MEXICO CITY— Mexico is three weeks away from one of its most consequential elections in recent history. Much is at play on June 2, as the outcome of this vote is likely to have economic and political implications that will shape the nation’s future for decades. Why is there so much at stake?

From an optimistic perspective, the opportunity nearshoring brings to the country is likely to become more evident in the next six years, but only if the new administration manages to tackle the significant bottlenecks Mexico still faces in broad areas such as energy, infrastructure, security, water, human capital, and its regulatory environment. From a less upbeat vantage point, Mexico’s democracy could be at risk if the election results end up in a landslide.

Notwithstanding the result, no matter who wins the presidential race, the post-June 2 party will likely be short, as the current list of challenges—and inherent risks—the next president will face is probably the most fearsome in 25 years.

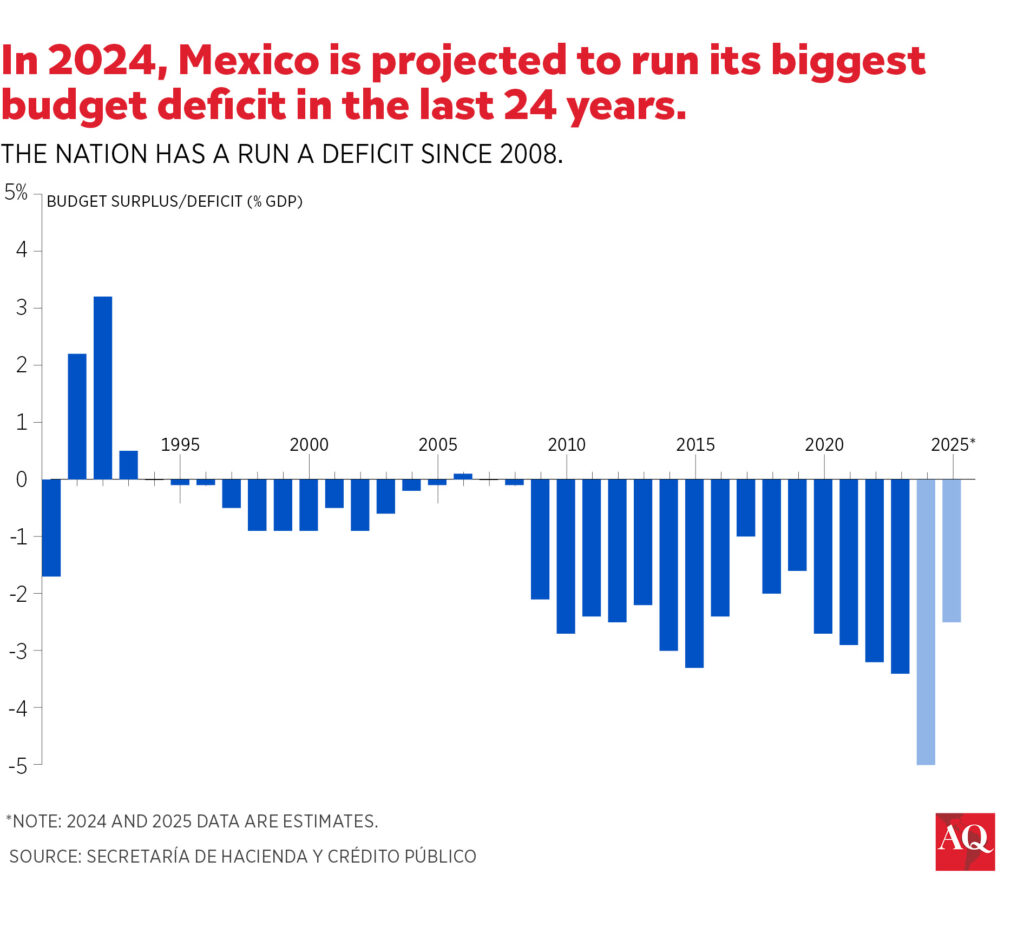

Take, for example, Mexico’s current fiscal situation. In 2018, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador was lucky enough to inherit a relatively good fiscal panorama as Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration, despite all its shortfalls, managed to advance a meaningful fiscal reform at the beginning of his administration, reduce the dependency on oil revenues, curb energy subsidies and boost the nation’s stabilization funds. As such, AMLO received a country with a fiscal deficit equivalent to only 2% of GDP, with spending needs growing but relatively under control.

