Read more about China and Latin America in the Winter 2012 issue of Americas Quarterly to be released on January 26, 2012.

Brazil and China’s economic relations have grown at a rapid clip in the last five years. But their new ties are also leading to increased wariness by the Brazilians.

The real challenge comes in the areas of trade and investment. Brazil is concerned about the skewed nature of their trade, with China importing natural resources and Brazil importing higher value Chinese products. The concern also extends to foreign direct investment on both sides. The Chinese have ratcheted up their stake in local Brazilian industry while Brazilian companies struggle to gain entry into the Chinese market.

Macroeconomic Policy Inconsistencies Compared

Within generally well managed macroeconomic frameworks, both China and Brazil have implemented similarly inconsistent macroeconomic policies in part in response to economic challenges and the global economic downturn.

The similarities are not a coincidence. China’s developmentalist, state-centric model of economic growth first captivated and became a model for Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s administration (2003–2010) as they continue to for the current President Dilma Rousseff. Ironically, while this developmentalist romanticism still holds sway in Brasilia, in Beijing China’s traditional dirigiste policies are falling out of favor as reformers call for a move away from state intervention to greater reliance on market forces.

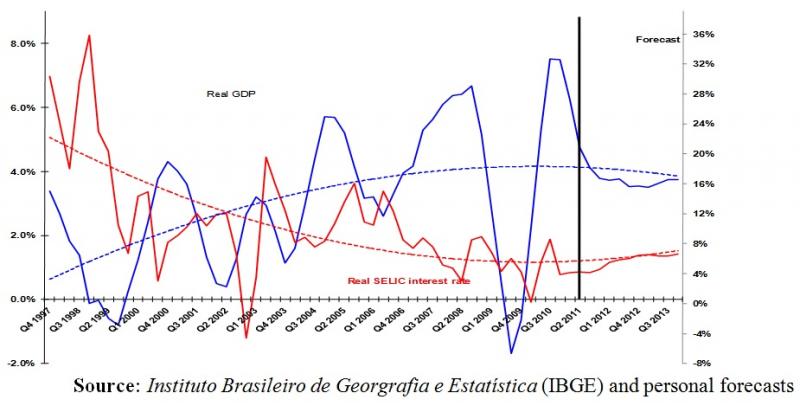

Brazil’s reform efforts over the late 30 years included a partial opening of the economy, privatizing inefficiently run state-owned enterprises (SOEs), adjusting fiscal accounts, and adopting a monetary regime that explicitly works to keep inflation at acceptable levels–undoing part of the developmentalist model of the 1960s and 1970s. The reforms generated long-term real GDP growth and contained currency volatility—the exception being the brief economic downturn during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis [See Figure 1].

figure 1. brazil: real GDP growth and real interest rates

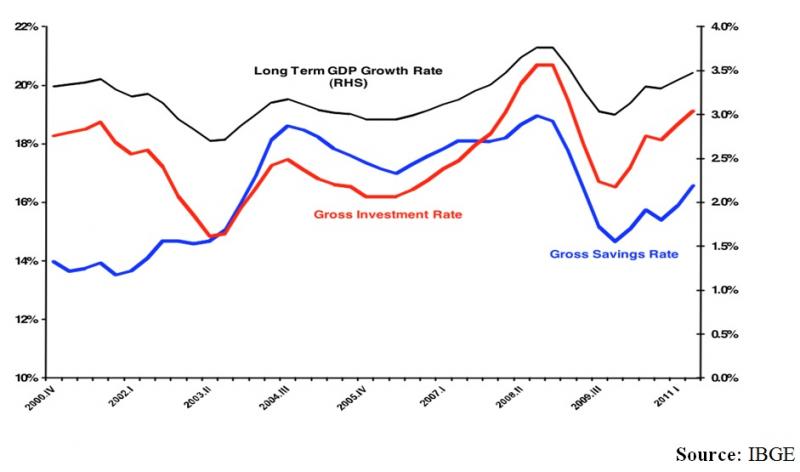

As a result of these trends and the level of predictability and credibility Brazil’s macroeconomy has achieved, analysts have raised Brazil’s long-term sustainable growth rate to above 4 percent. But for all the optimism, Brazil’s investment GDP ratio has still shown no signs of exceeding 20 percent, nor has the savings rate shown any trend to reach similar levels (See Figure 2). The figure shows that the current investment ratio is at 18.5 percent and the savings rate is at 16 percent. Our own estimate of Brazil’s long-term growth rate comes to just 4 percent. In other words, despite huge advances, Brazil’s reform effort is unfinished.

