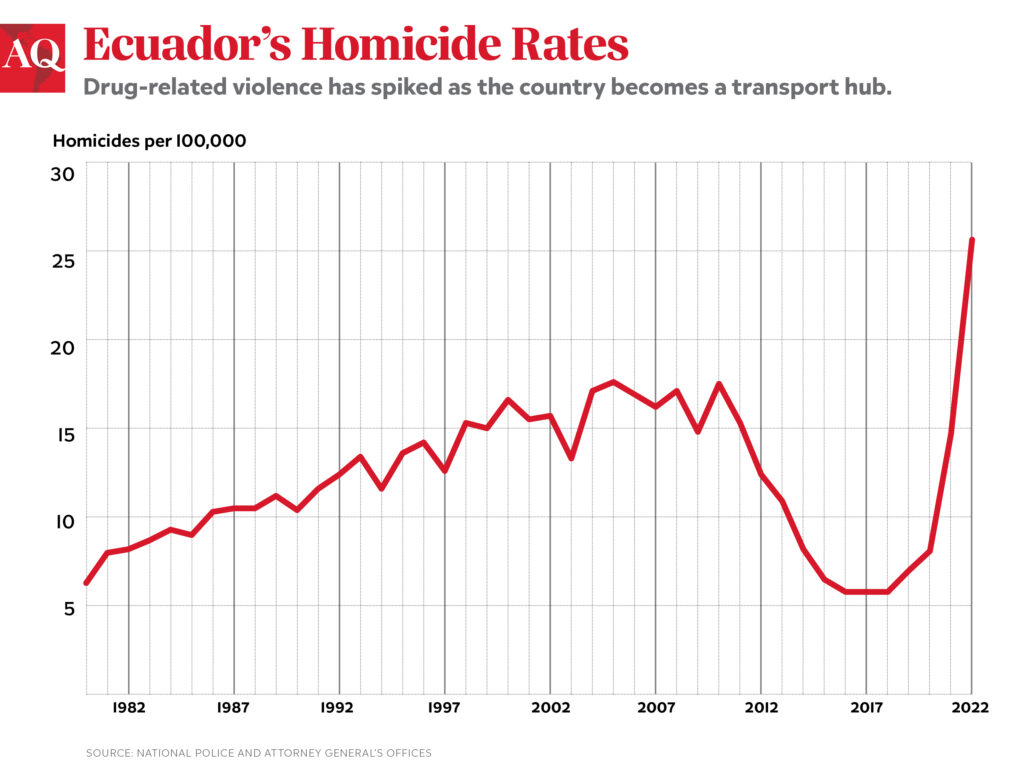

GUAYAQUIL, Ecuador — Even in a region known for record-setting violence, Ecuador’s recent spiral into lawlessness and bloodshed stands out. Deadly crime in the Andean nation has now hit historic highs, with a national homicide rate surpassing that of Brazil and Mexico, long ranked among Latin America’s most murderous countries. Little wonder President Guillermo Lasso’s approval ratings have tanked, fueling calls for his impeachment–sparked by corruption allegations linking the president’s brother-in-law to drug traffickers. (Lasso and his brother-in-law have denied the accusations.)

At the center of Ecuador’s troubles is the bottomless global demand for cocaine. Thanks in part to Balkan gangs, Ecuador now serves as both a center for transshipment and export of cocaine from Colombia and Peru. The crisis is acute in Esmeraldas, on the Colombian border, and especially in the port city of Guayaquil, the country’s gateway to the world.

Home to five of the nation’s eight shipping terminals, Ecuador’s richest city is also one of the world’s 25 most dangerous. Guayaquil last year notched some 47.7 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, up seven-fold in five years. The mayhem persists, despite seven states of emergency declared since mid 2021. Last week, President Lasso authorized civilian gun use “for personal defense,” a move that smacks more of despair than of command and control.

