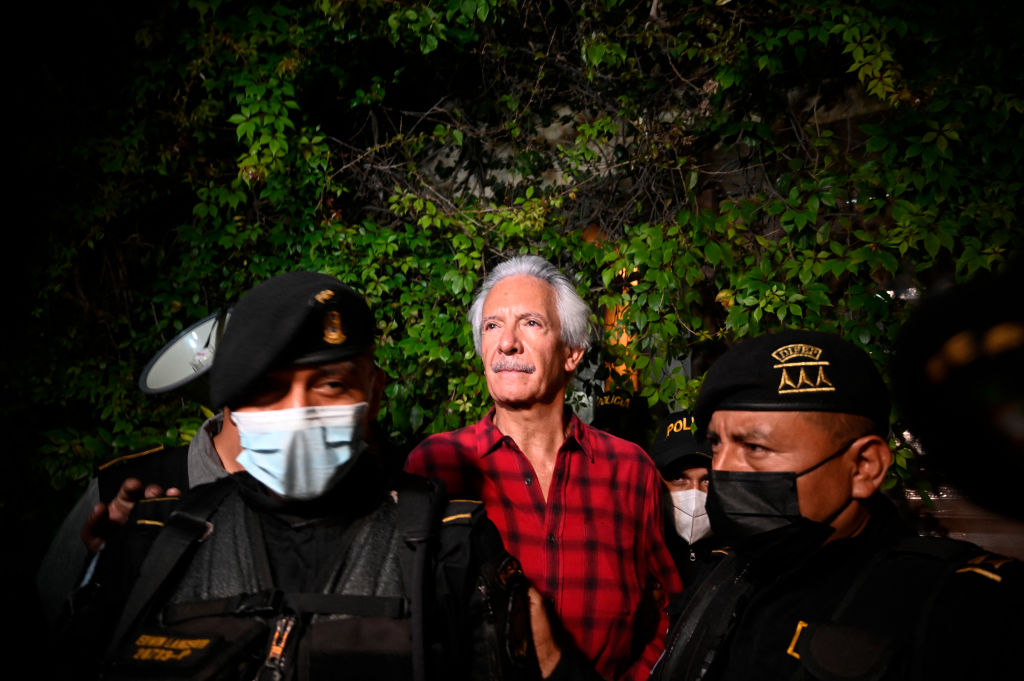

Masked police officers emerged from an unmarked convoy to arrest José Rubén Zamora, the director of the El Periódico newspaper, at his home in Guatemala City on the night of July 29. An internationally acclaimed journalist best described as a die-hard centrist, Zamora has been a thorn in the side of Guatemalan governments for over 30 years, enduring lawsuits, threats and physical assaults.

Now, he is in prison. Zamora’s unprecedented arrest has exposed Guatemala’s march toward autocracy and kleptocracy, as well as the costs of excessive U.S. and international caution in Central America.

The arrest is part of a broader effort to neutralize independent journalism as well as civil society and Indigenous organizations. It is also a signal that these trends are set to intensify, mirroring the paths taken by Nicaragua and Venezuela. Guatemalan journalists serve as a crucial check on corruption and abuses by those in power, just as their contemporaries in those two countries had before they were silenced.

The Attorney General’s Office accuses Zamora of money laundering and extortion, but it has offered no details other than to oppose bail. It said Zamora was arrested as a “businessman,” not a journalist, but it froze El Periódico’s bank account all the same.

No one in Guatemala suggests journalists should be above the law, but in today’s Guatemala, there is no independent judiciary to apply the law. The attorney general and the judges who are trying Zamora have no more independence from President Alejandro Giammattei than did the prosecutors and judges in Nicaragua who jailed President Daniel Ortega’s rivals in the 2021 “election”—or the Russian judge who just sentenced U.S. basketball star Brittney Griner.

Attorney General Consuelo Porras and anti-corruption prosecutor Rafael Curruchiche, who is prosecuting Zamora’s case, are both on the U.S. State Department’s Engel List of “corrupt and undemocratic actors”; they have allegedly sidelined major corruption investigations and driven two dozen anti-corruption prosecutors and judges into exile.

This is the result of pushback in the wake of Guatemala’s landmark anti-corruption prosecutions from 2015-18, assisted by the now-defunct Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), of prominent politicians and business leaders. Those in the crosshairs of the investigations supported first President Jimmy Morales (2017-21), and then his successor Giammattei, to ensure that such investigations would never happen again.

With the support of most of Guatemala’s economic and political elite, Giammattei engineered a stunning takeover of the judiciary. His administration won control of Congress by leveraging its flexible spending authority; its finger on the on/off button of corruption investigations; its control of the judiciary and electoral tribunal; and support from parties with alleged ties to drug traffickers.