figure 2. brazil: savings and investment (percent of gdp) and long-run growth rate

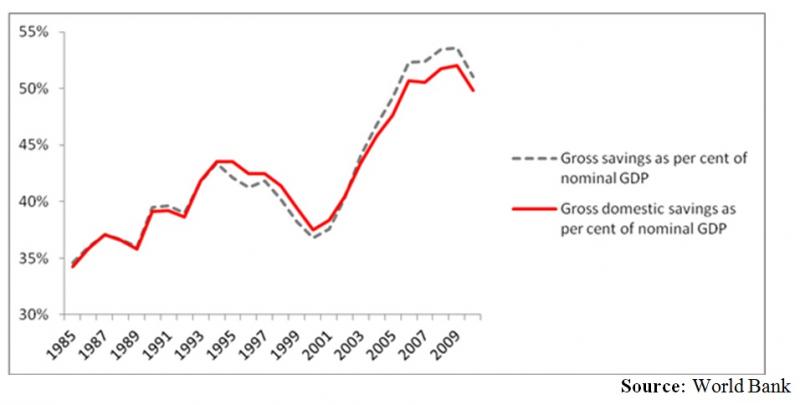

In sharp contrast, China’s savings rate and long-term growth rate are much higher than Brazil’s, though the transition to lower savings rates and more moderate growth are already underway. And unlike Brazil, China is facing a demographic challenge given a rapid aging of its population that will lead to soaring dependency ratios after 2015 (See Figure 3).

figure 3. china: gross savings (percent of gdp)

Even if long-term economic trends diverge, though, Brazil and China’s macroeconomic policy responses to the economic downturn four years ago have followed remarkably convergent paths. At the height of the 2008–2009 financial crisis (fourth quarter, 2009), the Lula administration chose to expand official credit through the Brazilian National Economic and Social Development Bank (BNDES), the Caixa Econômica Federal (Federal Thrift Institution), and the Banco do Brasil. This action emulated the stimulus plan put into place by the Chinese government which was primarily implemented through expansionary credit policy.

Ironically, for Brazil the reaction to the crisis was in many ways a throwback to Brazilian development policies of the 1970s that the reforms of the last 20 years sought to undo. The reason was many failed. The Brazilian government’s policies to expand credit in the late 1960s and 1970s ran into serious insolvency problems, especially in the housing market.

The recent Chinese credit expansion, much larger and implemented earlier than the current Brazilian one, has already run into an increase in nonperforming loans (NPLs). And Brazil is now beginning to show an increase in NPLs, in part because private banks have refused to loosen lending. However, the current slowdown could cause the balance sheets of official banks to deteriorate.

In monetary policy, Brazil moved to targeting inflation through changes in an overnight interest rate: the SELIC. The current financial upheaval in the United States and Europe, worries about excess financial leverage and the strength of the real have resuscitated the idea of limiting inflation through controlling credit—mainly through increases in required reserve and capital ratios, now referred to as macroprudential policies. Brazil has implemented a series of these increases, mostly for private banks. Public sector banks have either been exempt or can get around them via increases in bank capital funded by the Treasury. In China, monetary authorities already rely mostly on direct controls on bank lending to implement monetary policy rather than interest rates. But this effort to control bank lending has proved difficult to implement in practice; banks have found numerous ways to evade such controls.

