This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s ports

“Why would I want to keep on living in a country where people hate me?” So says Augusto Pinochet, who, after two centuries of life as a vampire, has finally decided to die. The Oscar-nominated film El Conde, directed by Pablo Larraín, bitterly satirizes Chile’s infamous dictator, who staged a coup against democratically elected President Salvador Allende, and then ruled the country for 17 years.

In this grisly farce, up for an award for its cinematography on March 10, Larraín manages to inject freshness and humor into a story that has been told and retold for decades. But despite its clever appropriation of the horror genre, El Conde does little more than retell the same old joke: Pinochet, reimagined as an actual bloodsucker, denies any wrongdoing or blood on his hands. In the process, Larraín seems to overlook the perspective of real Chileans of carne y hueso, both on screen and off.

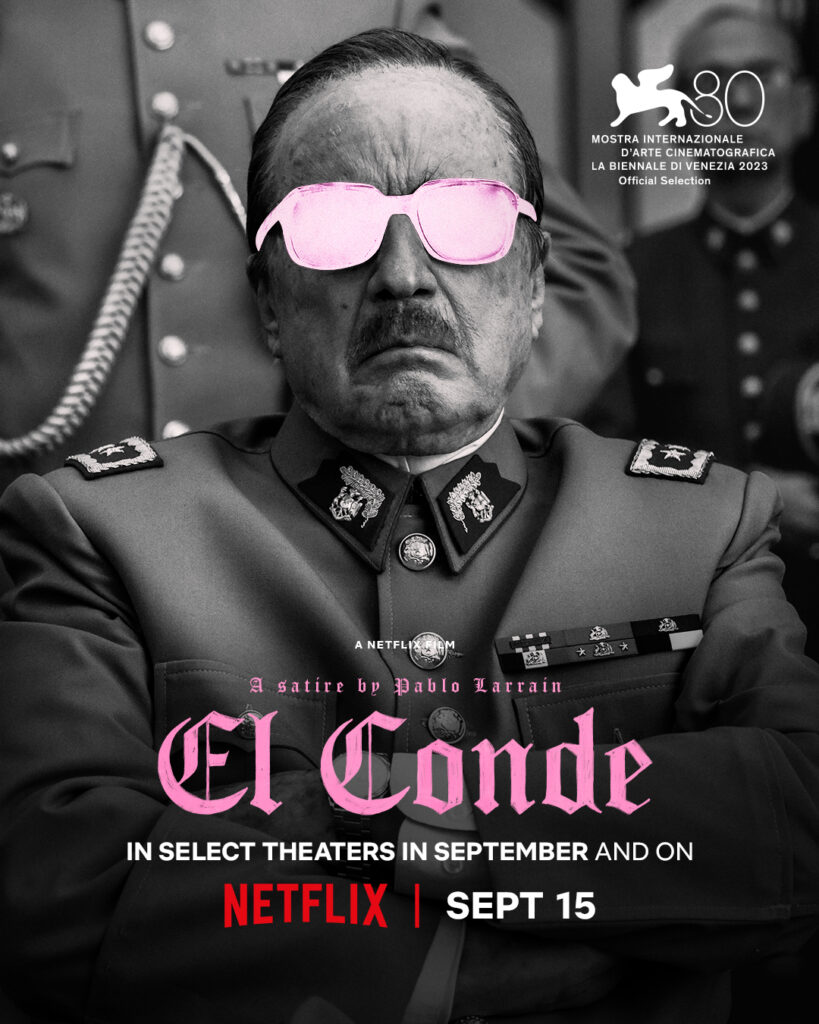

El Conde

Directed by Pablo Larraín

Screenplay by Pablo Larraín and Guillermo Calderón

Distributed by Netflix

Starring Jaime Vadell, Gloria Münchmeyer, Alfredo Castro and Paula Luchsinger

Chile

Alone with his wife Lucía (a human) and butler Fyodor (a vampire, like his employer), Pinochet spends his old age on an isolated ranch. His five adult children eventually arrive, eager to claim their chunk of the family fortune. Their father’s wealth is hidden across dozens of offshore bank accounts and real-estate properties, an arrangement that calls for the help of Carmen, an accountant, who also happens to be a nun. Unforeseen problems arise when Pinochet falls for this young woman—and many human hearts are blended into smoothies for their nutritious blood along the way.

On a deeper level, El Conde spins a yarn that extends far beyond Chile. Pinochet was once Claude Pinoche, a French orphan who grew up under the 18th-century ancien régime. As a young officer in the royal army, he witnesses Marie Antoinette’s execution by guillotine, tastes the droplets of blood left on the blade that severed her head, and resolves to “use his powers to fight against all revolutions, an eternal subject to his beheaded king.”

Pinoche resurfaces during revolutions in Haiti, Russia and Algeria—always backing the losing side—before he settles on an “insignificant corner of South America,” where he changes his name definitively. The narrator telling us this, we soon learn, is none other than Margaret Thatcher, another vampire and, quite unexpectedly, Pinochet’s biological mother.

In no uncertain terms, Larraín situates Pinochet’s despotic rule in a historical lineage of right-wing politics. By making supporters of the monarchy in the wake of the French Revolution into relatives of the Iron Lady in 1980s Britain, El Conde risks collapsing history into a Manichean dichotomy, putting left and right in a boxing ring. But this contest lacks an audience: Ordinary Chileans are virtually absent from Larraín’s narrative.

Perhaps this omission gestures at the thousands who were killed or disappeared during Pinochet’s regime. But in interviews, Larraín seems most interested in the “overwhelming,” “eternal” figure of Pinochet. As one critic put it, “Who needs a movie that is almost all predators, with barely a word from their prey?”

Meanwhile, the real Pinochet’s legacy continues to loom over Chilean society. The 1980 constitution he oversaw remains in place. It has been repeatedly amended, but efforts to replace it have failed, twice. According to a 2023 poll, more than a third of Chileans believe Pinochet saved their country from Marxism and 36% believe the military was right to carry out the 1973 coup.

In El Conde, Chile’s polarizing dictator fakes his 2006 death and lives on for many years afterward. But Larraín hardly needs to recruit the supernatural to tell this story. Vampires are not needed for the dead to keep on living.