This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on millennials in politics

Owning a pool sounds fun, but few middle-class families manage to enjoy this luxury. The reasons are clear enough: They require high up-front and maintenance costs, not to mention ample yard space. In temperate climates they aren’t even useful year-round.

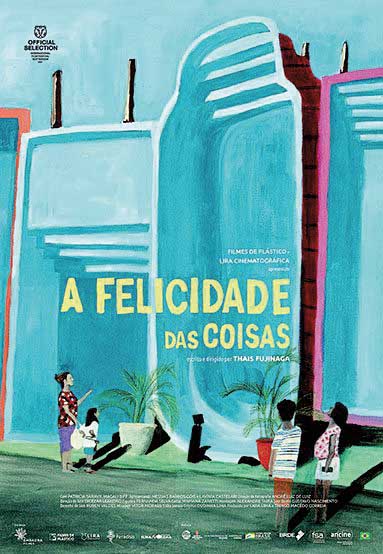

But sometimes common sense isn’t what people care about. In Brazilian director Thais Fujinaga’s debut feature, The Joy of Things, the relentless pursuit of a pool symbolizes one family’s desire to attain middle-class status—and a vision of happiness that seems ever more questionable.

Forty-year-old Paula is spending the summer with her mother and two children in Caraguatatuba, a coastal city to the east of São Paulo. Between scenes of idle and idyllic vacationing, we see a large ditch dug in the front yard. Nearby is a giant blue tank lying on its side, immobile. After indulging her kids’ wish for a pool, Paula has run out of money before it can be installed.

Preoccupation with the unfinished pool comes to dominate Paula’s life. She spends much of her time on the phone—with the man who sold her the tank, who threatens her over the sums she still owes him; and with her estranged husband, who won’t hold up his end of the bargain. Her obsession becomes so all-consuming that she fails to recognize her family’s changing attitudes. Her mother Antônia tries to be the voice of reason: “Soon that house is gonna start collapsing, and you’re worried about the pool. The pool is just one big headache.” But Paula won’t give up on the idea: “Up until yesterday, everybody wanted a pool. The pool was great.”

The Joy of Things (A felicidade das coisas)

Directed by Thais Fujinaga

Screenplay by Thais Fujinaga

Distributed by Filmes de Plástico and Lira Cinematográfica Brazil

Starring Patricia Saravy, Magali Biff, Messias Gois, and Lavinia Castelari

AQ Rating: 5/5

We see Paula’s stubbornness materialize in other ways, too. She frequently chastises Antônia for speaking with a fisherman who casts nets from a small patch of her yard next to a river. “This is private,” she chides him. “I bought it.” The fisherman is technically trespassing, but he’s hardly bothering anyone. His livelihood depends on access to the riverbank he has fished from for years—land that’s now partially owned by Paula. His sons are even friends with her own teenage son Gustavo. None of it matters: Paula’s fetishistic view of property clouds her judgment, isolating her from the people who matter most.

There’s a broader context for what the pool and the fisherman say about Paula’s fixation on status. In the early 2000s, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva instituted social policies that significantly reduced poverty in Brazil. His administration, as the sociologist Perry Anderson has argued, “took to boasting of its achievement as the creation of a ‘new middle class.’” Brazil’s previously poor were invited to identify with the “consumerist individualism” of the established middle class. As Fujinaga’s film suggests, their new wealth encouraged the same disdain for the lower classes that the country’s established elite has long cultivated. When commodity prices crashed in the early 2010s, so did the presumed stability of this “new middle class”—but not its newfound hopes and expectations.

The pool could be a metaphor for politics in Brazil—or many other Latin American countries, for that matter. Highways only partially built, hospitals in perpetual construction, neglected schools—the list of half-realized dreams, taken up during times of bounty and abandoned during times of want, goes on and on. The enormous gap between reality and aspiration raises the question: Why pursue these plans in the first place?

The Joy of Things is about the wreckage left behind by broken promises. Under the pretext of the swimming pool, Paula spends the vast majority of her time and energy away from her family. She’s almost as absent as her kids’ father, who never appears on screen. But even sadder and more ironic is that Paula’s family spends the summer on the coast: They hardly need a pool to begin with. Why bother with the hassle and expense when the ocean is right next door?

—

Alvarado is a writer and former assistant editor at The Atlantic.