The problem in this case is the governments are using one policy tool for two goals. It is one thing to protect the banking system by preventing overleveraging; it is another to substitute the policies of tighter credit for changes in the policy rate to fight inflation. Perhaps using macroprudential policies may avoid some currency appreciation that comes with higher interest rates, but it also suffers the lack of inflation dampening that comes with higher rates.

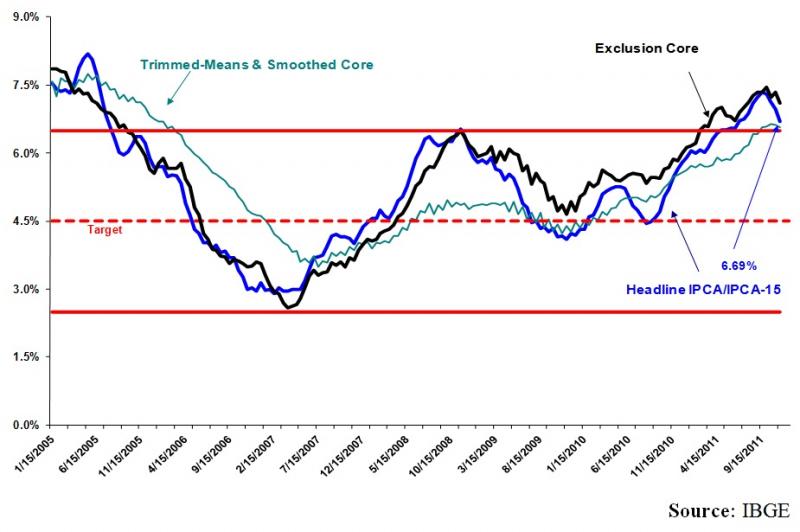

The official IPCA inflation rate has not only exceeded the 4.5 percent target for some time now but has broken through the top of the tolerance band (See Figure 4). Inflation is only now creeping back toward the 6.5 percent top of the targeting band. Moreover, the Banco Central has strangely started to cut rates to try to preempt any negative effects from the recent worsening of the international situation on economic growth. This experiment is unlikely to work, and the Banco Central likely will have to return to more traditional inflation targeting to bring inflation back to 4.5 percent, the midpoint of the targeting band.

figure 4. brazil: ipca inflation still high

China’s monetary authorities have also signaled an end to their tightening cycle. In November 2011, a decision was taken to cut banks’ reserve requirements in response to signs that inflation had begun falling. But as in Brazil, the current ebbing of inflationary pressures could prove short lived and be reversed again in six months’ time with a rise in food prices. Both countries can point to short-term successes in limiting inflation but the longer term outlook points to a resurgence of inflationary pressures due to the absence of effective monetary controls.

Trade and Investment Ties

The pattern of external trade and investments already has generated conflict between the two rising economic powers, conflicts that are likely to grow in the years ahead. Brazil’s asymmetric trade and investment relationship with China has been the main point of friction, and doesn’t look likely to go away any time soon.

