SÃO PAULO – At a recent dinner party in São Paulo, a friend who is an executive at a technology company mentioned that he and his wife are planning to move to Lisbon. “The public schools in Portugal are great, it’s totally safe, and I can get almost all my work done remotely,” he said. He added that he expected to fly to São Paulo every month or two, whenever an in-person meeting would be necessary. Several other guests said they, too, were considering taking their families to Lisbon or Miami after having spent several months during the pandemic working from abroad. Indeed, the possibility of working remotely has spurred a debate about leaving Brazil among a growing number of Brazilian executives and entrepreneurs.

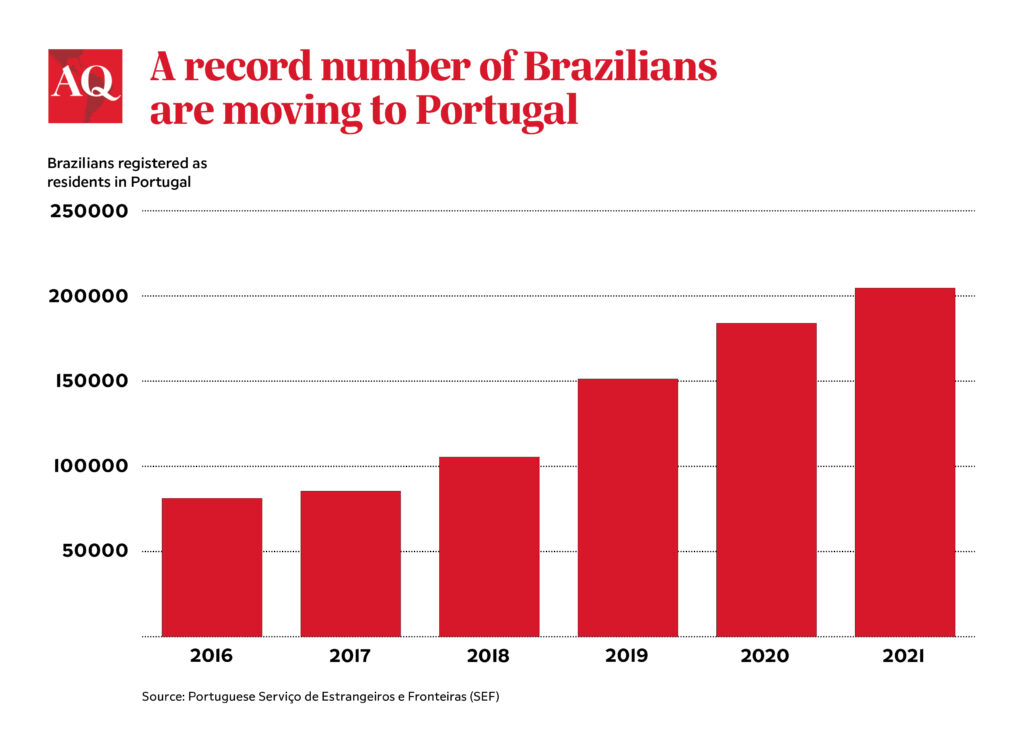

Such cases make up only a fraction of the increasing number of Brazilians who go abroad in search of opportunities. The bulk of those leaving the country are less privileged, though emigration is out of reach for the poorest. In 2021, a staggering 17% of Brazilians who traveled abroad did not return, a record high. The number of Brazilians legally residing in Portugal, for example, recently reached a new record of 252,000—a whopping 23% increase compared to last year. The actual number of Brazilians in Portugal is likely half a million, including those who live there illegally and the thousands of Brazilians who also hold European passports and thus do not register as Brazilians.

Moreover, the number of Brazilians applying for Portuguese citizenship also saw a significant increase over the past decade, from 24,000 in 2010 to 58,000 in 2020. Likewise, the number of Brazilians living in countries like Italy, Ireland and the U.S. has increased sharply over the past years—1.8 million Brazilians now live in the U.S., a 20% increase from 2016. The number of Brazilians detained at the US border is also reaching new records at nearly 150 per day.

Managers and entrepreneurs consider leaving not just for economic reasons—after all, many prefer to keep their high-end jobs in São Paulo or Rio, which pay much more than comparable opportunities in places like Lisbon. Often, they seek to offer their children “normal upbringings” with better safety and public education outside of the elite bubble. This reveals deep-seated doubts about whether Brazil can overcome its most urgent challenges, such as profound inequality and a lack of public safety, over the years to come. Few of the Brazilians born in the 1970s and 1980s now reaching the top echelons of their organizations or heading their own companies have much faith that anything remotely resembling the commodity boom-fueled optimism of the late Lula years will return anytime soon. It is often forgotten that at the time, migration flowed in the opposite direction; Brazil was attracting countless young professionals from countries like Portugal and Spain, and thousands of Brazilians were returning from abroad.

While negligible in terms of total numbers, the growing elite brain drain—already highly visible in the scientific community, where scholars face a dramatic shortage of research funds—is deeply troubling. Brazil has endured a decade of near-zero growth and desperately needs to boost per capita worker productivity to avoid falling behind and remaining subject to the wild swings of commodity prices that inevitably produce political instability at every downturn.

Brazil has seen economic crises before that produced emigration, but the current moment suggests a more permanent change. For example, the number of Brazilians pursuing their university undergraduate degrees abroad has risen sharply and now stands over 70,000. Of those who pursue undergraduate degrees outside of Brazil, many can be expected to initiate their professional careers abroad and are less likely to return. The departure of highly skilled professionals tends to produce ripple-effects across society; doctors, scientists and entrepreneurs take with them their networks, ideas and capacity to create jobs and pay taxes.

Elite emigration is also a major problem for the public sector and civil society, whose capacity to attract skilled professionals is an essential element of a functioning democracy. Worse still, emigration tends to encourage further emigration, since professionals who establish themselves abroad often identify job opportunities for their former colleagues back home. The decision by highly informed and well-connected individuals to leave is a worrisome indicator and may dampen the country’s long-term growth prospects.

Back in 2012, with cafés in Rio and São Paulo bustling with recently arrived professionals from abroad, few could have imagined that only ten years later, record numbers of Brazilians would leave. Perhaps Brazil is due for another unexpected turnaround, and its malaise will end sooner than many expect. For now, though, Brazil’s loss is the gain of countries like Portugal: Sensing an opportunity, the country recently decided that Brazilians—along with nationals from a number of other Portuguese-speaking countries—can live in Portugal for up to six months to search for a job.