Once lauded for its strategy to contain lethal drug gangs, Ecuador today looks to be firmly in their grip. The spike in violence tracks closely with a sharp increase in deadly disputes between organized groups vying for advantage in Ecuador’s surging cocaine trade, with repercussions well beyond this nation of 18 million people. Driving the deadly drug trade are emerging clusters of criminal networks, with global reach and ambitions. Reining in the violence will take nothing less; only a renewed commitment among local, national and regional authorities to foster interagency collaboration, cross-border cooperation, data-driven policies and intelligence can prevent Ecuador’s security crisis from becoming a regional emergency.

European Connection

Albanian organized crime started migrating to Ecuador in the 1990s, lured by the prospect of joining forces with thriving local cartels and relatively lax border controls. Until recently, Albanians could freely enter Ecuador without a visa. That laissez faire turnstile policy ended when Ecuador imposed tighter visa requirements in 2020.

Roughly 33% of the cocaine seized in Ecuador in 2021 was destined for European markets, compared to just 9% in 2019. Notably, the Balkans are a key new hub in this lucrative intercontinental trade (worth $10 billion in 2017), with Albanian gangs playing an increasingly prominent role on both sides of the equator.

Following record busts in 2021, despite the pandemic lockdowns, Ecuador currently ranks third for cocaine interdictions (6.5% of global seizures),surpassed only by Colombia (41%), where the coca crop is booming, and the U.S. (11%).

Guayaquil accounts for roughly 96 of the 210 tons of cocaine Ecuador seized in 2021. Most of the cocaine is concealed in shipping containers—only around 8% to 10% of which are subject to inspections.

With counter-narcotics operations squeezing Brazil, Colombia and Peru, Ecuador has become something of a sweet spot for foreign traffickers. Dollarization and corruption facilitate the purchase of fraudulent documents such as personal identification, passports and export licenses. Most of the known Albanian crime operators reside in Guayaquil, often under false identities.

Balkan news media spared no details on how Albanian, Colombian, Mexican, and even Russian cartels do battle for control of Guayaquil. At least six Albanians were executed gangland style in the last decade. Some Ecuadorian intelligence sources suggest that Albanians recruit dominant local gangs as “favorite partners,” while other sources say the Albanians aim ultimately to control the entire supply chain.

The Albanian mafia resorts to a multitude of ruses to traffic drugs, from using front companies to abscond cocaine in banana, tea and shrimp shipments to cloning customs seals to disguise breached containers. Little of this would be possible without a wink and a nod from officials on the take.

Ecuadorian intelligence has long kept the Albanian mafia under watch. In the 2014 “Operation Balkans,” they found that two alpha crime syndicates – the Azemi and Rexhepi gangs – infiltrated port operations to acquire packing lists and hand-pick containers bound for Europe. Albanians detained in the operation were also identified as the scheme’s financiers and custodians.

Operation Balkans ended with the arrest of ring leader Remzi Azemi and 11 other gang members, including Albanian and Ecuadorian nationals. Ecuadorian police and prosecutors accused the organization of stockpiling cocaine in Guayaquil bound for Europe. Azemi escaped custody a month later, resurfaced in Europe in 2017, and was later arrested in Germany.

Azemi still faces criminal charges in Ecuador, including for the murder of his Ecuadorian spouse and the Albanian-Montenegrin fugitive Fadil Kacanic.

Ecuadoran authorities have yet to divulge their findings in the case or even to acknowledge the presence of foreign nationals with links to the brutal Balkan mafia. Two different intelligence sources consulted went so far as to suggest “high-level” collusion between the Ecuadorian police and the Albanian mafia, one of whose gang members reportedly died at the hands of the police. While those reports remain unconfirmed, they leave little doubt about the dire turn for law, order and public safety in Ecuador –and beyond.

—

*Muggah and Margolis contributed from Rio de Janeiro

Andrade is a senior adviser to the Igarapé Institute, a Brazil based think tank, where Muggah serves as innovation director and Margolis as an editor and adviser.