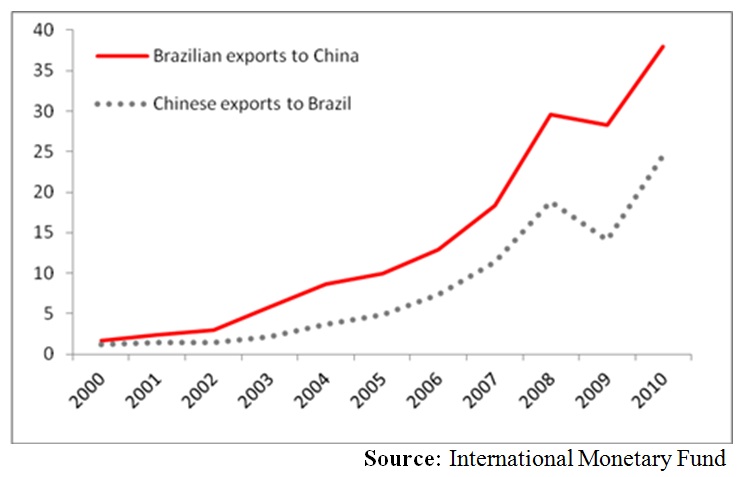

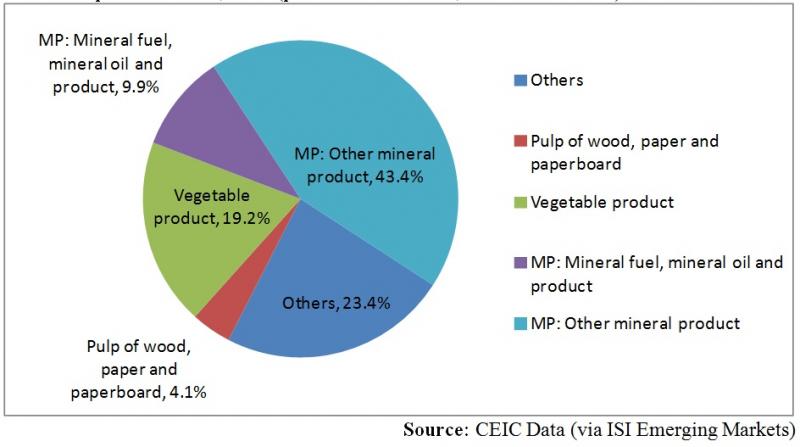

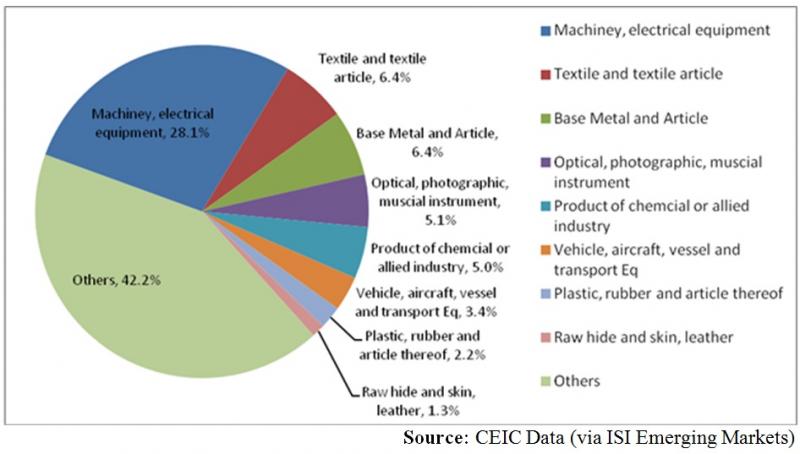

As the early Brazil–China trade relationship has grown (See Figure 5), so has the imbalance in the terms of trade (See Figure 6). Brazil’s exports to China have concentrated on commodity and semi-processed, commodity-based exports, including iron ore, vegetable products, crude oil, and pulp and paper. The structure of Brazil’s imports from China (See Figure 7), however, is far different. Brazil mainly imports high value-added goods such as machinery and electrical equipment, chemical products, base metals and textiles. This trade relationship turns on its head the Brazilian developmentalist dream of exporting high value-added and diversifying away from commodity production.

figure 5. brazil-china bilateral trade, 2000-2010 (us$ billion)

figure 6. Brazil’s exports to china, 2010 (percent distribution, HS classification)

figure 7. Brazil’s imports from China, 2010 (percent distribution, HS classification)

This pattern of growing trade has spurred protectionist reactions in Brazil to the potential knock-on effects: deindustrialization and continued strengthening of the real. China is often the target of protectionist sentiments in the manufacturing sector and Brazil’s fear of falling victim to the so-called “Dutch Disease” (exporting raw materials and importing manufactured goods). Many Brazilian industrialists have criticize the “invasion” of Chinese products and blame imports for the fall in Brazil’s industrial output, demanding “emergency action.”