In contrast, AMLO will hand off power to the next president—either Claudia Sheinbaum, the candidate of the incumbent Morena party, or opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez—with depleted stabilization funds, a modest increase in total fiscal receipts, higher energy subsidies, and substantial spending pressures coming from pensions, social programs, and higher financial costs to service the national debt. In all, a ballooning fiscal gap is nearing 6% of GDP. Moreover, general debt as a percentage of GDP will end up in 2024 slightly above 50%, almost seven percentage points higher than in 2018, a concerning level for a country that collects 17% of its GDP in taxes.

Both leading candidates have promised plenty of additional spending during their respective campaigns, rejecting in tandem the possibility of fiscal reform, at least during the first years of the new administration. At the same time, they have reiterated their commitment to maintain Mexico’s overall “responsible” fiscal framework. Both implicitly seem to admit that the overall fiscal story of the past years can be replicated in the future.

That recipe involves intensifying tax surveillance through sometimes aggressive strategies to pressure big companies to pay more taxes, as an alternative to politically costly fiscal reform, while maintaining fiscal “responsibility” through spending cuts in many (strategic) areas of the government. It has also entailed increasing social spending, particularly in the government’sold-age support program, as a means to tackle still high levels of poverty and gain political support.

Politically, this strategy has paid off for President López Obrador as he maintains high levels of support in part due to the higher levels of social handouts. Structurally speaking, however, it seems fiscally unsustainable. Without decisive action by the next president, a fiscal crisis could be a possibility in the coming years.

The case of Pemex

Or take national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos, or Pemex. Despite the administration’s effort to give Mexicans the impression that the state-owned conglomerate is moving in the right direction, it is clearly not. In 2018, AMLO inherited an indebted conglomerate with significant operational problems but with a potential transformation route through the energy reform of 2013-2014. But the scenario took a turn for the worse as soon as AMLO began his administration by effectively canceling the energy reform, closing oil rounds and farm-outs while chasing the idea of sovereignty in the production of refined products.

Almost six years later, Pemex’s production continues to fall to a more than four-decade low. The company still loses money refining oil (900,000 million pesos in the past five years) and owes $22 billion to its suppliers. Perhaps more worrisome is that while its overall debt has not risen from the whopping $102 billion burden, its short-term obligations have tripled, while needing as much as 1.6 billion pesos of financial support from the federal government to stay afloat. And even with the government studying steps to absorb as much as $40 billion from Pemex’s books, the company’s path is unsustainable.

Security issue

Plenty more challenges and risks are likely to get in the way of the next president. Besides a failed energy policy, there are significant bottlenecks in infrastructure, setbacks in education and health, a fall in productivity, and a low economic growth potential. But security is probably the most urgent topic. The six-year term of López Obrador will end up close to 200,000 homicides, according to official figures, double the total of the Felipe Calderón administration (2006-2012) and 30% higher than the Peña administration (2012-2018).

Despite mild improvement in some other criminal activities, the next president will inherit a very violent landscape, with some parts of the national territory effectively captured by brazen criminal organizations, a criminal landscape that is limiting Mexico’s growth potential and a security budget far below what is needed (Mexico spends little more than 1% of GDP on public order and security).

In sum, very soon, in order to tackle the adverse legacies of the current administration, the next president of Mexico will have to make uncomfortable political decisions that will likely shape the six-year administration. One thing is for sure: seeking to maintain the current status quo will lead to a failed presidency.