This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Uruguay

As he would later tell the story, Arthur Bispo do Rosario was 27 years old when he had his first vision. It was in the backyard of the house where he lived in Rio de Janeiro, three days before Christmas in 1938, that seven angels came to him.

Bispo left the house and wandered the city streets for two days before making his way to a monastery, where he introduced himself as “the one who had come to judge the living and the dead.” The friars called the police, and Bispo was soon diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Before then, he’d spent time in the Brazilian navy, as a competitive boxer, and finally as a handyman after he injured his foot.

Now, he was never to fully live outside a mental institution again. But the outside world lived on within him. In the asylum where he spent half a century, going in and out at different times of his life, the voices in his head delivered Bispo his life’s mission: to create representations of everything under the sun, so that he could present them to God on Judgment Day. Like a version of Noah’s ark, he set out to forge a sample of all the world had to offer—from everyday objects like shoes and mugs, to abstract concepts like nations and ideas. This inventory took the form of sculpture and embroidery.

Bispo do Rosario: All Existing Materials on Earth

Curated by Aimé Iglesias Lukin, Ricardo Resende and Javier Téllez with Tie Jojima

January 24–May 20, 2023

Americas Society

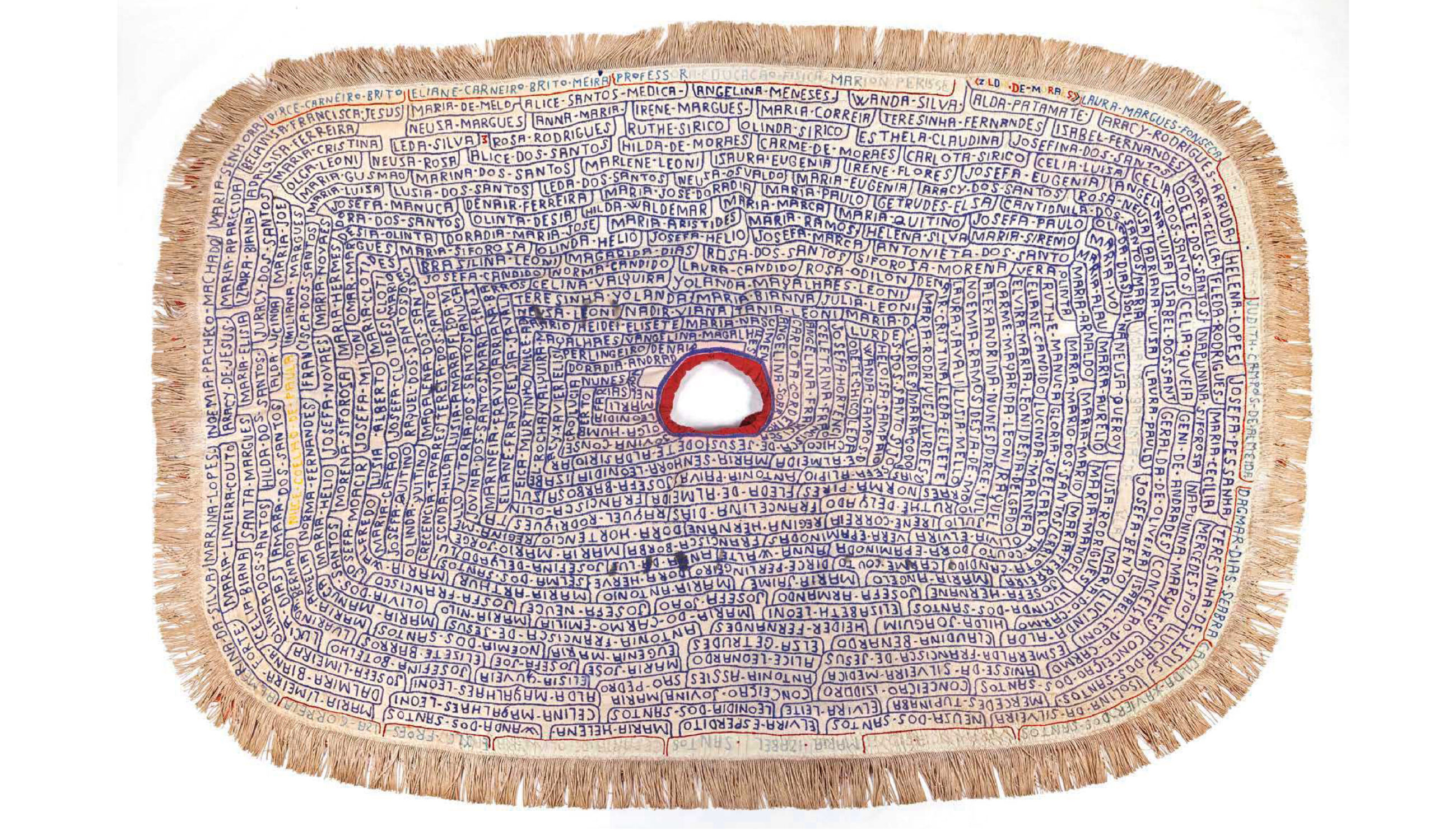

A selection of the some 1,000 works that Bispo created over the course of his life is on display at the Americas Society gallery starting this January, the first exhibition of its size and scope ever organized outside Brazil. It will include what is perhaps Bispo’s most important work, the Manto da apresentação (Annunciation garment), a mantle he intended to wear on Judgment Day. Designed to be worn like a poncho, over the head, it is embroidered on the outside with everyday objects and abstract figures and on the inside with the names of everyone he had met—nurses, doctors, fellow patients, friends.

It isn’t known where Bispo learned his craft. Perhaps he took hints from his native Sergipe state, where there is a tradition of female embroiderers— or maybe he picked it up during his time in the navy.

What is clear is that this exhibition shows the breadth of Bispo’s ability and vision. There are the jackets embroidered with the story of his 1938 vision. There are the estandartes, banners studded with everything from maps of his asylum, to representations of the human body, to names of countries. And there are sculptures of everyday objects that he enveloped in the same threads he used to sew garments and banners.

The exhibit also makes clear the richness and complexity of Bispo’s spiritual experience, characteristic of Brazilian religious culture. While he creates his work for what is understood to be a Christian God, his pieces also reflect Afro-Brazilian religious beliefs— featuring, for example, a messenger deity called Exu capable of traveling between worlds.

One thing we do know is that Bispo did not see himself as an artist. He viewed his pieces as work he was ordered to do by voices he heard, and he did not like to be away from them. Only once in his life did he allow parts of his oeuvre to leave the asylum for an exhibition.

But despite this reluctance, it is as an artist that he lives on in Brazilian culture, posing questions still discussed today about artistic creation and expression—about what counts as art, where art comes from and where it belongs.