The Rousseff administration has moved to protect local industry, including stricter anti-dumping regulations and tax breaks. This will also likely extend to the oil and gas industry as well. Depending on the estimated risk of the development of a given block, the National Petroleum Agency (ANP) sets minimum domestic content requirements between 39 percent and 77 percent. The government is likely to expand these local content requirements in future exploration and production (E&P) bidding rounds, further strengthening local industry. Local content requirements and granting of preferential terms for locally produced goods also is likely to be extended into other industries, especially capital-intensive infrastructure projects.

China is looking to Brazil not only as a source for natural resources but also as reliable market for value-added goods and technology, specifically in the infrastructure sector. In 2009, China North Rolling Stock won a $143 million (renminbi 1 billion) order for 20 trains for Rio de Janeiro’s metro railway system. Chinese companies will certainly bid for much bigger contracts in 2012 for the Campinas-São Paulo-Rio de Janeiro high-speed train link.

Chinese manufacturers’ strategy to set up operations in Brazil highlights their drive to build local factories to supply Brazilian consumers with low-cost products and to export these products from Brazil to the rest of Latin America. In part, this reflects China’s increased political focus on the region, but it also stems from Beijing’s awareness of the need to diversify its export markets. While the new Five-Year Plan (2011–2015) aims to rebalance the economy by boosting domestic demand, exports remain an important driver and China wants to explore new destinations for its products.

In September 2011, in response to growing concerns Brazil implemented countervailing duties on a number of Chinese products, and with Asian exporters in mind, increased the Industrial Production Tax (IPI) on luxury auto imports by 30 percentage points. Brazil has also joined the United States and others in accusing China of manipulating its foreign exchange rate to keep it undervalued.

China’s interest in Brazil has centered on Brazil’s ability to meet growing Chinese demand for raw materials and foodstuffs. At the beginning of the relationship—dating to the middle of then-President Lula’s first term economic term—ties were characterized by talk of large-scale Chinese investment projects in Brazil but little action on the ground to implement them.

China’s push now to expand the relationship from trade to foreign direct investment has added another dimension to the tensions with Brazil. Beijing’s leadership has shown a keen interest in developing a broad relationship with Latin America both for economic reasons and as a way of building political partners, bilaterally and in the G20.

An example of the central government’s “Going Out” strategy is the State Grid Corporation of China’s (SGCC) purchase of seven Brazilian electric transmission companies. SGCC’s longer term target is to develop ultra-high voltage (UHV) transmission technology, which is particularly suitable for countries with geographically uneven resources and demand, like China and Brazil. UHV lines could triple the transmission distance compared to the 500 kV lines currently used in Brazil because they reduce electricity loss by up to 25 percent.

On the Brazilian side, the government has welcomed Chinese minority equity investment. In the authorities’ eyes, minority investment confirms the attractiveness of Brazil as an investment destination without creating political concerns about foreign ownership of Brazilian resources. Chinese investments in the natural resource sector include:

• A 40 percent stake in Repsol Brasil by Sinopec for $4.2 billion (renminbi 7.1 billion), under an agreement announced in October 2010.

• Sinochem’s acquisition of a 40 percent stake in the Peregrino field from Norway’s Statoil for $3.07 billion with estimated recoverable reserves of 500 million barrels.

• Wuhan Iron & Steel’s (WISCO) 2009 acquisition of a 21.5 percent stake in MMX, Eike Batista’s iron ore mining company, for $400 million.

• Sinopec signed an agreement with Petrobrás in April 2010 that includes the possible sale of stakes in two exploration blocks in the Para-Maranhão Basin as well as cooperation in E&P and refining. And Sinopec is considering possible partnerships in the Rio de Janeiro Petrochemicals Complex, to which Petrobrás has had trouble attracting private investors.

• Sinopec and CNOOC have expressed interest in a stake in OGX Petroleo & Gas. The deal could be worth as much as $7 billion.

Aside from the obvious advantage of allowing Chinese companies to sell in Brazil under local content rules, investments in local assembly plants create jobs, mitigating some of the political pressure from Brazilian companies. For example, several states courted automaker Chery to set up shop before the Chinese firm opted for São Paulo. Chery’s $130 million project for a car plant in Jacarei (São Paulo) is to be completed in 2013.

