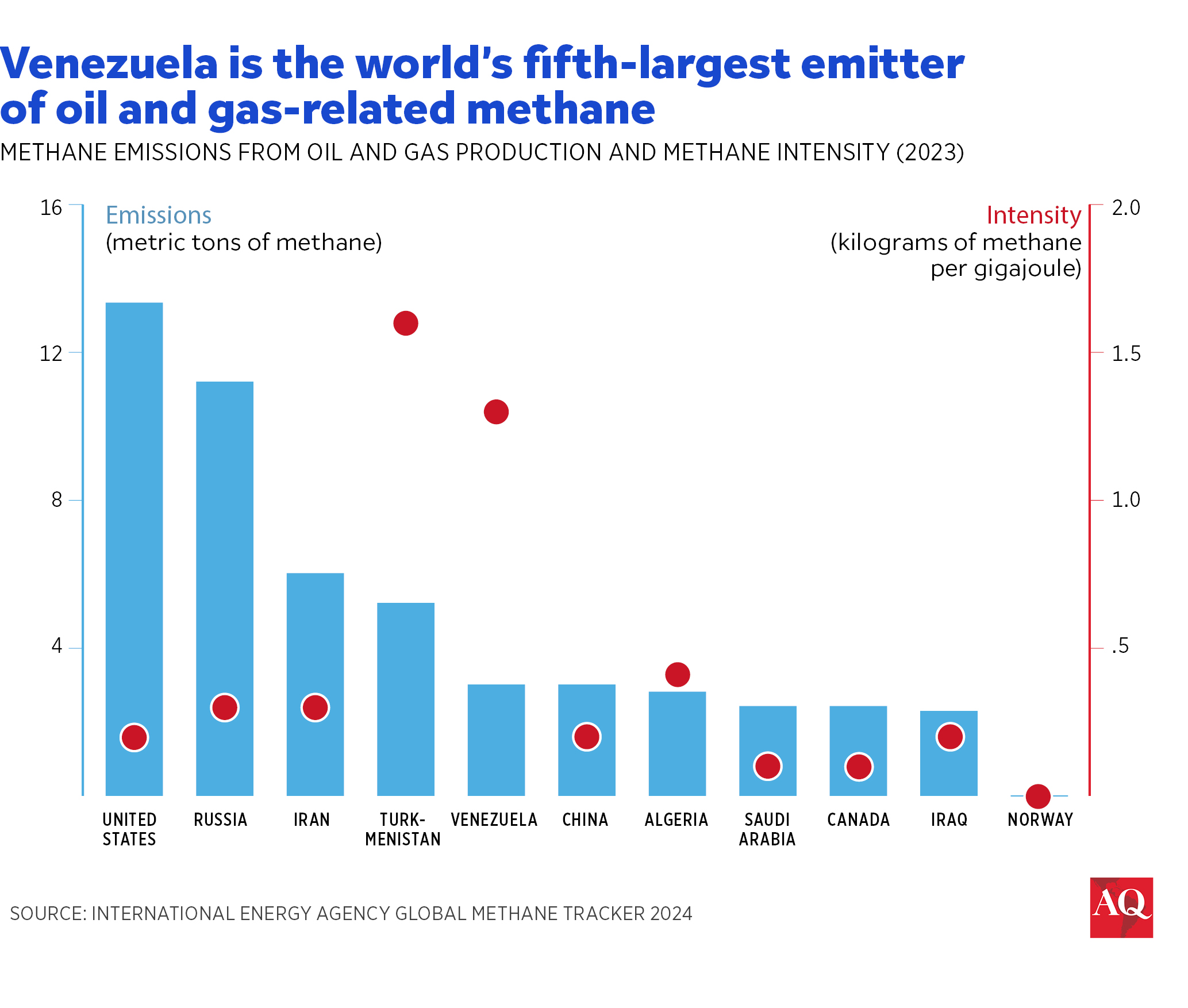

The oil sector’s record on human-caused greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions should be added to that list, given Venezuela’s lack of commitments to address its decarbonization challenges, such as venting and flaring from its oil and gas operations. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Venezuela is the world’s fifth-largest emitter of oil and gas-related methane, a greenhouse gas with more than 80 times the warming power of carbon emissions in a 20-year lifespan. Its methane emissions surpass Saudi Arabia’s, which produces more than ten times as much oil as Venezuela. According to the World Bank, Venezuela is also among the top ten countries with the largest volume of gas flaring and intensity.

The emission profile of an oil and gas asset is a relevant investment consideration when making capital allocation decisions in the industry putting Venezuela’s oil operations at a competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis many other oil producers that have committed to decarbonization practices. The international community will likely invest in a country’s decarbonization efforts if its government is willing to address this issue and ready to provide assurances of real progress. This is much more likely to occur with political change in Venezuela.

Reforestation, a second way

Deforestation is Venezuela’s second-largest source of emissions after the energy sector. The alarming pace of destruction in the country’s Amazon forest, one of the world’s critical carbon sinks, is also a source of international concern, particularly since Venezuela has refused to join Brazil’s and Colombia’s efforts to halt its deforestation. Venezuela is one of the few countries that did not sign the COP 26 declaration on forests and land use.

Such destruction can—and should—be halted and reversed to benefit the Venezuelan people and the environment. Reforestation could be one way the country could attract financing for the energy transition through carbon offset projects for the voluntary carbon market. This could provide an alternative way of life for those involved in the rampant illegal mining taking place in Venezuela’s Amazon.

Such efforts could also be incentivized through debt-for-nature swaps as part of a comprehensive debt restructuring. These swaps could not only bring fiscal relief but might also provide the opportunity for much-needed capacity building to address conservation and climate challenges within the country. However, climate finance blended instruments like debt-for-nature swaps are only likely under radically different political conditions.

As part of the Paris Climate Agreement, the Venezuelan government submitted its environmental goals, specifying that 100% of its climate efforts would only be possible with external financing. Given international commitments to mobilize financing to emerging markets and developing economies for the energy transition, adaptation to climate change, and compensation to developing countries coming from extreme weather events, Venezuela’s lack of action on climate and the environment is a huge opportunity cost that will only compound in time without political change. This is also at stake on July 28.