Wealthy defendants in major corruption cases who had fled the authorities have now turned themselves in, and the attorney general is considering charges against some of the prosecutors who had tried them. The government enjoys the support or acquiescence of the country’s wealthiest families who have set the parameters of economic policy for the last 60 years and value Guatemala’s low tax burden—the lowest in the hemisphere save Haiti. They also fear that a more accountable government could lead to greater power and a greater share of resources for the poor and the Indigenous.

Guatemala’s economic elite had applauded Zamora’s earlier reporting on corruption during the populist Portillo and Colom governments. In recent years, however, independent investigative media such as El Periódico, La Hora and the radio show ConCriterio have struggled to attract private sector advertising dollars. Meanwhile, authorities have jailed Indigenous journalists outside the capital, others have received threats, and a lawsuit against investigative journalist Juan Luis Font forced him into exile.

The reason? Giammattei’s government and his allies’ success provided an environment for investigative reporting that can only be described as target-rich. In 2021, El Periódico and other outlets reported on irregularities in Guatemala’s unusual $80 million third-party procurement of Russian Sputnik vaccines, alleged Russian abuses surrounding the El Estor nickel mine, and accusations that the president had received illegal payments from Russian businessmen.

Giammattei has denied the allegations, and there seems to have been no comprehensive investigation into them. El Periódico has also investigated his close friends, interference in the justice system, and alleged connections between Giammattei allies and narcotraffickers.

Zamora’s arrest is in part a message for Giammattei’s wavering allies; Giammattei reportedly distrusts certain allies like Zury Ríos to protect his legal, political and financial interests after his term ends. (He is constitutionally barred from re-election.) Ríos is a potentially strong 2023 presidential candidate and the daughter of former President General Efraín Ríos Montt (1982-83), convicted in Guatemalan court of ordering acts of genocide. (The conviction was later overturned.) Giammattei reportedly prefers Manuel Conde, a Giammattei loyalist who has a much lower profile.

He is understandably concerned about his post-presidency fate. He is extremely unpopular, even more so than Daniel Ortega or Nicolás Maduro, and unbridled corruption has led to so much abuse, incompetence and indifference to citizens’ needs that it will continue to dominate public discourse. Zury Ríos herself, despite her alliance with Giammattei, has staked out a position against corruption that distances her somewhat from the current government. Moreover, citizens may at some point take to the streets as they did in 2015 when they forced then-President Otto Pérez Molina to resign. (He remains in prison on corruption charges.)

But Zamora’s arrest also sends a powerful message to the international community: Guatemala’s powerbrokers are unafraid to violate democratic norms and will not allow an independent judiciary. They have therefore ignored high-level U.S. encouragement—during Vice President Kamala Harris’ June 2021 visit, for example—to support the rule of law.

The U.S. is Guatemala’s most important economic partner outside Central America, and Guatemala’s stability relies upon migration to the U.S.—both as a pressure-relief valve for people trapped in an economy that caters to the wealthiest and for the $1.5 billion in remittances that Guatemalans send home every month.

Despite this apparent U.S. leverage, however, Giammattei has judged—correctly, so far—that the U.S. predisposition to caution and its excessively short-term focus in Central America give him the upper hand.

Giammattei’s leverage is in large part Guatemala’s cooperation on migration, a sensitive U.S. election issue. Guatemala continues to detain some foreign migrants bound for the U.S. and to accept the return of 50,000 to 100,000 migrants from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador each year. (This figure is dwarfed by the 200,000 to 300,000 Guatemalans who migrate annually to the U.S.)

Giammattei has also continued Guatemala’s traditional support for Israel and Taiwan, and he has supported Ukraine against Russia (albeit without transparency on reported Russian business actions in Guatemala).

He likely believes the U.S. is reluctant to use tougher trade or Treasury sanctions under the Magnitsky Act out of fear that Giammattei will withdraw cooperation, especially on migration.

Excessive caution can be dangerous in its own way. In the long run, short-term, “play-it-safe” policies toward Central America will only guarantee greater instability, disruption and migration.

The international community cannot impose democracy, rule or law, or transparency on a foreign country—only a country’s own citizens can do that. It can, however, use sanctions to penalize certain behaviors that favor dictatorship and organized crime, and it can use its voice to support victims of abuse.

The broad U.S. application of Magnitsky Act human rights and corruption sanctions to Guatemala would be an excellent start. Multilateral trade sanctions on certain industries should also be prepared.

The U.S. could review the compliance of ports and banks with U.S. law; ratchet up its use of Engel List visa cancellations; and ensure that its intelligence and law enforcement agencies are dedicating appropriate resources to Central America.

Time is no longer on the side of the U.S. and of those who support democracy. Zamora’s arrest was a harsh reminder that time is running out to support democracy in Guatemala, and in much of the rest of Central America.

—

McFarland (@AmbMcFarland) is a retired Foreign Service officer who was the U.S. ambassador to Guatemala from 2008-11. Earlier he served twice in Venezuela, and in El Salvador and Peru during their internal conflicts. His career has focused on the Andean countries and Central America, in addition to Iraq and Afghanistan.