Although China’s acquisition of minority stakes in Brazilian companies have been welcomed (as has Chery’s investment), acquisitions of majority stakes in Brazilian natural resource companies have aroused concern. Brazilian Ambassador to China Clodoaldo Hugueney expressed his misgivings about Chinese investments in Brazilian natural resource companies in an interview with the daily O Estado de São Paulo in October 2010. He said that acquisition of mining assets in Brazil by Chinese investors could raise conflicts of interest, and added that Brazil does not need foreign capital to expand its agricultural sector. One Chinese deal last year—East China Mineral Exploration and Development Bureau’s $1.2 billion acquisition of Brazilian iron ore producer Itaminas Comercio de Minerios—was criticized by steel manufacturers. Itaminas has iron ore reserves of roughly 1.3 billion tons.

Some Chinese investors also have expressed their concerns about Brazil’s model for infrastructure projects. In September 2011, Chang Yunbo, the vice-general manager of the overseas investment division of the China Communications Construction Company said that Brazilian projects need to be properly structured to receive investments and did not expect any Chinese company to invest in projects that would not be profitable. Chinese firms will not take on risk that local government needs to shoulder.

For Brazilians, reciprocal manufacturing investment continues to lag in China.

Brazilian trade missions have explored opportunities for expanding manufacturing investment in China with meager results so far. The outlook is for much heavier investment flows from China to Brazil than in the other direction. Brazil’s highest-profile sales have been of 77 Embraer aircraft to Chinese airlines. Embraer forecasts that Chinese airlines will expand their fleets by an additional 950 regional jets in the next 20 years. But Chinese authorities are insisting on increased technology transfer from foreign suppliers as they build up the domestic industry to meet this demand—a demand that makes Embraer wary.

But Embraer’s experience with production in China has proven frustrating. Embraer planned to end production of the 50-seat ERJ-145 jet at its plant in Harbin at the end of 2011 because local sales have lagged. Embraer would like to switch production to the larger ERJ-190 but has not yet received Chinese government authorization as it would compete with China’s own ARJ21 jet (70-110 passenger capacity).

Will Coming Disappointments Change Policy?

These two policy tacks may entail a change by both the Brazilian and Chinese authorities. On the macroeconomic front, the Dilma administration has reacted to the challenges of higher inflation, an appreciating exchange rate, slower world growth, higher inflation, and Brazil’s increasingly lagging competitiveness.

The government has already moved to make fiscal policy the workhorse of inflation stabilization much like the Asian model (including China) where governments keep to strict fiscal policy. The challenge, however, is that the degree of fiscal adjustment so far is smaller than is needed to significantly weaken the real exchange rate.

To address the fundamentals of the Brazil’s economic problems, though, the government needs to return to an agenda of privatization, regulation or deregulation of sectors that the government does not manage well, e.g. roads, ports, etc. With the massive investment demands of the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics and the huge demands to improve the ports, railroads and roads, a better environment for foreign investment will prove crucial to the fruition of these projects. The recent decision to privatize a number of airports starting in August 2011 is a good sign.

Macroeconomic concerns are affecting trade and investment policy as well. The alleged undervaluation of the renminbi and the strong real has led the Brazilian government to impose antidumping actions on China. Although Dilma’s predecessor, Lula, resisted erecting new trade barriers, her administration has pursued counterproductive protectionism. The renewal of trade liberalizing efforts, especially in capital goods, would prove a good start in weakening to currency and improving efficiency. By following another Chinese example, the government should complement these moves with increasing the convertibility of the real through dismantling capital controls.

None of these are easy steps, politically or economically. Nor are they a panacea. As with any trade relationship among emerging economies, there will always be elements of competition and conflict. For all the talk of “win-win” by the Chinese and boasting by the Brazilians of their Chinese-fueled economic growth, both economies are increasingly locked in a struggle to defend national—and developmental—goals.

(Homepage photo courtesy of Flickr user ‘thewamphyri’)